The Detroit numbers racket history is central to understanding Michigan’s underground lottery culture. Also called the policy game, the numbers racket thrived from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century. By the 1920s, Detroit’s illegal lottery was the state’s most pervasive, shaping neighborhood economies, fueling organized crime, and leaving a mark that lasted long after the state lottery arrived.

Origins of the Numbers Game in Michigan

In Michigan’s largest cities the numbers game – an illegal daily lottery – took root in the late 19th century. By 1887 Detroit alone had on the order of 160 “policy” shops where players placed secret wagers . The city’s explosive growth (nearly 10× population rise from 1880–1920) and booming auto industry brought waves of working-class and African-American migrants, providing a fertile clientele.

As one historian notes, by the 1920s Detroit’s illegal numbers racket had become the state’s most pervasive lottery . (Nationwide, policy gambling was especially common in Black urban neighborhoods .) The game itself was simple – players bet on a three-digit number, often drawn from financial or racing figures – but it generated huge sums and many little “bankers.”

Detroit and the Numbers Racket

Detroit’s 1920s downtown reflected the boom that fueled underground lotteries. In this era ethnic and racial communities alike ran local games. Detroit’s old Jewish and Italian East Side housed Prohibition-era gangs, and by the 1920s one syndicate – the Jewish “Purple Gang” – took over bootlegging and then quickly seized control of the numbers racket . (The Purple Gang ran nightclubs and eateries where people could buy tickets and placed bets .) As their power grew, the Purples essentially dominated Detroit’s lottery until the early 1930s, when internal strife and police action broke up the gang.

Detroit’s Policy Kings: Roxborough and Watson

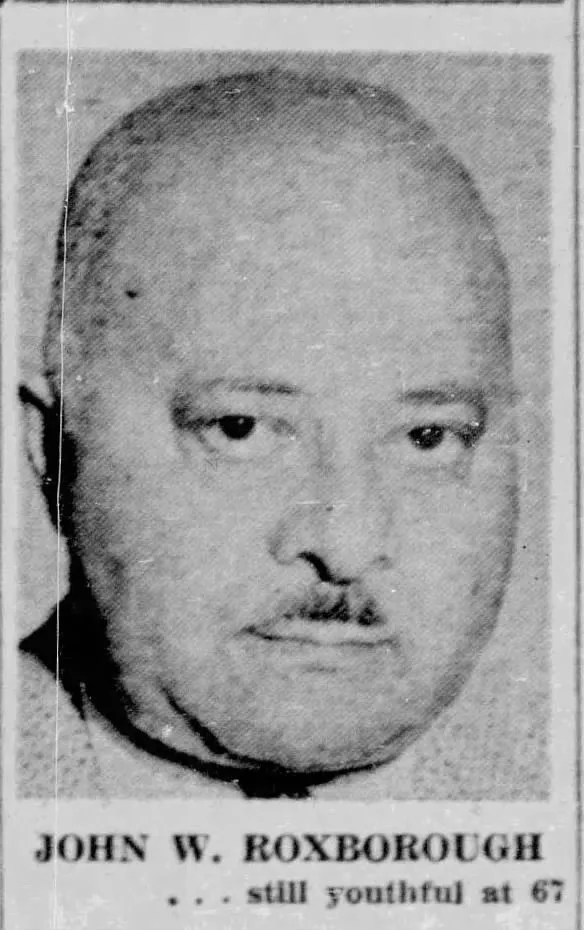

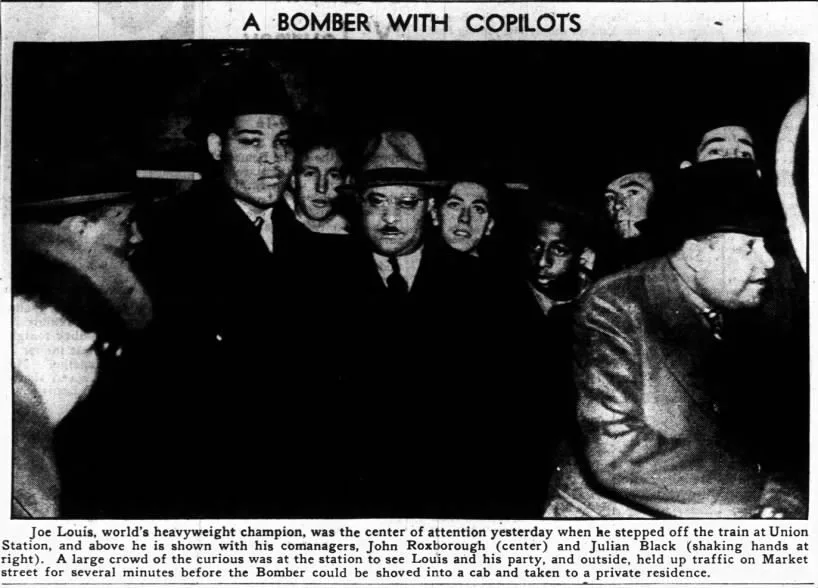

In the wake of Prohibition, Black Detroiters began to run the numbers business on their own. By the mid-1930s John W. “Roxie” Roxborough – famous as boxer Joe Louis’s manager – set up the leading operation. He fronted the game through an insurance company and employed thousands of “writers” and runners. Treasury agents later confirmed Roxborough’s outfit used ~6,000 people and grossed roughly $800,000 a year (about $6,000 weekly profit). Roxborough’s chief partner was Everett I. “Yellow Dog” Watson, who ran a rival policy house.

