The summer of 1812 marked the first American offensive of the War of 1812, directed from the Michigan Territory, as part of the American invasion of Canada. General William Hull, the Governor of Michigan Territory, led U.S. forces across the Detroit River with high hopes of a quick victory. Instead, a series of setbacks unfolded: small but pivotal skirmishes, the surprise loss of distant outposts, and a climactic surrender that handed the British a stunning early triumph. We outline the key events of the Michigan campaign in 1812 – from Hull’s initial invasion in July to the disastrous surrender of Detroit in August – and examine the tactics, leadership decisions, and outcomes that shaped this dramatic chapter of the war.

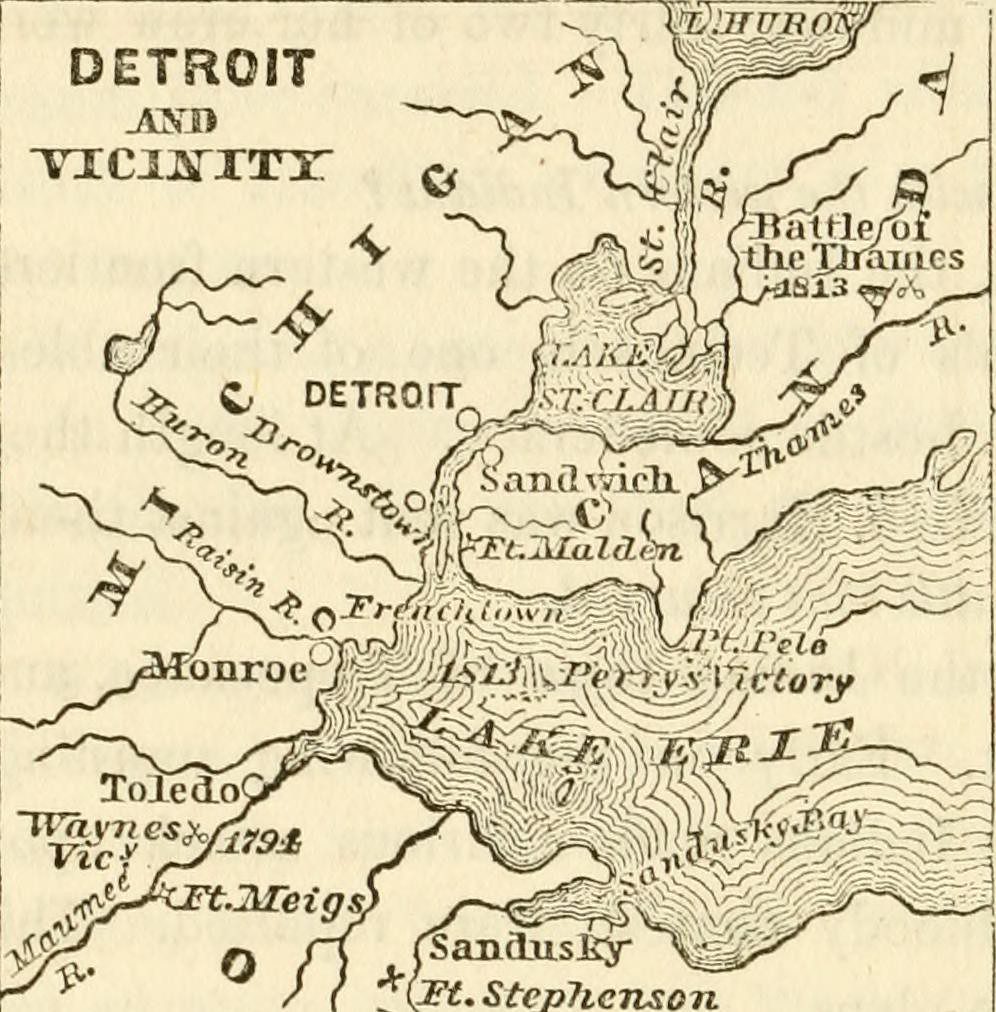

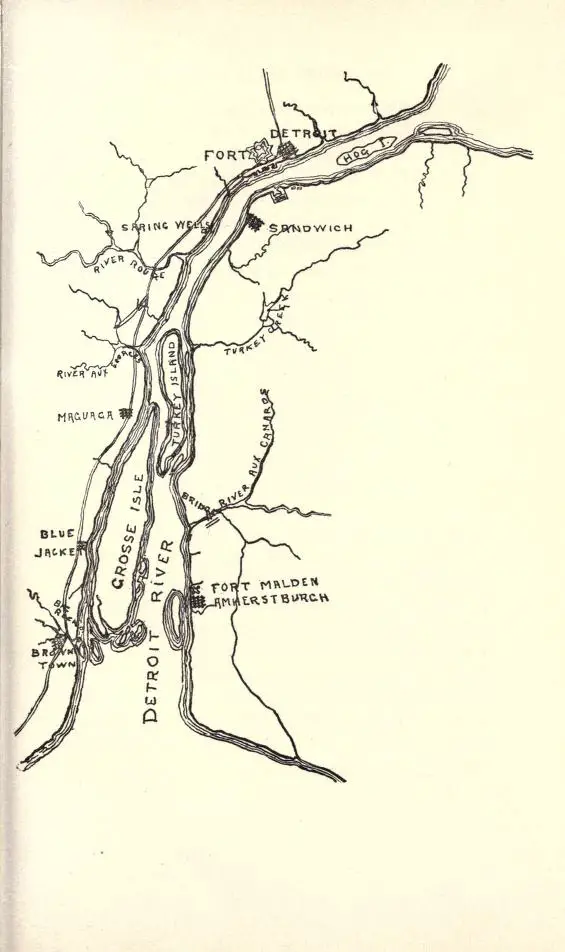

Map of the Detroit frontier in 1812, highlighting key locations such as Detroit, Sandwich (Windsor), Fort Amherstburg (Malden), and Brownstown.

Table of Contents

July 12, 1812 – General Hull’s Invasion of Canada from Detroit – Video

On July 12, 1812, Brigadier General William Hull launched the United States’ first invasion of Upper Canada. Hull’s army of roughly 2,000 militia and regulars crossed the Detroit River unopposed and occupied the Canadian village of Sandwich (present-day Windsor, Ontario). His initial objective was Fort Amherstburg (also known as Fort Malden) located about 16 miles south, which housed a small British garrison. Hull hoped a bold strike would secure the fort and rally local Canadians to the American cause. Once across the river, he even issued a grandiose proclamation warning Canadians against supporting the British. However, despite the confident start, Hull’s advance stalled soon after crossing.

Supply Line Concerns From The Start

Hull hesitated to assault Fort Amherstburg due to logistical and tactical concerns. He lacked heavy artillery to reduce the fort’s defenses and grew fearful that his long supply line back to Ohio could be cut by British patrols or their Indigenous allies. In the ensuing days, his troops engaged in minor skirmishes that revealed the risks ahead.

