The history of North America brims with tales of resistance and resilience, particularly from its indigenous cultures, among which the Ojibwe people hold a distinct place. In 1763, the Ojibwe, also known as Chippewa, confronted British colonial intrusion with an audacious uprising at Michilimackinac. This event was not merely a historical footnote but a critical juncture highlighting indigenous agency against colonial encroachments. Through a deep dive into this significant episode, we can unravel the dynamics of power, strategy, and resistance that shaped the region’s socio-political fabric.

Featured Image – Fort Michilimackinac – WMrapids, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Situating the Ojibwe Identity and Historical Context

Situated within the broad spectrum of North American indigenous cultures, the Ojibwe people, also known as Chippewa, have maintained a rich, enduring history shaped by their unique customs, beliefs, and tenacious spirit. This multifaceted culture faced significant disruption in 1763 due to British colonial intrusion—an era-defining episode worthy of deeper exploration.

Unraveling the Roots of Colonial Discord

The Ojibwe’s sociopolitical landscape in the mid-18th century was a cauldron simmering with tension, poised on the brink of rebellion. The encroachment of British colonizers upon Ojibwe territories ignited a smoldering fire of discontent. British authorities disregarded Ojibwe sovereignty, usurping their lands and disrupting time-honored ways of life—a provocation that precipitated significant retaliatory actions.

