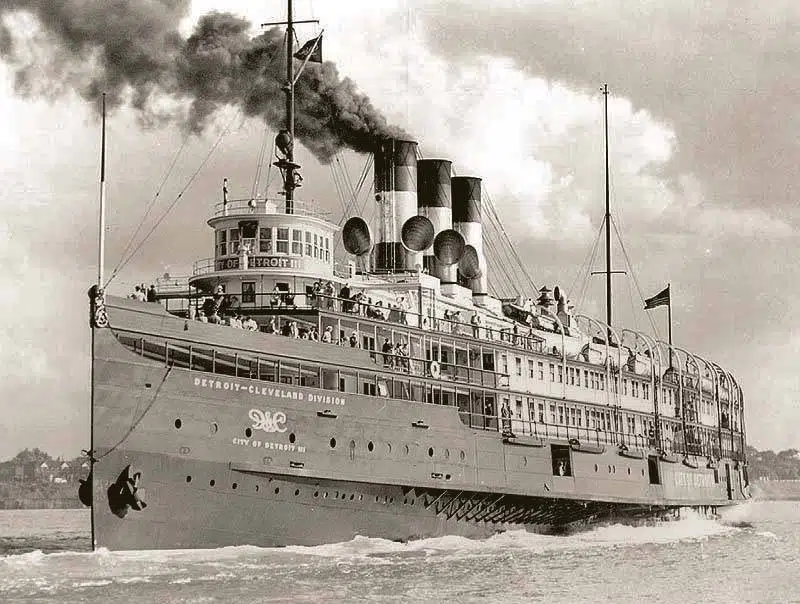

Beaver Island, Michigan is a remote emerald gem in northern Lake Michigan, known today for its quiet charm. But from 1840 to 1950, this island’s story was anything but quiet. Imagine a place that saw the rise and fall of a self-proclaimed king, the bustle of Great Lakes fishing fleets, the grind of logging trains through deep forests, and the steady beam of lighthouse lamps cutting through the fog. The history of Beaver Island Michigan is a tale of resilience and community on the frontier. In this blog post, we’ll journey through that history – from the Mormon monarchy of the 1850s to the hardworking island life of the mid-20th century – illustrated by remarkable historical photos from the island’s past.

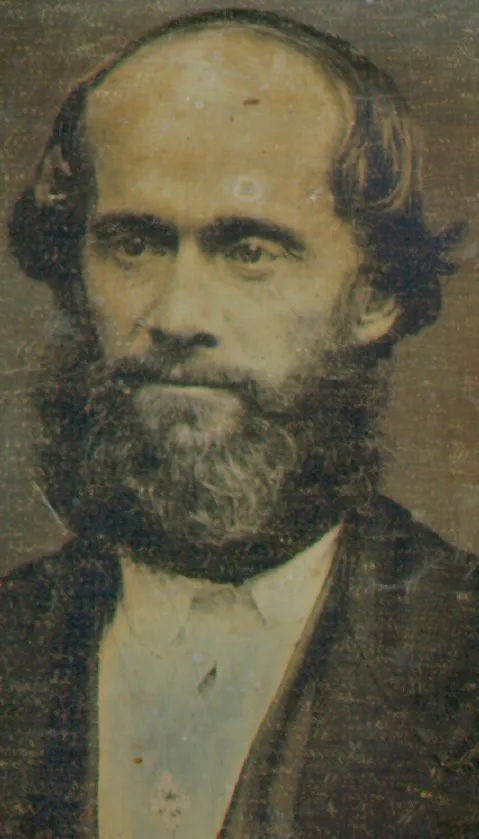

The Rise and Fall of King Strang’s Mormon Kingdom (1840s–1856)

The King Strang Hotel in St. James stands as a reminder of Beaver Island’s most unusual chapter – the brief era when the island was an American kingdom. In 1848, a charismatic Mormon leader named James Jesse Strang brought his followers to Beaver Island and declared himself their king. Strang’s breakaway sect built a settlement here, turning the wilderness into a fledgling colony. Under Strang’s rule, the community cleared land for farms, built houses and even started a local newspaper. Strang’s ambitions were grand: he had himself ceremonially crowned and even won a seat in the Michigan legislature while reigning from his island domain.