For example, on July 16 a detachment of U.S. troops under Col. Lewis Cass skirmished with a British outpost at the River Canard near Amherstburg. Although the Americans briefly seized a bridge, they encountered stiff resistance from a few British regulars and Menominee warriors guarding the approach. The British defenders, though outnumbered, managed a fighting withdrawal, even inflicting casualties and stalling the American reconnoitering force.

Hull, seeing these signs of organized resistance, became increasingly cautious. He recalled his advance parties and dug in at Sandwich rather than pressing the attack.

The British And Tecumseh Respond

Meanwhile, British Commander Isaac Brock and the Shawnee leader Tecumseh began coordinating a defense. British troops and Native American warriors harassed Hull’s outposts, keeping the Americans off-balance. Sniper fire and raids from Indigenous fighters (many of them Tecumseh’s Shawnee and other Great Lakes warriors) created a sense of vulnerability among Hull’s men.

Hull’s aggressive momentum faded, replaced by a defensive posture as he awaited reinforcements and supplies. What started as a bold invasion was now a tense stalemate on the Canadian side of the Detroit River. Hull’s overcaution and the effective skirmishing tactics of the British and their allies foreshadowed further trouble for the American campaign.

Tactical Analysis

The Michigan campaign in 1812, from General Hull’s initial plan, was sound in theory – strike a weak British position quickly. However, his indecision and fear of isolation undermined the invasion. Without adequate artillery, he doubted he could take Fort Amherstburg’s fortifications. His worries were amplified by British-allied Native forces threatening his communications. By pausing his advance, Hull surrendered the initiative. This gave the British precious time to reinforce and coordinate with Tecumseh’s warriors. In warfare, momentum is critical; Hull’s loss of momentum would prove costly when the British countered.

