Newaygo, Michigan, nestled along the steady current of the Muskegon River, carries a long and dramatic history. Its story spans centuries of change, from Native American settlements to booming industry, destructive fires, and bold reinvention. Between 1880 and 1940, Newaygo experienced multiple transformations that reshaped its economy and its identity.

Video – Newaygo Michigan History: 7 Stunning Events That Transformed This River Town

The River Before Settlement

Long before European settlers arrived, Native American tribes called this region home. The Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi lived along the rivers, using the Muskegon as a transportation and trade route. French explorers and fur traders paddled through the area as early as the 1600s. The river was a highway for trade, migration, and culture long before it carried logs or powered dams.

Newaygo itself likely takes its name from Chief Nuwagon, an Ojibwe leader who signed the Treaty of Saginaw in 1819. Some historians suggest it may also come from an Algonquian word meaning “much water” — fitting for a town tied so closely to its river.

Lumber Brings the First Boom

In 1836, John Brooks arrived, drawn by the towering white pines that dominated the land. He began harvesting lumber and soon became Newaygo’s first postmaster in 1847. The Penoyer family followed, building the Big Red Mill — the town’s first sawmill — on the river’s east bank.

As the lumber boom grew, the Muskegon River became a log highway, floating massive rafts of timber downstream to Muskegon and then on to Chicago. Much of Newaygo’s lumber was used to help rebuild Chicago after its Great Fire of 1871. The railroad’s arrival in 1873 connected Newaygo directly to Grand Rapids, Detroit, and Chicago, further accelerating the town’s growth.

By 1880, Newaygo was a thriving lumber town. Its population swelled as workers arrived to cut timber, load railcars, and work the mills.

The Fire of 1883 Nearly Ends It All

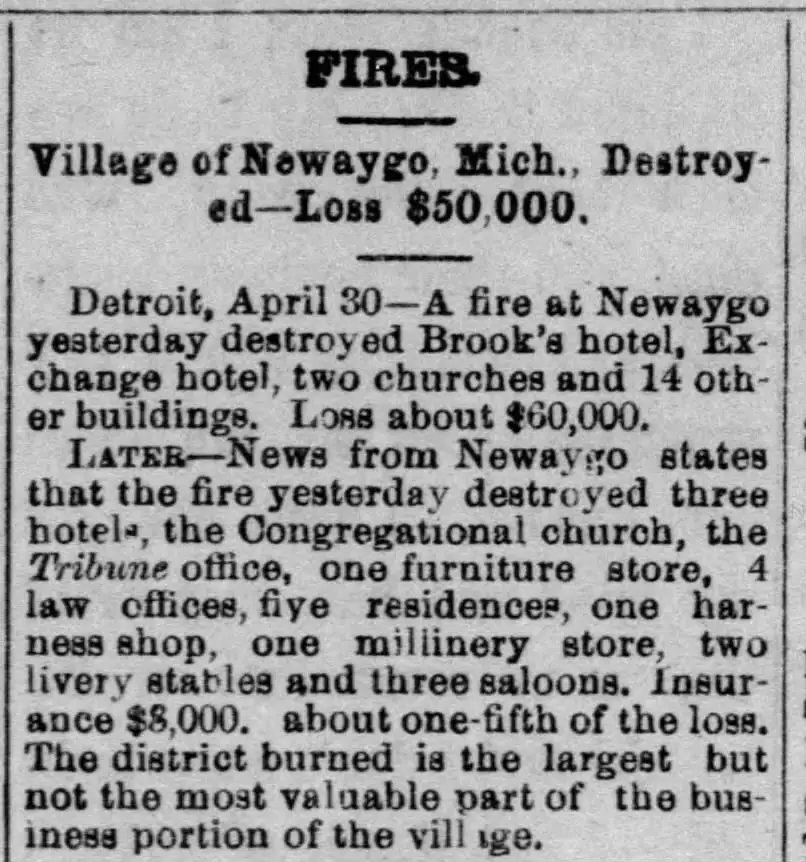

Prosperity turned to disaster in 1883. A massive fire swept through Newaygo’s downtown, consuming nearly every building in its path. Only two structures survived. The town was nearly wiped off the map.

But Newaygo’s residents rebuilt. This time, they constructed brick buildings in the popular Victorian architectural style. The fire had taught hard lessons about the dangers of wooden structures in a town built for lumber. The newly rebuilt downtown set the visual character that remains recognizable today.

Farming and Cement Replace Logging

By the late 1880s, the great pine forests were nearly exhausted. The logging boom faded, and many lumbermen moved on. In their place came farmers, who cleared the remaining land for crops. But beneath those fields lay another resource: marl.

