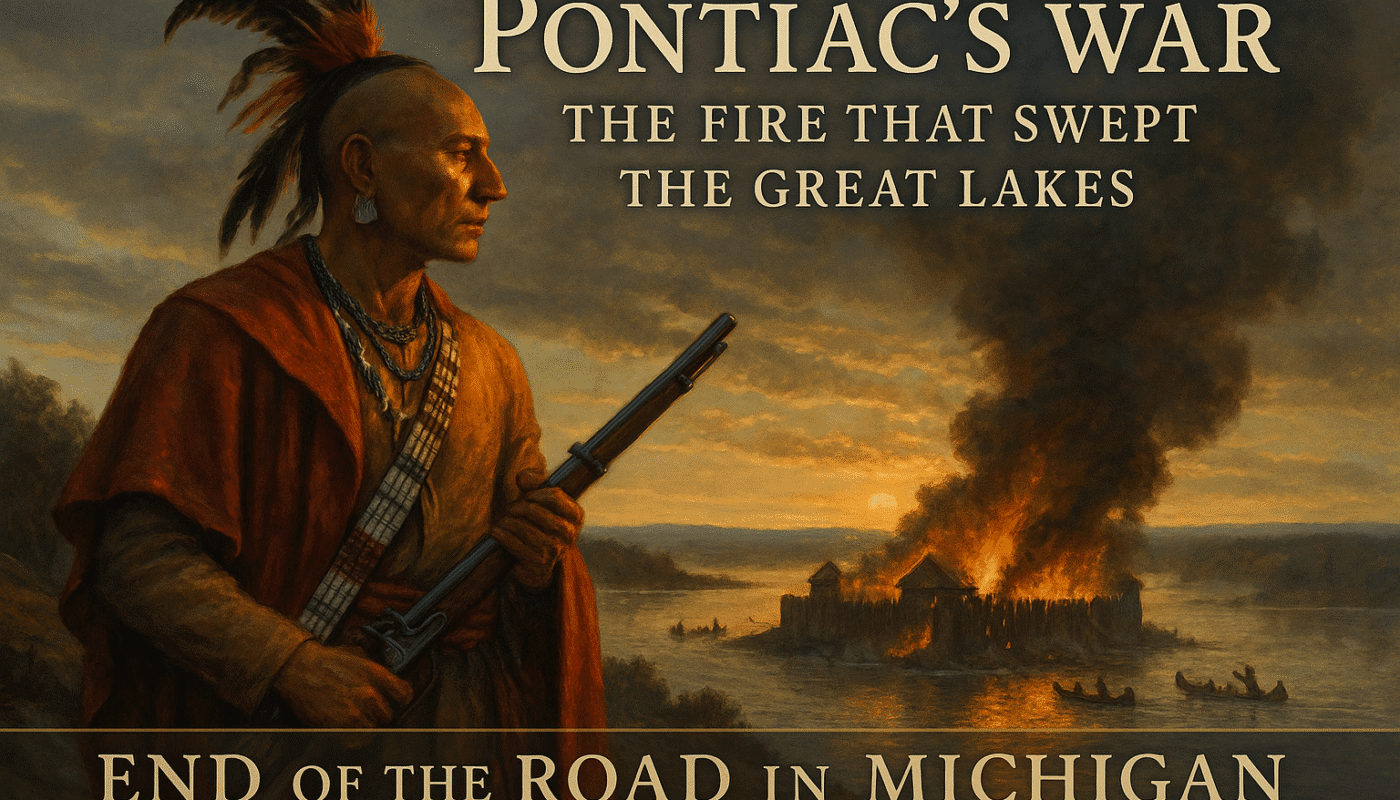

Pontiac’s War (1763–1766) was a coordinated Indigenous campaign to force policy changes after Britain took former French lands. In the Great Lakes, Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Wyandot, and allies overran small British posts, held Detroit under siege for months, and seized Fort Michilimackinac using a staged lacrosse game. The fighting and costs pushed London to issue the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which halted settler expansion on paper and restored diplomatic practices the British had cut.

The Aftermath of the Seven Years War

Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War left Native nations dealing with new officials who ended gift-giving and restricted trade in powder and lead. Settlers moved toward the Ohio Country as garrisons took over French posts. Many Indigenous leaders saw an existential threat. The Delaware prophet Neolin urged spiritual renewal and unity. His message and rising pressure set the stage for war.

Indigenous Leadership and Aims

Pontiac, an Odawa war chief from the Detroit region, helped coordinate action among neighboring nations. His role was important but not singular; local leaders rose across the region. Guyasuta (Seneca/Mingo) was central near Fort Pitt. The goal was clear: force the British east of the Appalachians and restore fair trade and diplomacy, not conquer colonies outright.

Timeline of Key Events (1763–1765)

- April 27, 1763 — Council near Detroit: Leaders agree on coordinated strikes.

