Mio, Michigan is a small town with a big story. Tucked in the forests of Oscoda County, Mio’s history spans boom, bust, and revival – all centered on its natural resources. For anyone researching Mio Michigan history, the town offers a classic case of a 19th-century logging settlement that reinvented itself in the 20th century as a hub for hunting tourism, conservation efforts, and small industries. This article explores Mio’s journey from lumber camps to a modern outdoor getaway, highlighting key events, economic shifts, and cultural changes that shaped its identity. (Mio Michigan history in focus.)

Video –

Lumbering Roots in the 19th Century

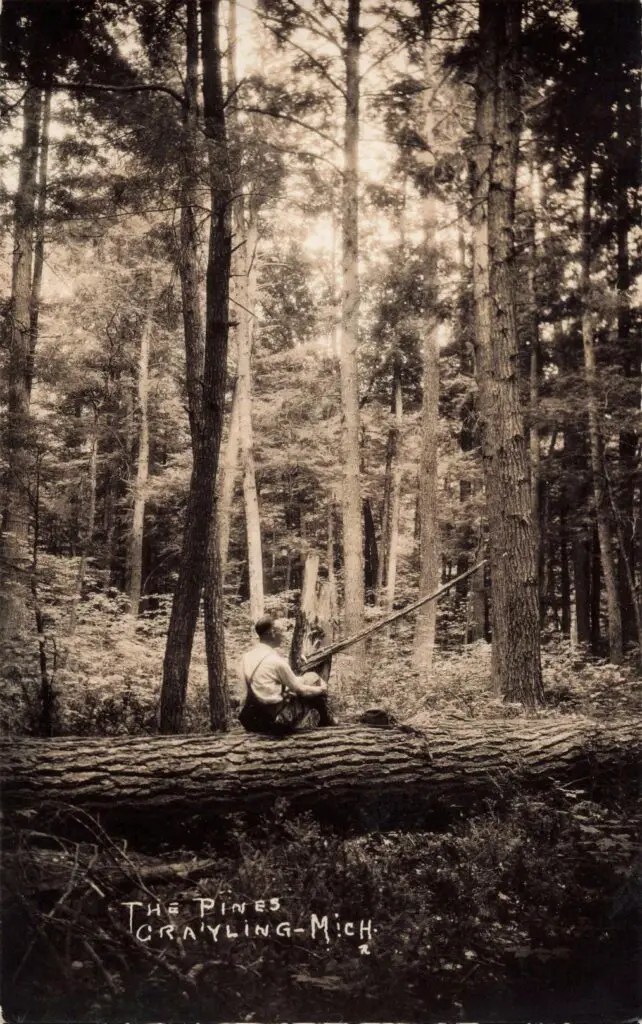

Mio’s story begins in the late 1800s, when Michigan’s great white pine forests were being feverishly logged. The community was founded in 1881 (initially named “Mioe” for a founder’s wife) during the lumber boom. At that time, logging was king. Oscoda County’s dense woodlands attracted timber companies and sawmill operators. Mio and nearby camps like McKinley thrived on the logging business. Historical records note that McKinley – nicknamed Pott’s Headquarters – became the center of the county’s lumber industry, complete with narrow-gauge railroads stretching deep into the woods. In those days, most transportation was by river: logs and even railroad equipment were floated down the Au Sable River to reach markets.

By the 1890s, Mio boasted sawmills, boarding houses, saloons, and a steady influx of lumberjacks. The population swelled seasonally, and the local economy revolved around timber. However, like many Michigan lumber towns, Mio’s boom was short-lived. The timber was harvested relentlessly, and by the early 20th century, the great pine stands were depleted. The bust came swiftly – sawmills closed and jobs vanished as loggers moved on to untouched forests elsewhere. A telling milestone was the closure of the local rail line: the last train left Oscoda County in 1928 when the railroad, no longer profitable without lumber freight, shut down. What remained was a landscape of cutover stumps and a much quieter town.

From Desolation to Conservation

After the logging era, Mio faced the challenge of adapting or disappearing. The early 1900s saw attempts to farm the cleared land. Notably, in 1900 a community of Amish settlers arrived, attracted by the inexpensive cutover acreage. They planted crops on former timberland and helped maintain a rural economy as the forests slowly started to regrow. Meanwhile, Michigan’s state and federal authorities recognized that the region’s deforestation needed remedy.