July 17, 1812 – British Capture of Fort Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island)

Even as Hull camped nervously at Sandwich, news arrived of a disaster from the far north. On July 17, 1812, British forces surprised and captured Fort Michilimackinac (often simply called Fort Mackinac) on Mackinac Island, at the straits between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. This remote U.S. outpost had not even learned that war had been declared when a joint force of British regulars, Canadian fur traders, and hundreds of Native American allies descended upon it. Captain Charles Roberts led about 600 men (including Ojibwa, Ottawa, Sioux, Menominee, and Winnebago warriors mobilized by the fur trading companies) from nearby St. Joseph Island in a swift canoe-borne expedition.

Out Flanked and Out Numbered

Fort Mackinac’s American commander, Lieutenant Porter Hanks, was caught completely off guard. At dawn on July 17, the British landed on Mackinac Island and quietly positioned a cannon on high ground overlooking the fort. They fired a single warning shot and sent a demand for surrender. The Americans, only 61 soldiers strong, were utterly surrounded and at a severe tactical disadvantage.

Lieutenant Hanks knew his men were outnumbered and feared that if he resisted, the large Native force would not be controllable once a battle began. Recalling the brutal frontier warfare of previous conflicts, Hanks chose to capitulate without a fight to avoid a potential massacre. In a bloodless victory, the British took Fort Mackinac and paroled the American garrison (the U.S. soldiers were released after swearing not to fight for the remainder of the war).

The Fall Of Mackinac Was A Strategic Blow For the Americans

The fall of Fort Mackinac had far-reaching consequences. Strategically, it gave Britain control of the upper Great Lakes and the vital fur trade routes. By seizing this fortress, the British also severed American lines of communication and supply in the Northwest. Equally important, the ease of this victory impressed many Native American tribes, convincing them to join or redouble their support for the British cause.

In fact, news of Mackinac’s capture directly undermined General Hull’s position. When Hull learned of the loss on July 29, he was stunned and immediately feared that hostile Native warriors from the north would swarm his exposed supply lines. The mere rumor of large bands of Ojibwa and other warriors coming south prompted Hull to rethink his entire campaign. His already shaky offense now seemed untenable.

Outcome & Tactics:

The British used surprise and psychological warfare to great effect at Mackinac. By arriving undetected and exploiting the Americans’ ignorance of war, they forced a surrender without firing a shot. This bloodless victory was a massive boost to British morale. It also served as a force multiplier – dozens of tribes, seeing British strength, rallied to Tecumseh’s confederacy in the following weeks.

For Hull, the loss of Mackinac was a grave blow. It meant his left flank (and the entire northwest frontier) was exposed. Cut off from reinforcements and seeing Native allies flock to the British, Hull grew even more cautious. Indeed, within days, he began considering withdrawal back to Detroit, a retreat that events would soon force him to make.

August 5, 1812 – Ambush at Brownstown (Near Flat Rock, Michigan)

By early August, General Hull’s supply situation was critical. American forces in Detroit depended on supplies and communications coming north from Ohio. To address this, Hull dispatched a column of 200 Michigan and Ohio militia under Major Thomas Van Horne to escort a vital supply convoy led by Captain Henry Brush, who was attempting to reach Detroit with cattle and provisions. On August 5, 1812, as Van Horne’s detachment marched south of Detroit near the Wyandot village of Brownstown, they walked into a carefully laid ambush.

Tecumseh Leads the Ambush at Brownstown

Shawnee war chief Tecumseh personally led a group of about 25 Native warriors (primarily Shawnee, with some Wyandot and others) to intercept the Americans. Although Tecumseh’s band was small, they knew the terrain and seized the element of surprise. In thick woods along Brownstown Creek, the Native warriors suddenly attacked Van Horne’s column from multiple sides.

The militia, caught off guard, panicked at the ferocity of the assault. Van Horne’s men returned fire but soon broke and scattered, leaving the supply mission in tatters. In the brief fight, the U.S. militia suffered around 18 killed and a dozen wounded, with others missing or captured, while Tecumseh’s force reportedly lost only one man. The engagement – often called the Battle of Brownstown – ended in a sharp defeat for the Americans, who retreated back toward Detroit without ever reaching Brush’s supply train.