For several years the Mormon “Kingdom of St. James” thrived. However, Strang’s authoritarian ways – including strict codes of conduct and the practice of polygamy – bred resentment. Tensions mounted between Strang’s followers and the few remaining non-Mormon residents. In June 1856, matters reached a violent end. Strang was assassinated on the St. James dock by two disgruntled followers. Shortly after, an angry mob from Mackinac Island arrived by ship and forcibly evicted the entire Mormon colony. Thus ended America’s only self-proclaimed island kingdom. During their 8-year tenure, Strang’s people had built roads and tamed the land, but they left in haste, unable to reap the benefits of their work. Beaver Island’s brief royal saga was over, and a new chapter was about to begin.

America’s Emerald Isle: Irish Fishermen and a Thriving Harbor (1856–1890s)

With the Mormons gone, Irish American fishermen reclaimed Beaver Island. Many of the Irish families had lived in the area before and saw the island as a new opportunity. They arrived in force after 1856, coming from places like Mackinac Island and even directly from Donegal, Ireland. Before long, Beaver Island earned the nickname “America’s Emerald Isle” – a reflection of its primarily Irish population and culture. Gaelic (Irish language) could be heard in island homes and even in church services. By 1880, the island’s population swelled to 881 residents, with common surnames like Boyle, Gallagher, and O’Donnell appearing dozens of times in the census. Isolated by miles of water (especially when winter ice closed the lake), this community developed a distinct identity, rooted in Irish tradition and shaped by the challenges of island life.

Drying fishing nets on Beaver Island’s docks, circa early 1900s.

The Irish Beaver Islanders turned to the rich surrounding waters for their livelihood. In the late 19th century, commercial fishing became the island’s economic backbone. Beaver Island lay next to some of the finest fishing grounds in Lake Michigan, teeming with whitefish and trout. Thanks to that bounty, the islanders prospered. By the mid-1880s Beaver Island had become the largest supplier of fresh-water fish in the United States. Fishing boats crowded St. James Harbor, and the shoreline was lined with fish processing shanties, smokehouses, and stacks of wooden fish boxes. Each day, crews rowed out or sailed in small schooners, set miles of gill nets, and hauled in abundant catches.

This golden age did not last forever. In 1872, the advent of steam-powered tugs gave mainland fishermen the ability to make quick trips to the same fishing grounds. Beaver Island’s fleet suddenly faced stiff competition. The local fishermen’s near-monopoly was broken, and their catches began to fall. Worse, by 1886 the fish populations themselves were in decline due to overfishing. Nets that once came up bursting with fish began to come up disappointingly light. Between 1886 and 1893, the island’s annual fish harvest plummeted to roughly half its former level.

In an effort to save the fishery, the State of Michigan imposed new regulations, including a closed season during the fall spawning period. The independent-minded Beaver Islanders initially ignored the rules, insisting state laws did not apply to them. This led to a dramatic showdown in 1898 known as “the Battle of the Beavers.” That year, a state fish warden sneaked onto the island during the no-fishing week – only to end up in a moonlit boat chase with an islander who refused to pull his nets. Warning shots were fired from the warden’s boat (reportedly using a small cannon) before the fisherman was caught and arrested. The confrontation ended the islanders’ open defiance, but it became local legend, symbolizing their tenacity. By the end of the 19th century, Beaver Island’s fishing heyday was fading. The waters would continue to provide (and a fishing industry persisted into the mid-20th century), but the era of huge catches and packed harbors was over.

