At the start of the 20th century, Menominee, Michigan was a town in the midst of great change. Situated at the mouth of the Menominee River on Lake Michigan’s Green Bay, Menominee had risen to fame as a lumber boomtown in the late 1800s. In fact, Menominee produced more lumber than any other U.S. city during its peak years. Menominee Michigan history comes alive through rare 1900–1950 photos: log drives, streetcars, herring boats, factories, and concerts by the bay that shaped a Great Lakes city.

Menominee Michigan History – Table of Contents

Video – History of Menominee Michigan: Rare Photos That Show Its Rise and Revival

Menominee’s Lumber Hertiage

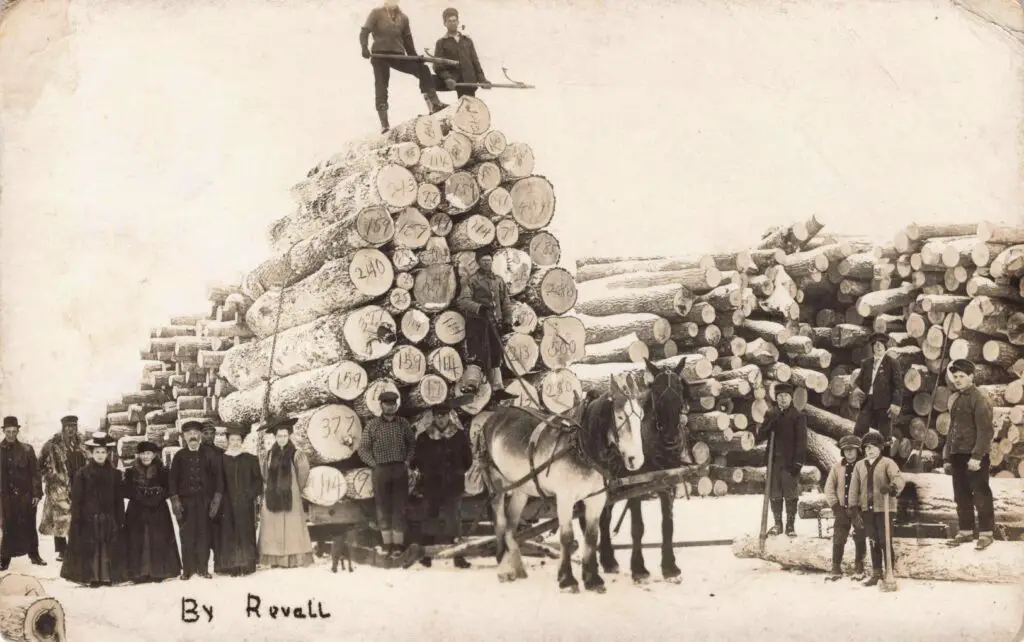

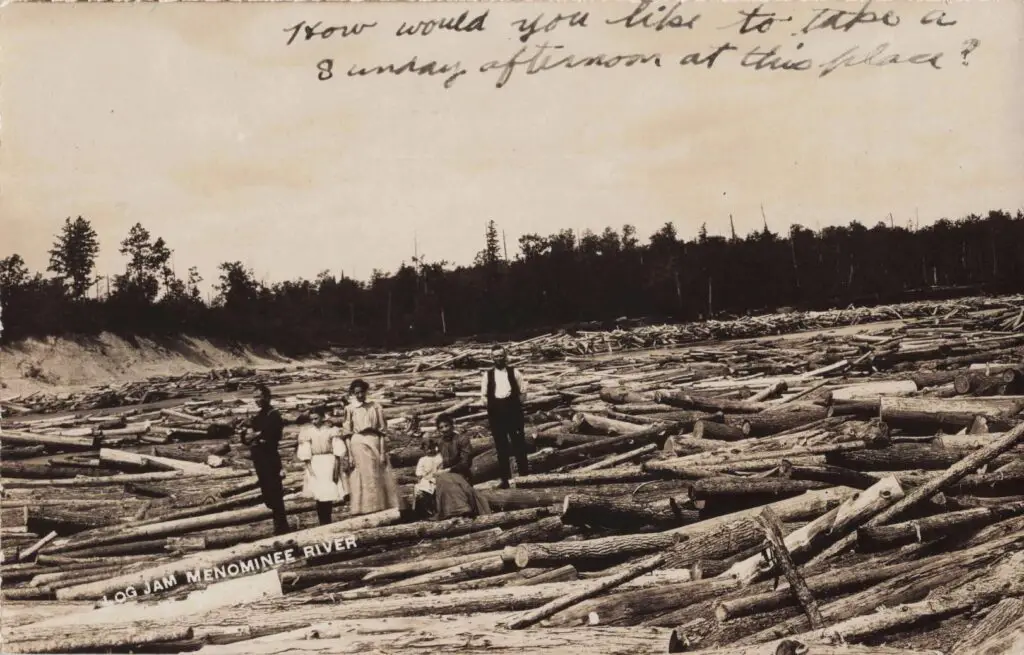

The Menominee River Boom Company, formed in 1866, sorted and drove millions of logs downriver to local sawmills. In 1899 alone, the Boom Company processed over 4.25 million logs, briefly making Menominee “the largest lumber shipping port in the world.”

The riverside was a sight to behold – huge log jams often filled the water near Menominee and its Wisconsin twin city, Marinette. To manage this flow, the company built 44 logging dams on the Menominee River and its tributaries, using spillways (chutes) to send logs downstream in controlled torrents. Lumber fueled Menominee’s early prosperity, but as timber supplies dwindled by 1910, the city’s leaders faced an uncertain future.

Menominee’s story from 1900 to 1950 is one of adaptation and reinvention.

When the old-growth white pine forests were largely exhausted – the last big log drive came in 1917– Menominee refused to fade away. Instead, the community rallied to attract new industries and make use of its strategic location.

Menominee River Sugar Company