Captured Letters Reveal A Weakness

Perhaps more damaging than the casualties was what the attackers found on the bodies of U.S. officers left on the field. Tecumseh’s warriors captured American mail and dispatches bound for General Hull. Among these papers were letters in which Hull candidly discussed his fears and the weakness of his position at Detroit. When British commanders gained this intelligence, it confirmed for them that Hull’s army was demoralized and short on provisions. General Hull, upon learning of Van Horne’s defeat, was shaken by the loss and the breach of his communications. This setback meant that no relief convoy was coming. Hull’s already low confidence plummeted further – Brownstown was a small skirmish, but it had strategic effects far beyond its size.

Analysis Of the Defeat at Brownstown

The tactics at Brownstown showcased the effectiveness of Native American irregular warfare on the Michigan frontier. Tecumseh’s ambush capitalized on stealth and surprise in wooded terrain, neutralizing the Americans’ numerical advantage. The psychological impact was significant: U.S. troops now felt vulnerable even on home soil, and Hull began to imagine hostile warriors behind every tree.

For Hull, the defeat confirmed his worst fears – that his supply lines were cut and that swarms of Indigenous fighters were closing in. It directly influenced his next move. With no supplies and facing attacks to his rear, Hull decided to pull back entirely from Canada. The failure at Brownstown effectively sealed the fate of Hull’s invasion, as it forced him into a defensive crouch at Detroit.

Early August 1812 – Hull’s Retreat Back to Detroit (By August 8, 1812)

Facing the twin blows of Fort Mackinac’s fall and the ambush at Brownstown, General Hull made a fateful decision: he abandoned his Canadian campaign. In the first days of August (by about August 3–8), Hull withdrew his army from Sandwich back across the Detroit River into Michigan Territory. The invasion of Canada, which had begun with such optimism on July 12, was over. Hull’s men dismantled their camps in Sandwich and hurried into the relative safety of Fort Detroit, a wooden stockade fort on the U.S. side. They left behind Canadian territory without firing a significant shot at Fort Amherstburg.

Hull’s retreat was a pivotal moment. It conceded the initiative entirely to the British. Major General Isaac Brock, the aggressive British commander of Upper Canada, had been anxiously watching Hull’s movements. Hull’s failure to press his advantage gave Brock the opening he needed. By withdrawing, Hull also sapped his troops’ morale – many of these citizen-soldiers felt demoralized, as their march into Canada had been for naught. The local Canadian populace, initially anxious under American occupation, now mostly remained loyal to Britain, having seen the invaders turn tail.

Inside Fort Detroit, Hull tried to bolster his defenses and confidence. He had roughly 2,000 men (including militia) and about 30 cannons. However, supplies were running low (the Brownstown ambush ensured that), and Native American warriors were now massing across the river in ever greater numbers. By early August, hundreds of Indigenous fighters from Tecumseh’s confederacy – Shawnee, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Wyandot, and others – had gathered to support the British at Fort Amherstburg. Hull could hear their war chants across the water and received reports of their movements in the Michigan woods. This fueled his anxiety. One U.S. officer noted that Hull was “trembling for the safety of Detroit and Michigan” in the face of such an alliance.

Commentary on Hull’s Tactics

In military terms, Hull’s pullback was strategically prudent but operationally disastrous. He was right that maintaining a foothold in Canada without supplies or artillery was untenable. However, the retreat meant surrendering any chance to take Fort Amherstburg, and it emboldened the enemy. Brock and Tecumseh were quick to seize the initiative Hull had relinquished.

Hull’s caution – some would say cowardice – gave the British the chance to go on the offensive. Indeed, as soon as Hull hunkered down in Detroit, Brock began planning an attack to capitalize on American demoralization. The stage was set for Detroit to become the next target. Hull, a Revolutionary War veteran in his late 50s, now faced a siege that would test his leadership to the breaking point.

August 15, 1812 – The Evacuation of Fort Dearborn and the Fort Dearborn Massacre

While Hull braced in Detroit, events far to the south added to the American woes. Fort Dearborn, a small U.S. fort on Lake Michigan (in today’s Chicago), had been ordered evacuated by General Hull in the wake of Fort Mackinac’s fall. Hull feared that Fort Dearborn’s tiny garrison could not be resupplied or reinforced, making it a ripe target for Britain’s Native allies. Captain Nathan Heald, commanding at Fort Dearborn, received Hull’s orders and prepared to abandon the post. On August 15, 1812, the fort’s garrison of about 66 soldiers, accompanied by 27 women and children (family members and civilian dependents), marched out intending to head for Fort Wayne in Indiana Territory.