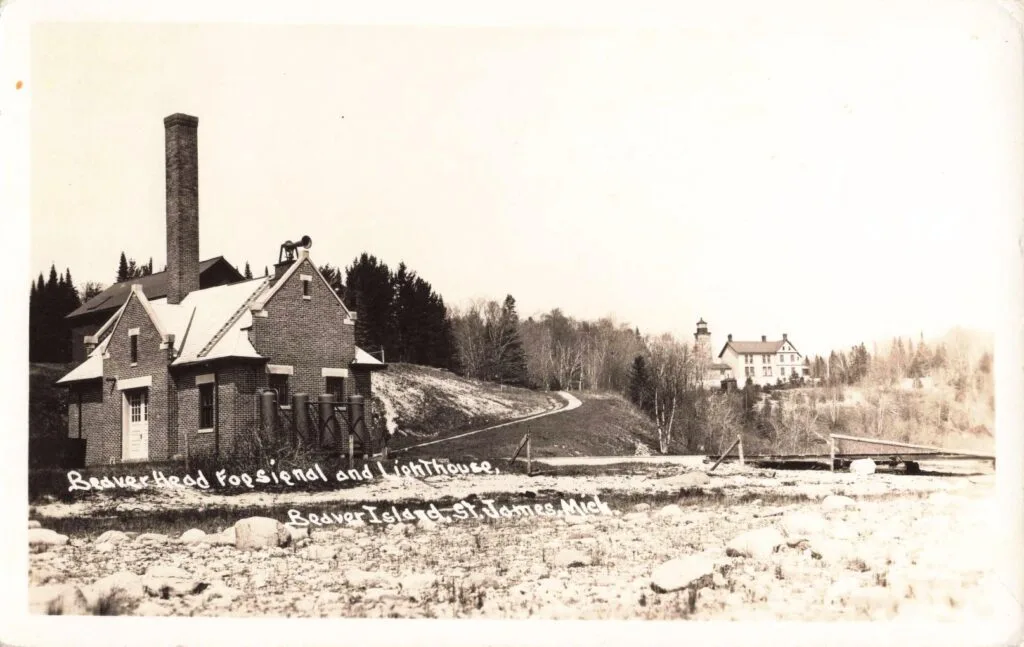

Guiding Lights and Lifesavers: Lighthouses and the U.S. Coast Guard

The U.S. Coast Guard Station at St. James (early 1900s) with rescue boats ready. As Beaver Island’s population grew in the 19th century, so did the number of ships passing through the surrounding waters – and with them, the dangers of shipwrecks. The U.S. government responded by establishing crucial maritime infrastructure on the island. In 1856, a lighthouse was erected at Whiskey Point, the sandy tip of St. James Harbor, to mark the entrance of the safe port. This St. James Harbor Light (also called Whiskey Point Light) helped guide vessels into Paradise Bay, which was known as the best natural harbor in northwestern Lake Michigan. To protect ships navigating past Beaver Island’s southern end, the taller Beaver Head Lighthouse had been built a few years earlier, in 1851. Its brick tower, 46 feet tall, stood on a lonely bluff amid dense woods, casting a fixed white beam for 16 miles across the water. A fog signal was added in 1890 – a loud steam siren that bellowed across the lake whenever thick fog rolled in.

Lighthouse keepers led solitary, diligent lives at these stations. For example, at Beaver Head Light, keepers and their families lived in an attached cottage at the base of the tower. They hauled oil up the winding stairs to fuel the lamp each night, polished the beacon’s lens, and fired up the coal-powered foghorn on soupy days. These lights were literal lifesavers for mariners and also symbols of safety for islanders. Many a Beaver Island resident, lying in bed on a stormy night, took comfort in seeing the distant flash of the lighthouse or hearing the foghorn’s low moan, knowing those signals kept passing ships off the rocks.

In 1875, Beaver Island’s role in maritime safety expanded further with the establishment of a U.S. Life-Saving Service station at St. James. (The Life-Saving Service was the precursor to the modern Coast Guard.) The station was situated near the harbor light and was staffed by a crew of surfmen trained to rescue shipwreck victims. These men were often local fishermen familiar with the lake’s fury. Whenever a distress signal – a flare or a shout – came from a vessel in trouble, the life-saving crew would scramble. They launched a sturdy rowboat or sailboat, called a surfboat, into the gale, risking their lives to reach stranded sailors. Remarkably, in the late 1800s the Beaver Island station gained a reputation for never losing a life during a rescue – no victim and no rescuer drowned on their watch. This was an extraordinary record, given the many wrecks and storms of the era.

In 1915, the Life-Saving Service merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the U.S. Coast Guard. The station at Beaver Island became a Coast Guard station, and its mission continued seamlessly. The crew, typically 10–12 men, operated motorized lifeboats that could plow through heavy surf. Many of these Coast Guardsmen were island natives (or stayed on the island long enough to marry into local families). They performed rescues, maintained aids to navigation, and even helped fight fires in the community when needed. One unique aspect of Beaver Island was that for years the only telephone on the island was located at the Coast Guard station. In emergencies, islanders ran to the station to send telegrams or make calls for help. The Coast Guard station truly became a community hub.

