In 1898, the first urban convention of civil engineers and architects was held in NYC. The topics were the value of open spaces and architecture in great cities, but the meeting stayed within the manure crisis of 1894.

What We Will Cover

Professional Urban Planners Try To Solve A Crappy Issue

The first urban convention of civil engineers and architects was held in New York City in 1898. It was organized by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) and the American Institute of Architects (AIA). The convention’s goal was to discuss the problems and challenges facing major cities at the time and explore possible solutions.

The convention focused on two main topics: the value of open spaces and architecture in great cities and the manure crisis. The attendees included prominent engineers, architects, and other experts from across the country, and they discussed a wide range of issues related to urban planning, design, and infrastructure.

The Manure Crisis of 1894

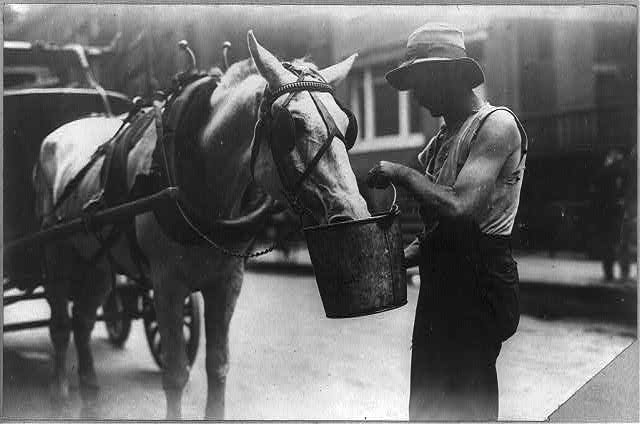

In the late 1800s, there were over 300,000 horses in NYC alone, generating 2 million pounds of manure and 60,000 gallons of horse urine daily. Every. Single Day. Times Square was initially called “Longacre” and a massive field owned by John Astor where he sold horses; not soon after the meeting, Astor sold it to the New York Times, and it became Times Square. (He later died on the Titanic.)

There were even entire city blocks where manure was piled nearly 100 feet high because the city could not deal with it. When it rained, the towns were filled with disgusting mud of excrement and filth. Pedestrians paid urchins to make a path before them as they walked. In some streets, the manure came up beyond the ankles; it was one reason there were steps up to the front doors of homes, and the “mud room” was where people removed their boots before entering the house to not track in filth—the NY Times reported that 3 billion flies were bred in the dirt every day.

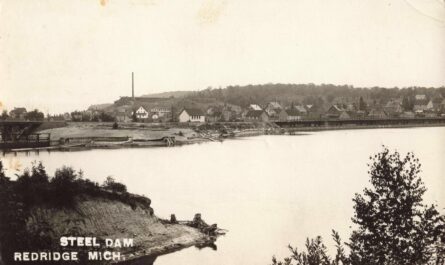

In earlier times, manure was sold by the city for a profit to farmers who carried it to their farms in dung carts; most of Brooklyn was still an open field in the mid-1800s. Then it was barged up north on the rivers to the farms. But as the city grew, the amount of manure increased beyond management, and by 10 AM, it was no longer suitable for manure because so much filth was mixed with the dung that it was unusable as fertilizer.

To make matters worse, the sanitation department was controlled by the Tamanny Organization, the biggest organized crime ring in America, and used for “no-show” patronage jobs. Streets could be cleaned by extortion only. More prosperous city dwellers had to pay off the sanitation department to clean the streets twice weekly. And the din of horses clopping was maddening.

Short-lived Solutions For Horse Traffic

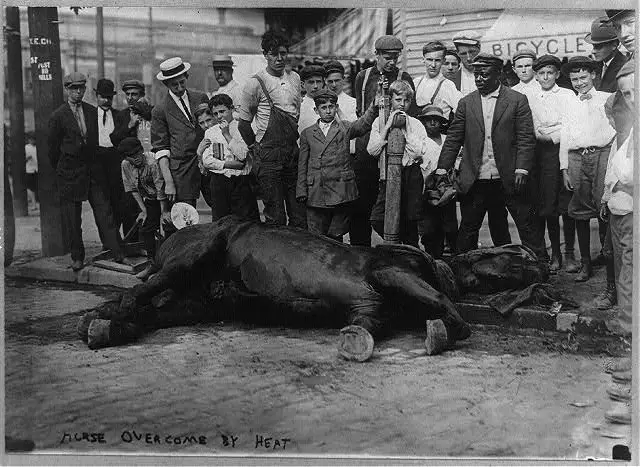

The rich paid to have their roads strewn with straw to reduce noise. The situation became so bad that the city paved some streets in wood, cut in wide blocks, and laid with the grain up, to cut down on the noise – but the timber absorbed horse urine and stunk even more, and it rotted away within five years while sett blocks would last virtually forever. However, set blocks were uneven, and people and horses would easily trip. A lame horse would be shot and left to rot for up to three months because there were no machines to haul away such heavy carcasses.