In 1909, the U.S. Forest Service established the Huron National Forest around Mio. Its mission: to manage and replant areas left barren by logging. Over subsequent decades, this effort (aided by programs like the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s) transformed Mio’s environment. Large portions of Oscoda County were replanted with pine seedlings or allowed to regenerate naturally. Conservation wasn’t just about trees; it also became crucial for wildlife. The area’s fauna rebounded as habitats were restored.

By the 1930s, residents noted growing populations of white-tailed deer and black bears in the recovering forests. Even more significant was the discovery that Mio’s vicinity was prime habitat for the Kirtland’s warbler, a rare songbird. The first Kirtland’s warbler nest was found in Oscoda County in 1903. This bird requires young jack pine forests – exactly the kind of ecosystem being managed around Mio. In the mid-20th century, conservationists launched efforts to protect the warbler.

By 1958, core habitat areas in Oscoda and neighboring counties were set aside and managed for the species’ survival. These efforts eventually paid off, and today the Kirtland’s warbler is a conservation success story linked closely to the Mio area. Thus, the mid-20th century saw Mio shift from exploiting natural resources to restoring and conserving them.

Mid-20th Century: Hunting, Fishing and “Up North” Tourism

As the forests grew back, so did opportunities for recreation. By the 1940s and 1950s, Mio had gained a reputation as an “up north” destination for people from Michigan’s cities. Instead of lumber, the new draw was outdoor tourism. Hunting became especially central. Oscoda County’s regenerated woodlands and managed wildlife populations offered excellent deer hunting. Every November during Michigan’s deer season, Mio would see an influx of hunters (often from the Detroit area and southern Michigan) establishing camps in the woods.

The seasonal economy received a boost from these visitors buying supplies, lodging, and meals in town. Fishing was another attraction. The Au Sable River, no longer clogged with logs, became famous for its crystal-clear water and fish. Anglers came in search of trout, and Mio benefited from this clientele. A state fish hatchery upstream and fishing contests (like the Mio Pond Fishing Tournament for bass and pike.) underscored the area’s reputation. By mid-century, Mio was firmly part of Michigan’s outdoor recreation circuit, frequently mentioned as a prime spot for camping, canoeing on the Au Sable, and wildlife watching.

The local culture adapted accordingly. Businesses in Mio started branding themselves around the wilderness theme. A prime example was the Brooks Log Cabin Inn (sometimes called the Log Cabin Hotel). This establishment became known as the “Sportsmen’s Headquarters” in Mio – a rustic log building where hunters and fishermen gathered. It featured motel rooms, a hearty restaurant, and even a gas station to refuel both cars and patrons. The Log Cabin Inn was emblematic of Mio’s new identity: it wasn’t fancy, but it was friendly and catered to those looking for a Northwoods experience. (The Inn operated for decades until a fire in 1975 ended its run, illustrating how long the hunting tourism era lasted.)

Alongside the private sector, the government presence in Mio also grew to support outdoor activities. The Michigan Department of Conservation (precursor to today’s DNR) maintained a field office in Mio – one vintage photo from the 1940s shows the Conservation Department building in town, complete with official trucks. This reflects Mio’s role as a base for managing nearby state lands, forests, and game. In short, by the mid-20th century, Mio’s economy had shifted from cutting trees to catering to those who wanted to play among the trees.