The presence of the Coast Guard also meant regular visits by larger vessels. Coast Guard cutters and buoy tenders would stop by to deliver supplies, mail, or to service the light stations and offshore buoys. In the winter months, when commercial ferries could not run, a Coast Guard icebreaker might be the island’s only lifeline. One historic photo from the 1940s shows a Coast Guard cutter breaking through lake ice to reach Beaver Island’s dock, where islanders awaited essential goods. Such scenes underscore how isolated Beaver Island could be – and how vital the Coast Guard was in keeping it connected to the outside world.

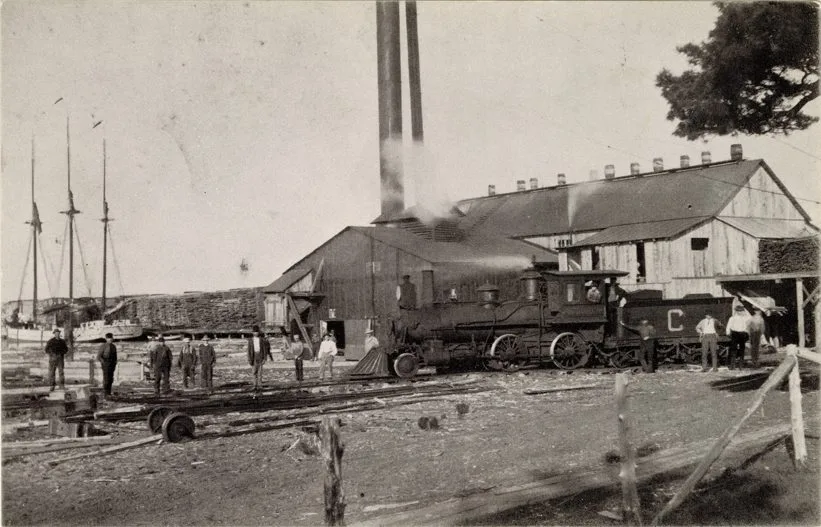

Timber! The Logging Boom and Railroads (1900–1915)

Beaver Island logging crew and locomotive, early 1900s. Around the turn of the 20th century, Beaver Island experienced an economic boom of a different sort. Logging had been practiced on a small scale for decades (even King Strang himself cut wood on the island in 1847 to earn passage money), but in 1903 a major commercial operation arrived. The Beaver Island Lumber Company bought up thousands of acres of forest on the island and built a large sawmill on St. James Harbor. To transport logs from the interior forests to the mill, the company constructed a narrow-gauge logging railroad. Steel rails stretched over ten miles southward from the harbor, looping around inland lakes and reaching deep into the hardwood groves. Small steam locomotives – likely wood-fired “dinky” engines – pulled long trains of flatcars loaded with enormous logs.

At the logging camps in the island’s dense woods, over one hundred lumberjacks labored with saws and axes. They felled towering maple, beech, and birch trees, then hauled the logs by horse or winch to the nearest rail spur. The trains would then pick up the timber and chug back to the mill in St. James. Islanders still tell tales of these trains: how the locomotives sometimes struggled on the tight curves and hills, occasionally tipping over or derailing from the heavy load. (One accident even killed an engineer, highlighting the danger of the work.) The sawmill by the harbor turned out shingles, lumber, and cordwood at a prodigious rate. Ships arrived regularly to carry off the finished wood products to markets on the mainland. For Beaver Island, which had been economically stagnant for a while, the logging operation brought a burst of activity and jobs. The lumber company built housing for workers, and a new neighborhood known as “Freesoil Avenue” sprang up in St. James to accommodate the influx of lumbermen and their families. These newcomers added some diversity to the island’s predominantly Irish population.