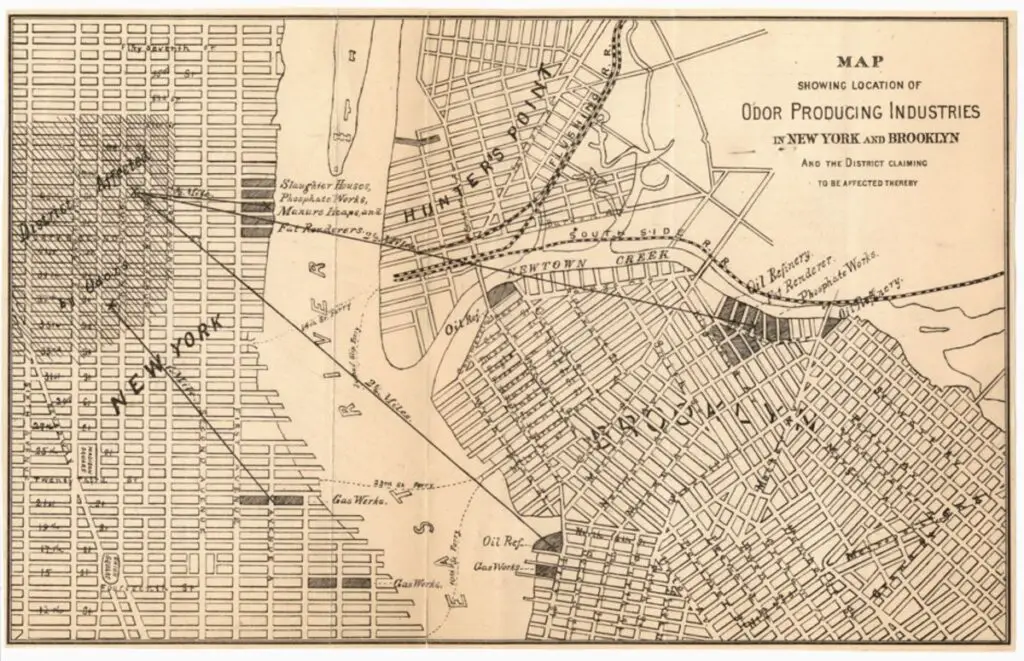

The situation was so bad that in conjunction with the gas plants, giant phosphate plants, oil refineries, slaughterhouses, and glue factories, NYC published a “Stench Map” showing where the prevailing winds would blow the stink. It was untenable.

Politicians Look To Clean Up the City

Teddy Roosevelt, before he became Commissioner of Police, was hired to clean up the corruption in the police department, which had even fought a deadly civil war between competing departments, was first offered the job of cleaning the streets. He turned it down. “No one can clean up that mess,” he declared.

Even though it was illegal, the city pushed the manure into the harbor or onto barges and had it dumped at sea, where it washed up on the beaches of Long Island, making the residents irate. The situation was so bad that bars of manure formed in the river that capsized ships and halted navigation requiring constant dredging. It was an absolute disaster.

How Detroit Handled Horses and Manure

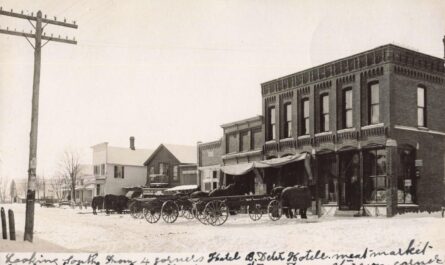

Prior to the automobile, Detroit, like many other cities, relied heavily on horses for transportation and other tasks. As a result, there was a significant issue with managing horse manure and urine.

In the city’s early days, horse manure was often collected and sold as fertilizer to local farmers. However, as the city grew and the number of horses increased, the volume of manure became too great to manage in this way.

By the late 1800s, the city of Detroit had established a department dedicated to the collection and removal of horse manure. The department employed men who would go around the city collecting manure from the streets and hauling it in carts. The manure was often taken to vacant lots on the city’s outskirts, where it was left to decompose.

However, this system could have been better. The collection and removal of manure were often slow, and piles of manure would often accumulate on the streets, causing health and sanitation issues. In addition, many residents complained about the smell and flies attracted to the piles of manure.