Mio Michigan History – Community Initiatives and Small Industries

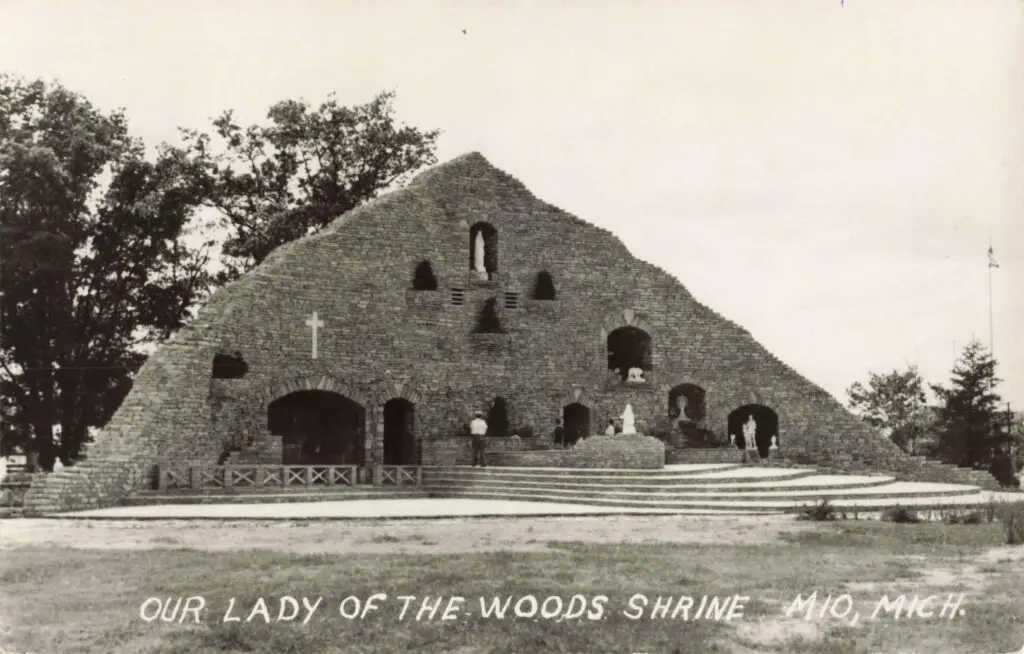

During this period of tourism growth, Mio’s residents also took initiatives to enrich their community and diversify the local economy. A standout project was the creation of the Our Lady of the Woods Shrine in the 1950s. This towering outdoor shrine, made of native stone, was built on the grounds of St. Mary Catholic Church in Mio. It began as a vision in 1945 by Father Hubert Rakowski, who prayed to improve the community and attract visitors. By 1953, local business owners were actively supporting the project, seeing its potential to draw tourists and pilgrims. Volunteers from all faiths helped build the shrine, hauling 25,000 tons of fieldstone to create a monumental curved wall 35 feet tall.

When it was dedicated on September 4, 1955, an estimated 4,000–5,000 people attended the ceremony – an extraordinary number given Mio’s small size. Newspapers and radio covered the event, and the shrine quickly became a regional attraction. For years afterwards, tour buses and travelers stopped in Mio to see the shrine, especially in summer. This blend of faith and tourism provided Mio with a unique cultural landmark (and it remains a maintained site to this day).

On the industrial side, Mio never attracted large factories, but it did see the rise of small businesses tailored to local skills and needs. The previously mentioned Perma-Log Company is a prime example of a home-grown industry. Founded around 1940 by Wellington “Bill” Maier, Perma-Log produced concrete log siding – an innovative building material. Maier, originally a plasterer from Detroit, invented a way to mold concrete into the shape of rustic logs and apply it as maintenance-free siding. He moved the operation to Mio, likely because the area’s rustic log cabin aesthetic fit the product.

The Perma-Log headquarters itself was a showcase: the office and Maier’s own house in Mio were covered in these faux logs, indistinguishable from real wood at a glance. The company’s slogan advertised the siding as a way to have a log cabin “that lasts a lifetime”. This small industry provided local jobs and added another facet to Mio’s economy. It’s noteworthy that Perma-Log became a multi-generational family business, indicating its lasting impact. Other modest enterprises in Mio included sawmills processing second-growth timber, craft workshops (wood carvings, hunting gear), and service businesses for tourists. Each contributed to Mio’s resilience as a community.

Legacy and Later Developments Of Mio Michigan History

The historical trajectory of Mio, Michigan demonstrates a resilient adaptation to changing times. By the late 20th century, the once-devastated forests around Mio were largely restored, thanks to sustained conservation and natural regrowth. This natural rebound enabled the town to flourish as a center for outdoor recreation. In addition, Mio’s role as the Oscoda County seat (a status it secured due to its central location back in the 1880s) ensured that certain civic functions and jobs remained in town, providing stability beyond tourism seasons.

Events in more recent history have tested Mio but also highlighted its community spirit. A notable incident was the 1973 PBB contamination crisis, when a chemical mix-up led to toxic flame retardant contaminating cattle feed statewide. Oscoda County farms were among the hardest hit, and some contaminated cattle were buried in a pit in Mio. The community weathered this agricultural disaster, which later led to improved safety regulations.