The logging boom was intense but short-lived. By 1915, the Beaver Island Lumber Company had depleted the easily accessible timber. The great forest that once blanketed much of the island’s west side was considerably thinned out. The company decided to close down. They removed the rails (most were pulled up and shipped elsewhere), dismantled the big mill, and left Beaver Island in 1915–1916. Many islanders might have expected Beaver Island to revert to its quiet fishing-dependent ways after the lumbermen left. Interestingly, quite a few of the loggers decided to stay on the island permanently. They married local girls or brought their families, integrating into the community. In that way, the legacy of the logging era lived on in the island’s people and in the opened-up land (some former logging tracts became new farms or orchards). The logging railroad itself was gone, but locals repurposed some of its grade as rough wagon trails, and every so often someone would stumble on an old railroad spike in the woods – a rusted reminder of the time Beaver Island roared with the sound of the lumber trade.

A Beloved “Doctor” and Island Community Life (1890–1920s)

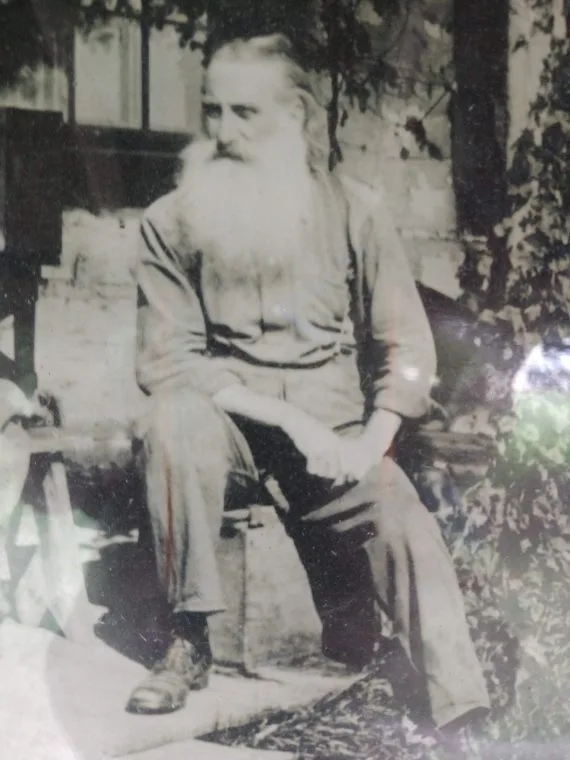

While industries rose and fell, the fabric of day-to-day life on Beaver Island was woven by ordinary people and local heroes. One such figure was Feodor Protar, fondly remembered as “Dr. Protar” – though he wasn’t a doctor at all. Protar was born in Estonia (some sources say he was a distinguished actor in Europe) and emigrated to America in the late 19th century. In 1893, seeking peace and purpose, he came to live on Beaver Island in a one-room log cabin. Embracing a simple, rustic lifestyle, Protar grew his own food and followed the philosophical teachings of Leo Tolstoy. But it was his compassion that made him a legend. Seeing that the island had no year-round physician – and that mainland doctors were often unreachable in winter – Protar stepped into the role.