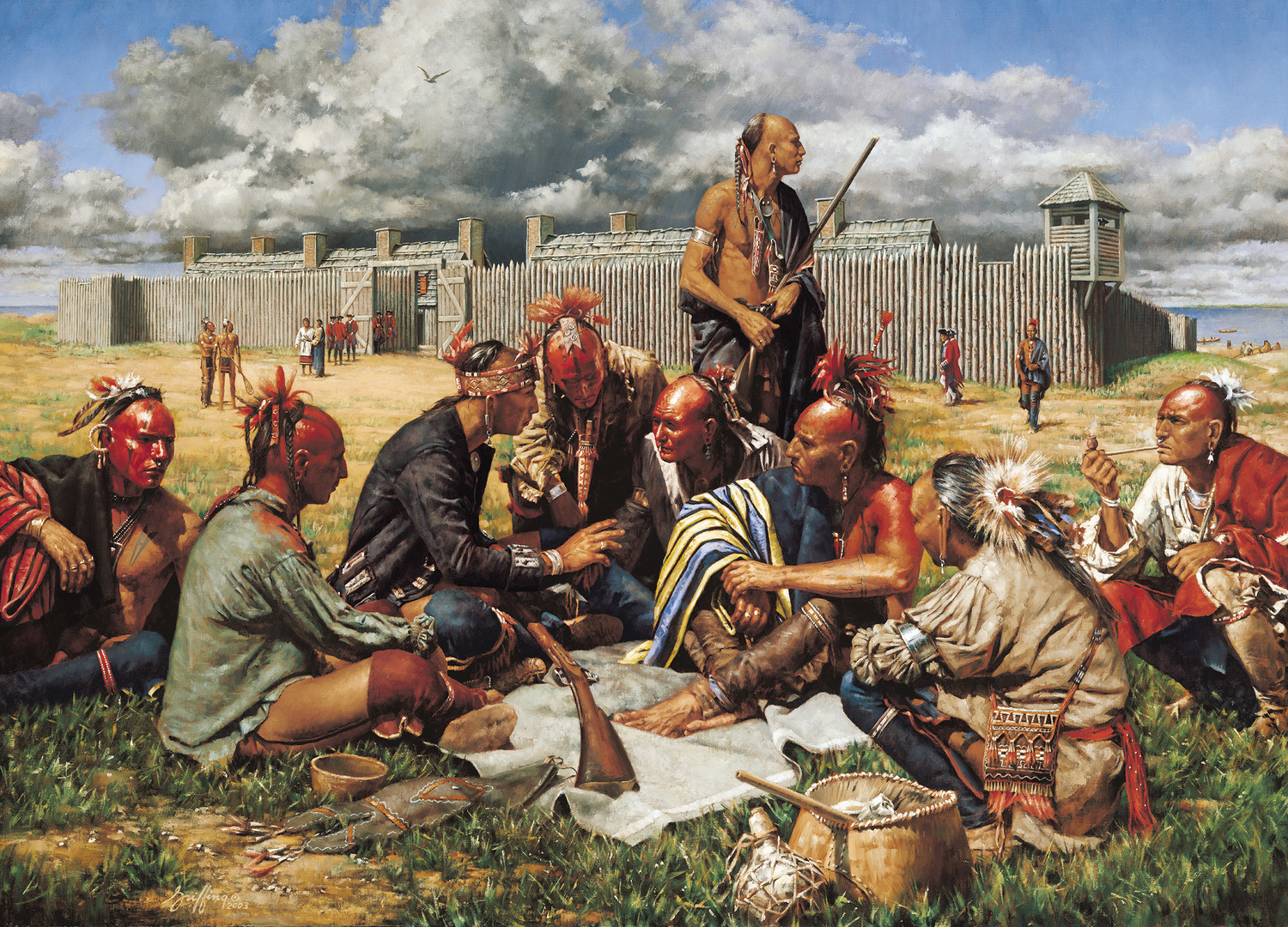

Protagonists of the Rebellion: A Tapestry of Leaders

At the center of this political maelstrom were stalwart Ojibwe war leaders Minavavana and Matchekewis. Affiliated with the renowned Odawa Chief Pontiac, these individuals exhibited strategic acumen and unwavering resilience in responding to colonial oppression. On the other side stood Alexander Henry, a British fur trader, and Major George Etherington, commandant of Fort Michilimackinac—both of whom would bear witness to the forthcoming historical watershed.

Breaking of Treaties Sparks A Movement

The Indians were unhappy with British policies, especially those relating to trade, as gifts were eliminated and trade was restricted after the French and Indian War. This dissatisfaction and the misplaced hope that the French would back them set the stage for a rebellion. This led to a coalition of Native Americans from Canada to the Mississippi Valley, who waged Pontiac’s War. As a result, British soldiers and merchants had to withdraw from most of the posts beyond the Allegheny Mountains in just a few months.

In early May, the Ottawa chief Pontiac and his followers laid siege to Fort Detroit. During the Spring of 1763, a plan was developed also to capture Michilimackinac which is located on the strategic Straits of Mackinac . Pontiac is also widely believed to have orchestrated the attacks on other British forts in the Great Lakes region.

The Ingenious Strategy: Baggataway and Subterfuge

In an elaborate dance of warfare strategy and cultural preservation, the Ojibwe invoked the traditional game of baggataway, a precursor to modern lacrosse, to conceive an ingenious attack plan. A feigned celebration of King George III’s birthday served as the façade under which they executed this strategy. The audacious subterfuge brilliantly exploited the element of surprise, thereby destabilizing the British military stronghold.

The Michilimackinac Uprising: A Clash of Cultures

June 2, 1763, witnessed a meticulous execution of this calculated rebellion. As the baggataway ball soared over the fort’s gate, the Ojibwe players transitioned seamlessly from athletes to warriors, unsheathing weapons surreptitiously supplied by the women of their tribe. Within moments, Fort Michilimackinac was plunged into chaos, with Etherington and his Lieutenant Leslie whisked away as the solitary armed officer, Lieutenant James, fell in the melee.

From the shadows of his hideout, Alexander Henry, concealed by a Panis slave girl, observed the chilling spectacle. His accounts lend evidence to a striking anomaly—the Ojibwe were exclusively targeting the English, sparing French Canadians—an intriguing wrinkle in the tapestry of the attack.

Post-attack Dynamics: Immediate Repercussions and Long-term Impact

Following the fort’s capture, the captives’ proposed transport to Beaver Island was intercepted by the Odawa. The Odawa, feeling slighted by their exclusion from the assault, seized control of the captives and the fort. An unexpected kinship between Henry and an Ojibwe named Wawatam, who claimed a spiritual vision had prompted him to adopt an Englishman, ensured Henry’s survival.