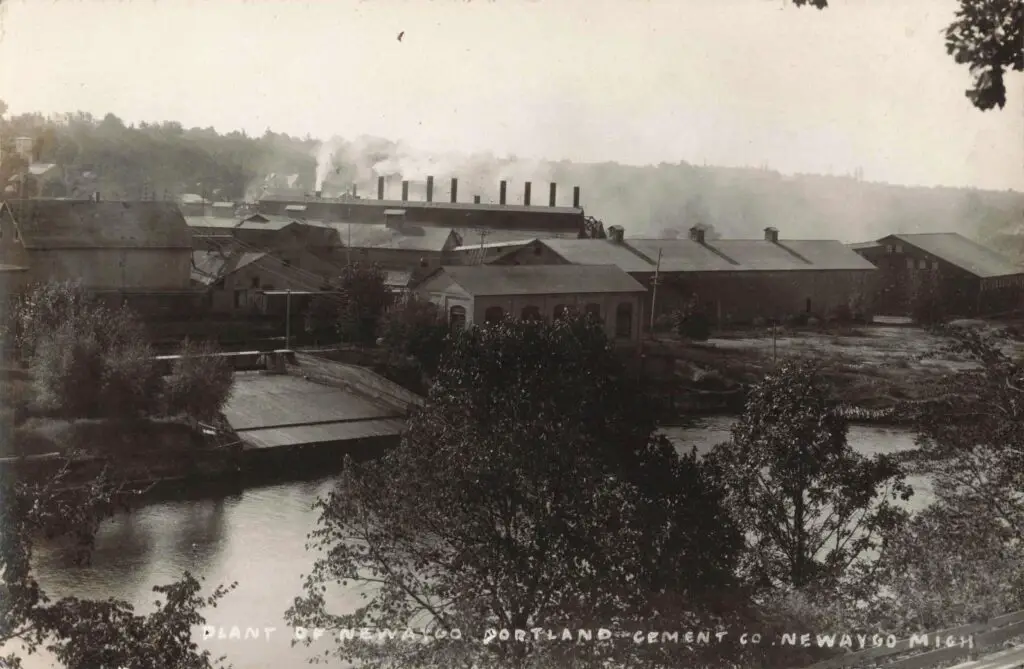

In 1899, the Newaygo Portland Cement Company formed, tapping rich deposits of marl to produce Portland cement. The plant’s twin smokestacks became a prominent feature of the town’s skyline. Cement barrels left town by rail, supporting construction projects throughout the Midwest.

The cement industry carried Newaygo through the early 20th century. Alongside farming, it provided stable employment and kept the town growing even as the lumber camps disappeared.

The River Powers a New Industry

Newaygo’s river wasn’t finished shaping its future. In 1907, the Croton Dam was completed a few miles upstream. It provided hydroelectric power at a time when rural electrification was still rare. Hardy Dam followed in 1931, briefly becoming the tallest earthen dam in the world.

The dams not only provided electricity but also brought steady jobs during the Great Depression. Construction work, ongoing maintenance, and growing recreation around the new reservoirs helped Newaygo weather tough economic times.

The Muskegon River had carried logs for decades. Now it carried power — both literally and economically — into the future.

Tourism Emerges as Nature Returns

As forests regrew, Newaygo found new life as a destination for outdoor recreation. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, planted trees, built trails, and helped restore the region’s natural beauty. In 1938, thousands of acres were incorporated into Manistee National Forest.

Tourists arrived for fishing, boating, and quiet escapes. Resorts like Sholtey’s Lake Resort welcomed visitors eager to enjoy the water, fresh air, and growing network of cabins and campsites. The suspension footbridge, the bustling canoe docks, and scenic riverbanks became symbols of a town once again reinventing itself.

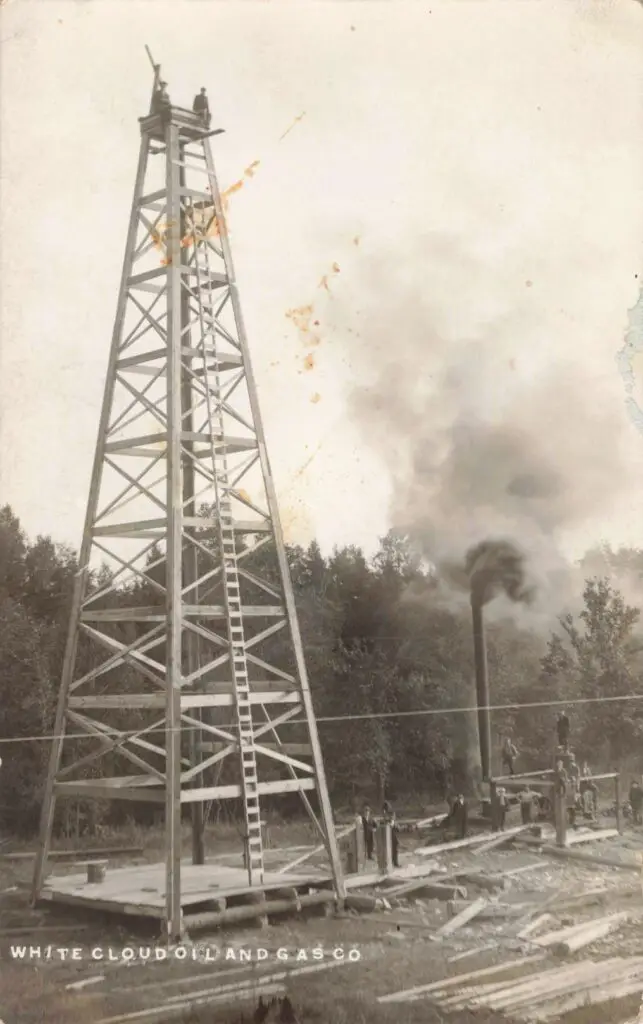

Oil Drilling Sparks New Hopes

By the late 1930s, yet another chapter began. Exploratory oil drilling rigs appeared across Newaygo’s farmlands. While not every well produced, the prospect of oil brought new optimism for economic growth.

The sight of tall drilling towers and the buzz of machinery in open fields marked the town’s growing diversification. Newaygo was no longer just a lumber town, a cement town, or a farm town. It was all of these — and more.

Newaygo’s Enduring Story

By 1940, Newaygo’s population had steadied, reflecting its stable mix of agriculture, industry, and tourism. Its economy rested on a balance of cement, farming, hydropower, and recreation. The town had faced fire, economic shifts, and environmental change but endured through each transformation.

At the heart of it all remained the Muskegon River — once a lumber highway, later a source of power, and always the steady thread connecting each chapter of Newaygo Michigan history.