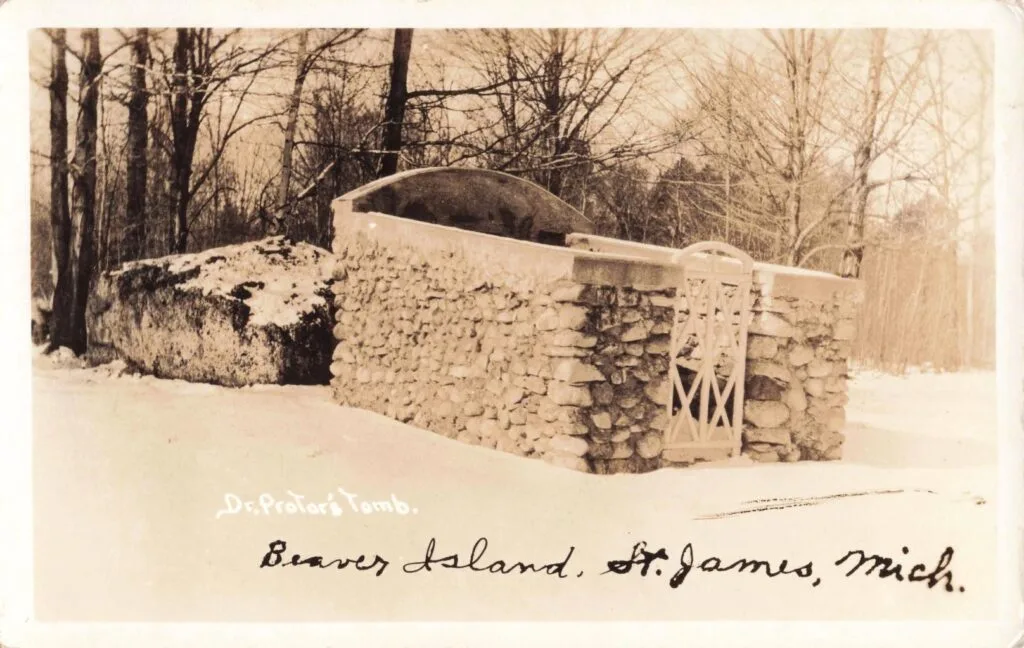

Dr. Protar’s Tomb, built by islanders in 1925, on Beaver Island. Photo circa 1930. For over thirty years, Feodor Protar ministered to his neighbors’ health needs without a medical license and without asking for payment. He had a basic knowledge of medicine and pharmacy, and he kept a stock of remedies. When someone fell ill or got injured, Protar would show up at their door, sometimes after trekking miles through snow. He treated ailments with poultices, herbal tinctures, common-sense nursing, and an abundance of kindness. In the small Beaver Island community, Protar became cherished for his selflessness. The Michigan authorities were aware that an “unlicensed” doctor was practicing on Beaver Island, but they wisely looked the other way – Protar was the only help available, and he clearly was saving lives and improving health. Islanders came to regard him as a humble saint.

When Feodor Protar died in March 1925, the community mourned deeply. In an extraordinary tribute, island residents decided to create a permanent monument at his burial site. They constructed a stone tomb on a bluff overlooking Protar’s favorite patch of woods. Using beach stones and concrete, they built thick walls around his grave and installed an iron gate. A bronze plaque was added, inscribed with words of gratitude for “his many years of faithful service” to the people of Beaver Island. To this day, “Dr. Protar’s Tomb” is a point of pride and pilgrimage on the island – a place where visitors learn about the kindly hermit-doctor who exemplified the island’s spirit of neighborly care.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, island life was rugged but tight-knit. Farming supplemented fishing for many families – potatoes, hay, and hardy vegetables were grown in the thin soil to help cut down on costly freight from the mainland. The Catholic parish, established in the 1860s, was the social and spiritual center; colorful priests like Father Peter Gallagher (known to have a fiery personality and even a talent for fistfights) became local legend. On Sunday afternoons or winter evenings, islanders gathered for dances, house parties with fiddles and accordions, or “bees” to help each other build barns and boats. The arrival of the mail boat was an event, bringing newspapers, letters and goods. News from the mainland traveled slowly; even into the 1920s, winter mail might come via a daring ice sled journey over the frozen lake before regular winter ferry service was established in 1926. In short, Beaver Islanders relied on one another and lived simply, creating a rich tapestry of memories to carry them through the harder times.

Mid-Century Challenges and Changes (1930–1950)