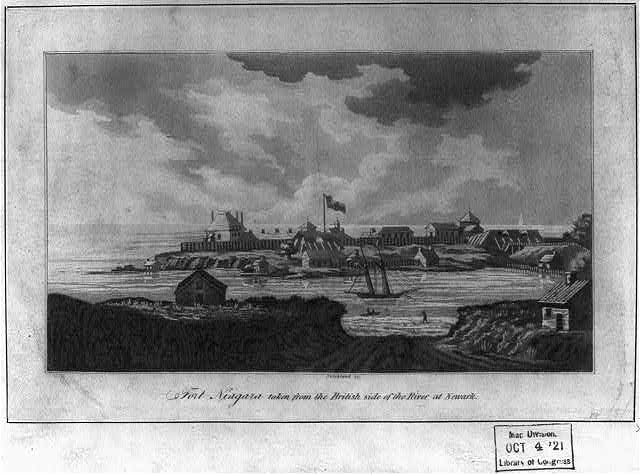

The consequences of the Michilimackinac attack reverberated far beyond the immediate tactical victory. The British response was swift, as they mobilized 3,000 soldiers from Fort Niagara to Fort Detroit to confront Pontiac and his tribes.

The Ojibwe’s audacious revolt dramatically reshaped the power dynamics within the region, inducing strategic shifts in British colonial policy. Although the British ultimately regained control, they were compelled to acknowledge indigenous rights with increased seriousness—a paradigm shift in colonial-indigenous relationships. This seminal event underscores the broader implications of indigenous resistance in shaping colonial attitudes and policies.

Reflections on Historical Significance and Contemporary Legacy

The Michilimackinac attack offers more than an isolated historical snapshot; it provides a crucial lens to reflect upon Ojibwe’s active agency and resistance. It signifies an indigenous people’s refusal to be passive victims of colonial expansion and underscores their ability to leverage cultural elements in tactical maneuvering. The actions of Minavavana and Matchekewis have become emblematic of indigenous resistance to colonial rule, symbolizing courage, ingenuity, and an indomitable spirit.

In contemporary Ojibwe communities and wider society, their legacy remains manifest. Today, we witness a resurgence of indigenous cultures, a testament to their unyielding resilience. This resurgence, embedded in cultural revival and political assertion, echoes the spirits of Minavavana and Matchekewis—unforgotten heroes in the annals of Ojibwe and indigenous resistance.

Acknowledging Sources

This exploration into Ojibwe history and the Michilimackinac uprising has been made possible through the meticulous research and insights provided by numerous sources. These include…

June 2, 1763 – Pontiac’s Rebellion – On June 2, 1763, Pontiac, a leader of the Ottawa tribe, led an uprising against British forces in the Great Lakes region. The uprising, known as Pontiac’s Rebellion, lasted for nearly a year and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of British soldiers and civilians. The rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, but it did force the British to change their policies towards Native Americans.

Deadly Lacrosse Game in Mackinac Straits at Fort Michilimackinac in 1763 – On June 2, 1763, a group of Native Americans invited the British soldiers at Fort Michilimackinac to watch a game of lacrosse. When the soldiers left their weapons inside the fort and gathered outside to watch, the Native Americans attacked, killing most of the soldiers and taking the rest prisoner. This event, known as the “Deadly Lacrosse Game,” was one of the first attacks in Pontiac’s Rebellion, a widespread uprising of Native Americans against British rule in North America.

Life and Death at Fort Michilimackinac – Richard Beringer will give a presentation at the Romeo District Library about life and death at Fort Michilimackinac in the 1700s. The presentation will focus on the events leading up to and including the Deadly Lacrosse Game, a surprise attack by Native Americans on British soldiers at Fort Michilimackinac on June 2, 1763. The attack was part of Pontiac’s Rebellion, a widespread uprising of Native Americans against British rule in North America.

By understanding the past, we can better navigate our collective future. The tale of the Ojibwe’s resistance underscores the timeless relevance of respect for all cultures and territories—a lesson we’d do well to remember as we share our world.