An Ambush Awaits in the Dunes

They did not get far. Awaiting them just a mile and a half south of Fort Dearborn was a force of several hundred Potawatomi warriors, who were enraged by perceived American encroachment on their lands and emboldened by the spreading war. As the column of soldiers and civilians trudged along the lakeshore, the Potawatomi sprang their attack from behind dunes.

Captain Heald’s men fired a volley and briefly tried to charge the attackers, but they were quickly outflanked and overwhelmed. The confrontation turned into a bloody rout. Native warriors surged among the wagons; many of the American soldiers were killed outright, and the rest soon surrendered when further resistance was futile. In the melee, the Potawatomi killed not only combatants but also many of the civilians – women and children were not spared, which is why Americans later branded this event the “Fort Dearborn Massacre.”

Soldiers and Civilians Slain And Taken Prisoner

By the end of the 15-minute battle, approximately half of the evacuees lay dead. Captain William Wells (a noted Indian scout who was the uncle of Heald’s wife) was killed while heroically fighting to protect the women and children, and some Native accounts say his heart was cut out and eaten – a grim detail that became infamous in retellings.

Fort Dearborn Razed

In total, of the roughly 93 people who left Fort Dearborn, about 26 soldiers, all 12 militia, and at least 14 civilians were killed; the remainder were taken prisoner. The victorious Potawatomi burned Fort Dearborn to the ground that same day, erasing the American presence in the area. Prisoners were divided among the Native groups; some were ransomed months later, while others, tragically, did not survive captivity.

The Fort Dearborn attack, though geographically distant from Detroit, had a profound psychological impact on the Americans. It underscored how wide the Native alliance against the United States had grown. In Washington and across the frontier, the incident inflamed hatred and fear of Native Americans. The U.S. government became convinced that no Native tribe in the region could be trusted, and calls went out to retaliate.

Indeed, in later campaigns, General William Henry Harrison would cite Fort Dearborn while advocating for the forceful removal of Native peoples from the Northwest Territory. At the same time, the “massacre” served as a propaganda rallying point – newspapers painted vivid (if sometimes exaggerated) pictures of settlers butchered, fueling American resolve to avenge these frontier losses.

Tactical Note About the Massacre

The tragedy at Fort Dearborn underscores the risks associated with poorly executed evacuations in hostile territory. Captain Heald followed Hull’s order but arguably made critical mistakes, such as destroying surplus ammunition and liquor before the march (hoping to deny it to unfriendly Natives), but then losing the chance to negotiate effectively with the Potawatomi.

Some contemporaries argue that had Heald bargained more shrewdly or chosen a different route, the outcome might have been different. Regardless, the incident showed the ferocity of conflict on the frontier and the high stakes for Native nations as well. For the Potawatomi, who lost warriors too, this was part of an effort to push back American expansion. For the Americans, it was a stark lesson in the costs of war on the frontier – one that would not be forgotten when peace came.

August 16, 1812 – The Siege and Surrender of Detroit (Hull’s Surrender)

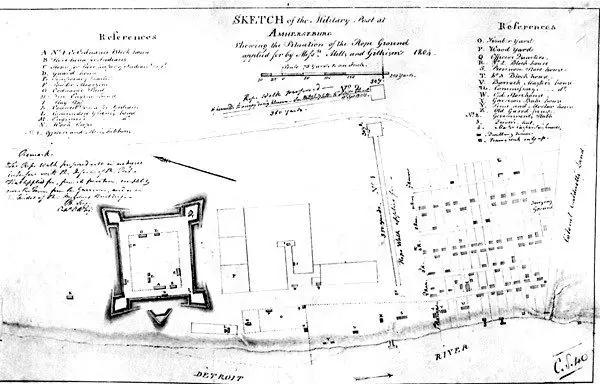

The culmination of the Michigan campaign took place in Detroit in mid-August. With Hull’s army confined to Fort Detroit and the town, British General Isaac Brock decided to strike quickly. Brock arrived at Fort Amherstburg on August 13 to take command. He met Tecumseh in person – beginning a legendary partnership – and the two agreed on a plan to force Hull’s surrender through intimidation and bold action.

Brock had only about 300 British regulars of the 41st Regiment, perhaps 400 Canadian militia, and a few light cannons at his disposal, but he was also supported by Tecumseh’s 600 or more Native warriors. Although Hull’s U.S. garrison was numerically larger (over 2,000 men), Brock rightly sensed that they were demoralized and that Hull feared a bloody battle with the Indians. The British plan was thus a combination of one part military assault and one part psychological bluff.