Together they built a combined lottery empire sometimes estimated at $10 million per year . In 1940 a grand jury probe (spurred by a 1939 suicide letter from a disaffected gambler) indicted 135 people – including Mayor Richard Reading, police officials, and Roxborough and Watson – for conspiracy to protect the lottery . In December 1941 a jury convicted Reading, Roxborough, Watson and others of running a $10 million/year policy racket in 1938–39 . (Roxborough ultimately served about 21½ months in prison .)

He and Everett Watson split the Detroit numbers racket profits and even donated some of their wealth to Black institutions . After their conviction, Roxborough largely withdrew. In the 1950s another Black entrepreneur, Eddie Wingate (1917–1990), came to dominate Detroit’s lottery. Wingate, a former Ford plant worker, ran policy out of Paradise Valley, invested heavily in local nightclubs, hotels and a record label, and was known as a tough boss who even intimidated Detroit’s Italian Mafia figures out of the numbers trade . Wingate legally avoided prison for racketeering; he finally fell to a tax-evasion case in 1977 and later declared that the city’s crackdown had been unfair to the Black community .

Beyond Detroit: Numbers Rackets Across Michigan

After Detroit, other Michigan cities also had similar underground lotteries. Flint and Saginaw, for example, saw growing African-American populations in the 1940s–60s and presumably had their own “policy banks,” though detailed documentation is scarce.

A 1970s FBI bulletin (cited in press) reported that illegal numbers operations were active across multiple counties (Wayne/Detroit, Oakland, Genesee/Flint) . Mid-century newspaper archives do record occasional raids and prosecutions of “policy” gamblers in places like Flint and Grand Rapids, but no comprehensive histories of those cities’ rackets have been published. In general, wherever working-class or immigrant enclaves existed in Michigan’s industrial towns, small-time lottery games flourished much as they did elsewhere in the U.S.

Political Scandals and Law Enforcement Raids

St. Louis, Missouri • Sat, Mar 29, 1941

Page 11

Michigan authorities launched several high-profile crackdowns. The 1939 suicide of Janet MacDonald (a gambler’s partner) exposed widespread corruption: her letters named police who took bribes to protect the racket and “triggered one of the most explosive investigations” in Detroit history . In April 1940 a one-man grand jury opened the probe that led to indictments against Mayor Reading, Roxborough, Watson, and dozens of officers . The December 1941 conspiracy trial ensnared the mayor and major operators .

These prosecutions briefly disrupted Detroit’s policy banks and embarrassed city hall. However, numbers gambling merely relocated rather than vanished. Through the 1950s and 1960s police continued to chase street casinos and small-time lottery rings citywide. Ultimately, the decisive blow came in 1972 when Michigan launched a legal state lottery. With a state-sponsored draw offering big prizes for a nickel, the old three-digit game “died of gradual evanescence,” as one study puts it . By then the Detroit numbers game had endured roughly seven decades, and legalization along with continued policing finally drove what remained of the underground business out of most neighborhoods .

Community Impact of the Numbers Racket

Despite its illegality, the Detroit numbers racket had deep social roots. In Detroit’s segregated economy, the lottery often acted like a community bank. Researchers emphasize that policy bankers provided jobs and credit when white institutions would not. As one Detroit historian notes, “Numbers gambling offered professional employment opportunities for blacks when other avenues were denied… [and] served as a financial institution for those who lacked access to mainstream financial institutions” .

Indeed, many Black Detroiters credit the game’s profits with seeding local businesses – hotels, barbershops, insurance offices and more – that mainstream banks would not fund . Numbers-runner Sunnie Wilson later argued that disrupting the policy game in 1940 “hurt the economic condition of the Black community” because it took away a key source of capital . In Felicia George’s words, Detroit’s illegal lottery ultimately became “a community resource and institution of solidarity for Black communities” during eras of racial segregation .

At the same time, most mainstream sources demonized the numbers game. Newspapers labeled it “the poor man’s game” or a destructive “policy racket” that preyed on the disadvantaged. In Detroit’s press around 1900–1915, policy was condemned as public menace and linked with poverty or crime . This social ambivalence – numbers as both community lifeline and illicit vice – was typical of African-American urban life nationwide.

After 1972, when state lotteries made gambling legal, many Black residents nostalgically compared the old numbers to a now-outlawed tradition. In short, Michigan’s street lottery scene played a significant cultural role in Black and immigrant neighborhoods: it was a risky business that nonetheless provided hope and support to populations shut out of the mainstream economy .

Sources For Detroit Numbers Racket History

- Davis, Bridgett M. The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers. Little, Brown and Company, 2019.

- George, Felicia B. When Detroit Played the Numbers: Gambling, Race, and Power in the Motor City. University of Illinois Press, 2023.

- “John W. Roxborough.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_W._Roxborough.

- “Purple Gang.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purple_Gang.

- “Stephanie St. Clair.” The Mob Museum, https://themobmuseum.org/notable_names/stephanie-st-clair/.

- “The Engines and Empires of New York City Gambling.” The New Yorker, 11 Aug. 2025, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/08/11/the-engines-and-empires-of-new-york-city-gambling.

- “When Detroit Played the Numbers.” HistoryHit, https://www.historyhit.com/queen-of-numbers-who-was-stephanie-st-clair/.