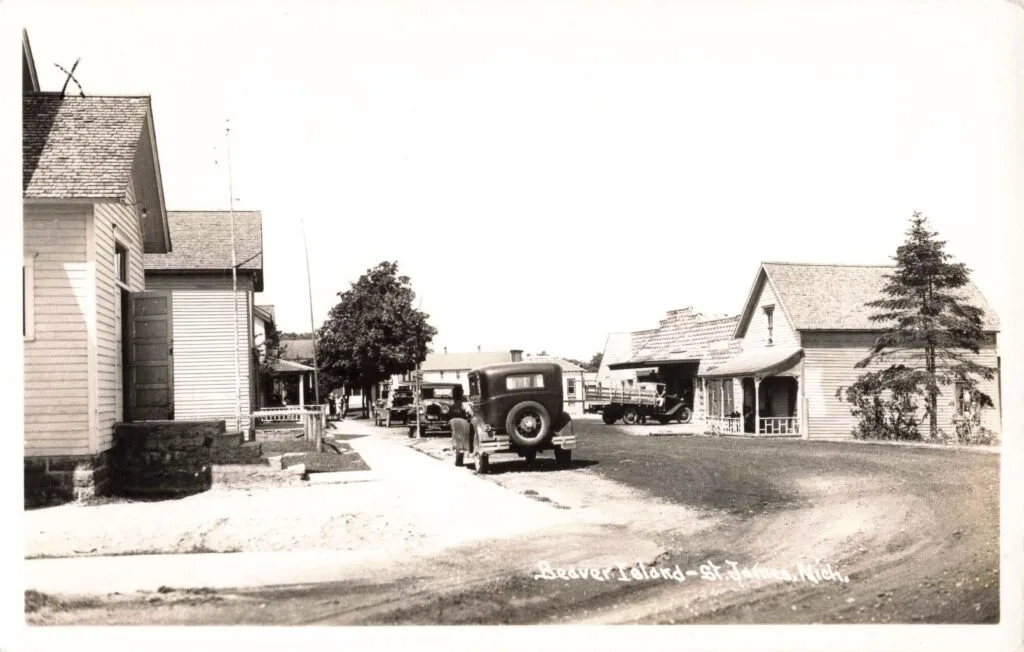

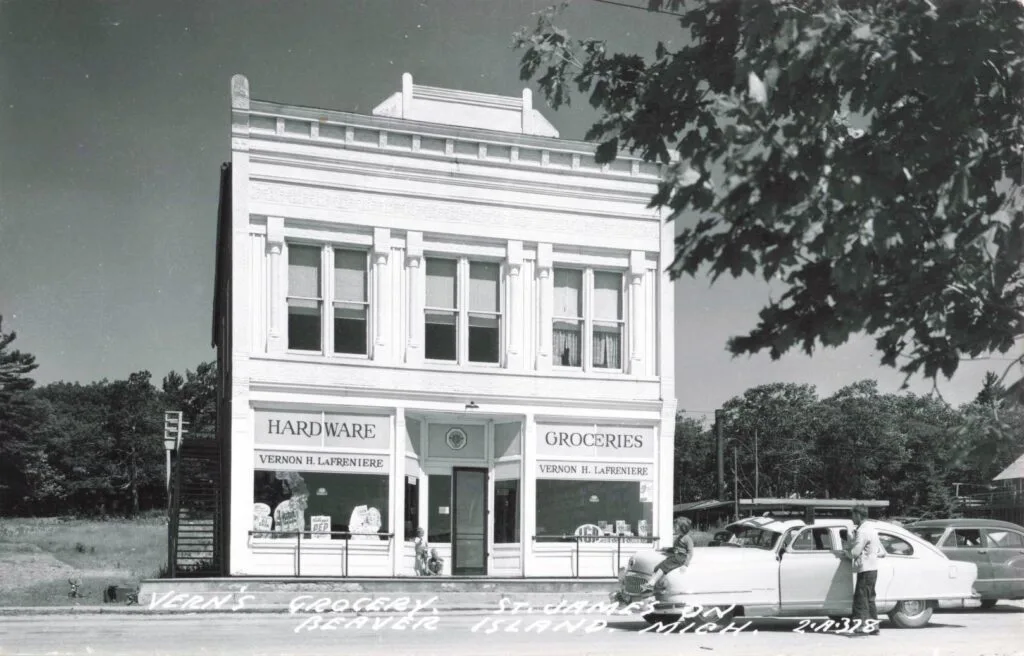

Main Street of St. James, Beaver Island, in the 1930s. By the 1930s, the modern era was cautiously making its way to Beaver Island. Photographs from that decade show a few 1930s-era cars parked on Main Street, and modest wood-frame storefronts in St. James. One of those shops, Vern’s Grocery and Hardware, became a local institution (its proprietor, Vernon LaFreniere, served islanders and visitors for many years). Such businesses catered to the everyday needs of island life – selling canned goods, kerosene, nails, boots, and everything in between. People still mainly got around by horse-drawn wagon or on foot, but the presence of automobiles signaled change. In 1939, a diesel generator power plant was built on the island, finally bringing electricity to homes and allowing radios, refrigerators, and electric lights to ease daily life. (Before that, only a few places like the Beaver Hotel – later renamed the King Strang Hotel – and the Coast Guard station had their own small generators for limited electric power.) The island’s first airplane service started in the 1940s as well, further shrinking the distance between Beaver Island and mainland Michigan.