Hull’s Fears Are Used Against Him

On August 15, Brock sent a demand for surrender to General Hull under a flag of truce. In his letter, Brock pointedly warned Hull that if fighting began, Britain’s Native allies might be beyond his control, implying that a battle could lead to a massacre of Detroit’s defenders and even civilians. This was a deliberate attempt to prey on Hull’s fears (especially after news of Fort Dearborn). Hull refused to surrender immediately – replying, “I am prepared to meet any force at your disposal” – but inside the fort, his nerves were fraying.

Siege of Fort Detroit By Stelth

That night, Brock put his plan into motion. Under the cover of darkness, Tecumseh’s warriors stealthily crossed the Detroit River to the Michigan side. They moved through the forests north of Fort Detroit, their numbers obscured but their presence very much felt by the sentries. At first light on August 16, Brock led his regulars and militia across the river a few miles south of Detroit.

To add to the deception, Brock had outfitted Canadian militia in spare British redcoats, so that from a distance the American lookouts would think seasoned regulars were coming. As the British troops advanced toward the fort from the south, Tecumseh’s warriors staged demonstrations to the north, appearing and disappearing from the woods in a way that exaggerated their numbers. From inside Detroit, it looked as if thousands of Indigenous fighters might be circling.

Painting of allied commanders observing Fort Detroit on August 16, 1812, prior to the American surrender (Tecumseh on horseback and Brock with spyglass). The bold strategy and psychological tactics of the British and Native alliance compelled General Hull to capitulate.

Cannon From Canada

Brock’s artillery, positioned across the river at Sandwich, also opened up that morning, bombarding Fort Detroit with shot and shell. Though the cannons did limited physical damage, the noise and chaos of bombardment added to the panic inside the fort. General Hull, already pessimistic, was now genuinely terrified that if he fought and lost, hundreds of civilians in Detroit could be massacred by uncontrollable warriors. (Hull’s own daughter and grandchildren were inside the fort with him, a personal consideration that weighed on his mind.)

As Brock’s forces closed in, Hull made the fateful call to raise the white flag. Around 10:00 a.m. on August 16, a bedsheet of truce was hoisted over the fort’s wall. American gunfire ceased. Astonished but elated, Brock halted his troops and sent officers to negotiate the terms of capitulation.

Surrender of Detroit

The surrender of Detroit was formalized within a couple of hours. General Hull agreed to surrender Fort Detroit and his entire army – not just the fort’s garrison, but all outlying detachments and military stores in Michigan Territory. In one stroke, about 2,500 American soldiers (regulars and militia) laid down their arms. This included frontier units that weren’t even at Detroit (like the detachments under Colonels Cass and McArthur, who were marching nearby).

All of Michigan Territory was effectively handed to the British. Brock’s men marched into the fort and town, taking control without further resistance. The Stars and Stripes was lowered and the Union Jack raised over Detroit. The victory had been achieved with minimal casualties – reportedly, only a handful of people had been killed during the brief artillery exchange.

General Hull’s surrender at Detroit was one of the most stunning U.S. defeats of the war. He had given up a fortified position and an army without a pitched battle. News of Detroit’s fall spread rapidly, causing outrage and dismay throughout the United States. Hull himself was later court-martialed for cowardice and neglect of duty; he was convicted and sentenced to death, though President Madison spared him due to his Revolutionary War service.

British Hold The Entire Northwest

The British, meanwhile, exulted. They captured huge stores of cannon, muskets, and supplies that the Americans surrendered – including over 30 cannons, 2,500 muskets, and the armed brig Adams, which they added to their Lake Erie fleet. For the inhabitants of Upper Canada, Brock had delivered deliverance; many had feared Hull’s invasion would succeed, but now the threat was quashed. Tecumseh and his Indigenous confederacy were equally jubilant. Brock’s bold gambit and Tecumseh’s cooperation had saved Canada’s western flank, at least for the time being.

Tactical View: Why did Hull surrender so quickly?

In hindsight, Hull still had numerical strength and might have withstood a siege. But the general later justified his actions by claiming he faced an impossible coalition of British regulars and “hordes” of Native warriors from all directions. Indeed, the psychological impact of the Native presence was perhaps the decisive factor – exactly as Brock and Tecumseh intended. Hull believed that if he fought and lost, no mercy would be shown (a fear Brock stoked in his surrender summons). Thus, he chose to surrender to “save Detroit from the horrors of an Indian massacre,” as he wrote afterwards. His decision remains controversial, but it underscored the effective use of intimidation tactics by the British-Native alliance.