In 1985, Mio was in headlines again for a darker reason – the disappearance and murder of two hunters near town. The case remained unsolved for almost 18 years until convictions in 2003 brought closure. While tragic, it underscored that Mio had become a well-known gathering point for hunters (the victims were from metropolitan Detroit, up in Mio for deer season).

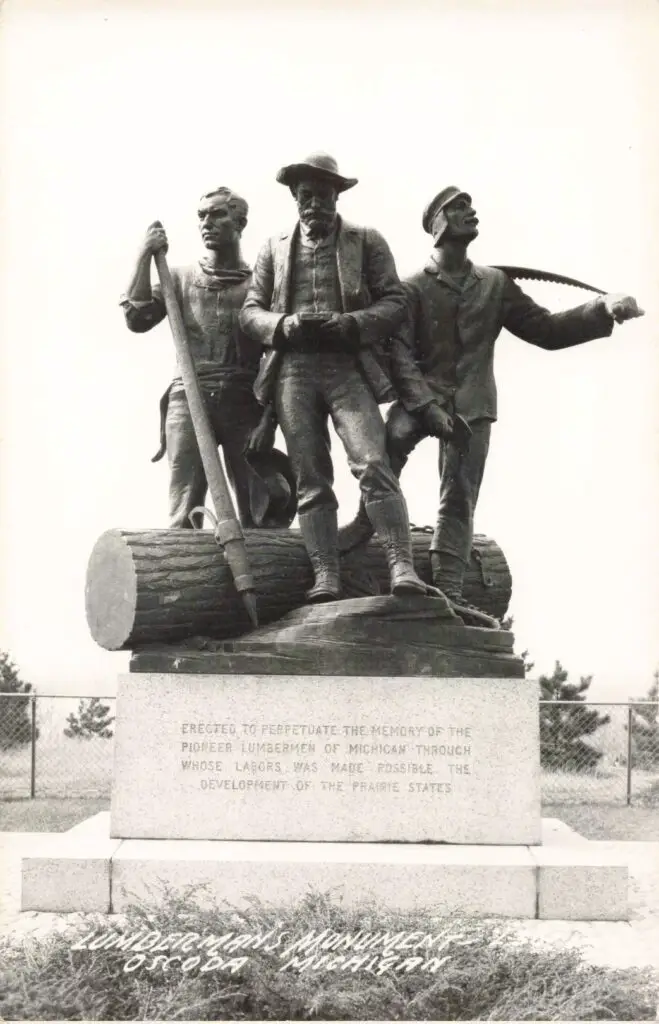

Through all these challenges, locals have remained proud of Mio’s heritage. The Oscoda County Courthouse, an icon built in 1888, stood in Mio for over 125 years until a fire in 2016. It has since been rebuilt, symbolizing the town’s determination to keep moving forward while honoring the past. Today, the Mio Michigan history of logging and renewal is remembered and celebrated. Visitors can stop by the Lumberman’s Monument (erected in 1932 near the Au Sable River downstream) which commemorates the loggers of old, or attend the Oscoda County Fair & Forestry Exposition, which highlights both farming and forestry.

Modern Mio offers a mix of experiences: canoe races on the Au Sable, warbler-watching tours in the jack pine plains, and quiet walks through forests that were once barren. The town’s journey from a 19th-century logging outpost to a 20th-century tourism and conservation center is a powerful example of how communities can transform their economies and identities.

Final Thoughts About Mio Michigan History

Mio, Michigan’s history is a microcosm of Michigan’s north woods experience – the rise and fall of logging, the hard times that followed, and the eventual rebirth through nature and community effort. This resilient little town managed to turn a devastated landscape into a thriving environment for both people and wildlife. From the rough days of lumber camps to the cheerful buzz of hunting season and summer vacationers, Mio has continually adapted.

Its story is preserved in the vintage postcards of dams, bears, and log cabins, and it lives on in the conservation successes and cultural landmarks like the Our Lady of the Woods Shrine. Mio Michigan history is still being written, but one thing is clear: the legacy of this town is one of renewal and hope amid the great forests of the Wolverine State.