- May 7, 1763 — Fort Detroit: A planned surprise entry fails; a five-month siege follows.

- May–June 1763 — Outposts fall: Sandusky, St. Joseph, Miami, Ouiatenon, Venango, Le Boeuf, Presque Isle are taken; garrisons are killed or captured.

- June 2, 1763 — Fort Michilimackinac: Ojibwe players use a lacrosse match as a ruse to storm the fort; the post falls the same day.

- June–July 1763 — Fort Pitt siege: British officers discussed—and at least attempted—the use of smallpox-infected items against emissaries; disease was already present, and the exact effect remains debated.

- Aug. 5–6, 1763 — Battle of Bushy Run: Col. Henry Bouquet breaks the attacks and reopens the route to Fort Pitt.

- Oct. 7, 1763 — Royal Proclamation: Crown bars settlement west of the Appalachians and formalizes controlled land purchases.

- 1764 — British expeditions: Bradstreet on the lakes; Bouquet into the Ohio Country secures releases of captives and peace terms.

- July 1765 — Detroit peace council: Hostilities wind down in the Great Lakes.

- July 1766 — Oswego: Pontiac signs a formal peace with Sir William Johnson.

Major actions and tactics

Indigenous forces struck many posts at once, isolating the big forts. At Detroit, hundreds of Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Wyandot fighters cut supply lines and ambushed relief columns. The Battle of Bloody Run near Detroit cost the British heavily, but the fort held.

At Michilimackinac, Ojibwe players retrieved a ball “hit” through the gate while women inside passed in weapons; the swift attack overwhelmed the small garrison.

Near Fort Pitt, raids and a siege strained both sides until Bushy Run, where a feigned retreat by Bouquet broke the assault.

British responses and policy shifts

Initial policy was punitive under Gen. Jeffery Amherst, who had ended gift-giving and restricted trade. By late 1763, Amherst was replaced. The Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, drawing a line at the Appalachians, recognizing Indigenous control west of that boundary, and restoring diplomatic practice with gifts and regulated trade. Enforcement lagged as settlers defied the line, but the policy change was direct fallout from the war.

Outcomes

- No clear battlefield victor. The alliance did not take Detroit or Pitt, yet British counter-moves ended with negotiations and policy reversals rather than decisive conquest.

- Short-term aims met. London restored trade and diplomacy and paused western settlement on paper.

- Human costs. Hundreds of civilians died in frontier violence; military deaths mounted on both sides; smallpox outbreaks struck Native communities. Numbers vary by source; cautious phrasing is warranted.

- Foreshadowing. The Proclamation angered land-hungry colonists and fed disputes that helped set the stage for the American Revolution.

Legacy and memory

For many Native communities, this was a justified defense of homelands. The campaign showed that a pan-tribal coalition could compel an empire to change course. Later confederacies—Blue Jacket and Little Turtle in the 1790s, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa in 1811—echoed lessons from 1763. Sites at Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Mackinac interpret the conflict today with broader perspectives than earlier narratives.

Images on this page may contain affiliate links in which we may receive a commission. See our affiliate disclosure for details.

Historic Photos of Detroit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s

Historic Photos of Detroit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s documents what a Metro Detroiter would have experienced through those decades, from the commonplace—to a visit from John F. Kennedy.

FAQs – Pontiac’s War in Michigan

Was Pontiac the sole commander?

No. He was a crucial organizer around Detroit, but many leaders acted independently across the region.

Did smallpox blankets decide the siege of Fort Pitt?

British officers discussed and attempted to spread smallpox via items given during a parley. Disease was present in the region already; historians debate the specific impact. The siege ended after the British victory at Bushy Run.

What changed after the war?

Britain restored gift-giving and regulated trade and drew the Proclamation Line to limit settlement. Enforcement was weak, but the policy shift was significant.

Works Cited

Dowd, Gregory Evans. War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and the British Empire. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Middleton, Richard. Pontiac’s War: Its Causes, Course and Consequences. Routledge, 2007.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

“Royal Proclamation, 1763.” Avalon Project, Yale Law School. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/proc1763.asp.

“Battle of Bushy Run.” Bushy Run Battlefield (Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission). https://bushyrunbattlefield.com/history/.

“Pontiac’s Rebellion.” Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/pontiacs-rebellion/.

“Fort Michilimackinac and the 1763 Attack.” Mackinac State Historic Parks. https://www.mackinacparks.com/blog/fort-michilimackinac-and-the-1763-attack/.

“Jeffery Amherst and Smallpox.” University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://www.umass.edu/legal/derrico/amherst/lord_jeff.html.

“The Indians delivering up the English Captives to Col. Bouquet, Nov. 1764.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003689185/.

“Pontiac’s Rebellion.” American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/pontiacs-rebellion.