To address these issues, the city began to experiment with other solutions. One of these was to convert the manure into gas, which could then be used to power streetlights and other city infrastructure. However, this process was expensive and difficult to manage, and it has yet to become a widespread solution to the manure problem.

Ultimately, introducing the automobile in the early 1900s helped solve the manure problem in Detroit and other cities. As more and more people began to use cars for transportation, the number of horses on the streets declined, and with it, the volume of manure. The city no longer needed to rely on expensive and inefficient methods to manage the waste produced by horses.

Final Days of the Horse and Buggy Ends the Great Manure Crisis of 1894

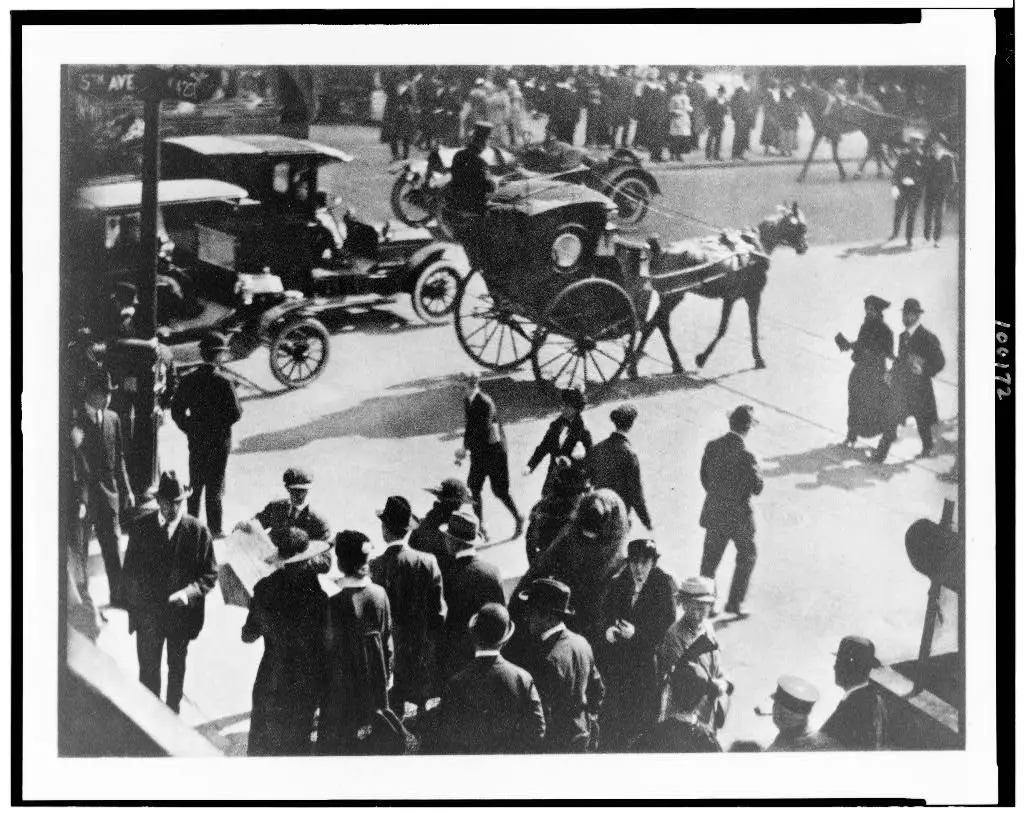

The problem was solved in stages, but the electric subway car and the invention of automobiles saved the city and cities worldwide. However, in Europe, earnest efforts at sanitation had gotten the problem in hand long before the US. The automobile was in its infancy in 1898 with only a handful of electric, steam, and gas cars, but by 1908, half of all the horses in NYC had been replaced by cars.

The impact on the horse market was so intense that people were frantically selling their horses for any price to the glue factories to get rid of them. The last horse-drawn fire engine was retired in NYC in 1922 in a lavish ceremony where the previous engine was called on a ceremonial fire call from a box. They raced from the station for the last time, chased by their Dalmations, to a non-existent fire where the horses were relieved of their jobs but preserved to live out their lives in a pasture as a reward for their service.

Final Thoughts On The Great Manure Crisis of 1894

The automobile and a man named Colonel Waring saved NYC. Waring was given absolute dictatorial control over the city’s clean-up, fired the Tammany no-shows, and had his men dress in white uniforms as they shoveled the manure away, day and night. He even made it a patriotic duty to clean the streets and put in wastebaskets, and organize trash removal. The city so hailed him for success that a ticker tape parade was held in his honor. But ultimately, it was the automobile that saved the city.