Aftermath – September 1812 and the Changing of Command

The collapse of the American Michigan campaign in August 1812 had major repercussions. In the immediate aftermath, British forces held undisputed control of Michigan Territory, and the American frontier lay exposed. The morale in the United States plummeted – what started as an attempt to seize Canadian territory had resulted in the loss of American soil. President James Madison’s administration faced public outrage and embarrassment. Conversely, British and Canadian morale skyrocketed. The victory at Detroit, coming so early in the war, convinced many undecided or neutral inhabitants of Upper Canada to stand with the British. Celebrations erupted in Canada, and General Brock became a national hero, lauded as the “Savior of Upper Canada.” Tecumseh’s reputation among his people and allies also soared; Indigenous support for the British cause reached its peak, as many tribes interpreted Detroit’s fall as proof of British strength and reliability.

Americans Respond To This Strategic Disaster

With General Hull a prisoner of war, the United States moved fast to regroup. In September 1812, President Madison appointed Brigadier General William Henry Harrison to assume command of the newly reorganized Army of the Northwest. Harrison was a seasoned Indian fighter (famous for victory at Tippecanoe in 1811) and was seen as more aggressive and capable than the disgraced Hull. His mandate was clear: retake Detroit and go back on the offensive in the Old Northwest. Harrison spent the fall of 1812 gathering troops – militia from Kentucky, Ohio, and the Indiana Territory – and securing supply lines in Ohio. It would take time to amass a force strong enough to challenge the British and their allies, especially with winter approaching. Indeed, Harrison did not march north toward Detroit until early 1813, after new U.S. Navy successes on Lake Erie. But his appointment in September signaled a turning point. The US government was determined to redeem the disaster in Michigan.

Focus Turns From Land to the Control of the Lakes

Looking beyond 1812, the events of that summer set the stage for later campaigns. In 1813, under Harrison’s leadership and after Commodore Perry’s naval victory on Lake Erie, American forces would recapture Detroit and defeat the British-Shawnee alliance at the Battle of the Thames (where Tecumseh was killed). But those victories lay in the future. As of late 1812, the legacy of the Michigan campaign was one of humbling lessons for the United States. It highlighted the perils of poor coordination and underestimating the enemy. The combination of British military prowess and Indigenous tactical skill had handed the U.S. one of its worst defeats.

The Failed Invasion of Canada Forces a Pivot in Strategy

In summary, the American invasion of Canada via Michigan in 1812 fizzled into a full-scale retreat and surrender. General Hull’s cautious tactics, while intended to preserve his army, led to missed opportunities and ultimately a catastrophic capitulation. The British and their First Nations allies exploited every American misstep – from the swift strike at Fort Mackinac, to cutting off Hull’s supplies at Brownstown, to the masterful bluff at Detroit. The outcomes were sobering: an entire U.S. army lost, American territory occupied, and Native coalitions emboldened (albeit temporarily) by significant victories. For the Americans, the campaign’s failure prompted a change in leadership and resolve to retake the initiative. For the British and Canadians, the summer of 1812 was a defensive triumph that ensured the war would drag on rather than be decided on American terms. And for the Indigenous peoples, it was a moment of power and unity – though sadly, one that would later be followed by tragic repercussions once the tides of war turned.

References

The account above is based on historical records and analyses from multiple sources, including official War of 1812 histories and contemporary reports. Notably, William Hull’s invasion plan and retreat are detailed in War Department dispatches and later critiques heritagemississauga.comheritagemississauga.com.

The surprise capture of Fort Mackinac and its effect on Hull is well documented in campaign histories en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

The ambush at Brownstown is described in both American and British accounts, highlighting Tecumseh’s role and the intelligence windfall of captured dispatches battlefields.org.

The evacuation and massacre at Fort Dearborn have been analyzed by historians, with survivors’ testimonies providing harrowing details of the battle’s 15-minute spanen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

General Brock and Tecumseh’s maneuvers at Detroit, as well as Hull’s surrender, are recorded in official correspondence and later summarized by historians en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

The immediate aftermath – including Harrison’s appointment – is noted in U.S. Army chronicles of the war en.wikipedia.org.

Together, these sources paint a comprehensive picture of a dramatic campaign that, in a span of weeks, changed the course of the war in the Northwest.