Despite these improvements, the mid-20th century was a challenging time for Beaver Island. The population, which once exceeded 1,000 in the 1880s, was in steady decline. Many young people left after finishing school, seeking jobs in Chicago, Detroit, or joining the armed forces during WWII. Those who remained kept up traditions of fishing and small-scale farming, but the economic base was shrinking. The commercial fishing industry took a severe hit in the 1940s when the invasive sea lamprey entered Lake Michigan and decimated native fish stocks (especially lake trout and whitefish). As catches dwindled to almost nothing, families that had fished for generations faced tough decisions. By the early 1950s, some of the last professional fishermen pulled up their nets for good.

Meanwhile, large cargo ships were modernizing and changing routes, and Beaver Island was no longer a necessary stop for the lake freighters of the mid-1900s. Shipping traffic bypassed the island, and with it went some of the secondary jobs like loading freight or cutting wood for steamers. All these factors caused the community to shrink. In fact, by the late 1940s, the year-round population of Beaver Island had fallen below 200 residents. Many feared that the island was on the verge of becoming a ghost town – the school’s enrollment was tiny, and it was a struggle to keep a doctor or other essential services on the island.

A U.S. Coast Guard cutter unloading supplies at St. James, Beaver Island, circa 1940s. In these lean years, Beaver Island’s isolation was most keenly felt in winter. When thick ice closed the sea lanes, the island could go weeks or even months without a visit from the mainland. The photo above captures a dramatic moment: a Coast Guard cutter has cut through the ice to deliver vital supplies. On the snow-covered dock, islanders await crates of food, fuel barrels, and mail bags being hoisted ashore. Such relief trips were literal lifelines. They illustrate how dependent the island community was on outside support by mid-century. Yet they also show the determination of the people and their Coast Guard allies to keep Beaver Island inhabited against the odds.

By 1950, Beaver Island was at a crossroads. The old industries – the fishing, the large-scale logging, even the days of being a strategic harbor – had all faded. What remained was a peaceful, if economically fragile, community with extraordinary history in its rear-view mirror. Little did those remaining families know that a rebirth was on the horizon. In the coming decades (starting in the 1960s and especially late 1970s), tourism and recreation would breathe new life into Beaver Island, capitalizing on the very history and natural beauty that had so long been seen as obstacles to progress.

Legacy of a Storied Island

The history of Beaver Island Michigan is a rich saga of adaptability and tenacity. This small island witnessed a unique social experiment with a Mormon monarch, became a powerhouse in Great Lakes fishing, and saw its forests fall to feed America’s growth. It hosted heroes like the surfmen of the Life-Saving Service and the humble Dr. Protar who tended the sick. The legacy of those years from 1840 to 1950 lives on in the island’s landscape and in the stories passed down by descendants. Visitors today can stroll the quiet streets of St. James and see echoes of the past: the King Strang Hotel, once the only hotel on the island, still stands on Main Street as a private lodge (a literal monument to the Strang era). The stone ruins of fish processing sheds and the frames for drying fishing nets can be found near old harbor docks. At Whiskey Point, the 1856 lighthouse still shines each night, maintained as a symbol of safety and heritage. Down a wooded path, the iron-fenced Protar’s Tomb stands silently among rustling trees, speaking to the gratitude of a bygone generation.

Beaver Island’s population did rebound later in the 20th century, thanks to tourism and improved transportation. But the period from 1840 to 1950 remains the heart of its identity – a time when the island was isolated yet bustling in its own way, forging a distinctive culture. Understanding this history adds depth to every experience on Beaver Island. Whether you’re a history buff intrigued by America’s only kingdom, or an adventurer drawn to the Great Lakes, Beaver Island offers a fascinating glimpse into a resilient island community. The History of Beaver Island Michigan is more than dates and events; it’s the story of people making a home against the odds, anchored by faith, fellowship, and the enduring promise of the Great Lakes.

Sources

Historical information in this post was drawn from the Beaver Island Historical Society archives, contemporary newspaper accounts, and scholarly works. Key references include Beaver Island’s “A Rich History”, Clark Norton’s travel history article, and records from the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office. These sources document the unique events and people that shaped Beaver Island’s destiny.