In 1903, local investors established the Menominee River Sugar Company, constructing a large beet sugar refinery on the riverbank. They believed the Menominee River, once a highway for logs, could just as easily float tons of sugar beets and provide abundant water for processing. The resulting factory was one of the most modern of its kind, intended to keep Menominee’s economy strong after lumbering.

Lloyd Manufacturing Company

Around the same time, Marshall Burns Lloyd, an inventor and entrepreneur, arrived from Minneapolis with a bold idea. In 1907, Lloyd set up the Lloyd Manufacturing Company on Menominee’s waterfront to produce wicker baby carriages. He brought his machinery and skilled workers, instantly diversifying the city’s industrial base.

Lloyd’s impact was profound: in 1917 he invented the Lloyd Loom, an automated weaving machine that could create a baby carriage’s wicker body in 18 minutes instead of the 9 hours it took by hand. This innovation turned Menominee into a world leader in wicker furniture production, with Lloyd’s factory employing hundreds of local residents and shipping baby buggies worldwide.

Dam on Menominee River near Ingalls

By the 1910s, Menominee had effectively pivoted from “timber to factory.” The economic base now included sugar refining, furniture manufacturing, paper production, and more. The twin cities of Menominee and Marinette leveraged the river that once carried logs to now power paper mills and hydro-electric dams. Menominee’s location remained a great asset. It had water, rail, and later highway connections that allowed local businesses to bring in raw materials and ship out finished goods efficiently.

Menominee Rail Depot

Railroads were especially crucial in this era. Menominee was served by the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway (CM&StP) – often called the Milwaukee Road – which linked the Upper Peninsula with Milwaukee and Chicago. The city’s CM&StP rail depot (shown in the image above) was a handsome brick station bustling with travelers and freight. Trains carried Menominee’s lumber (and later furniture, sugar, and fish) to distant markets, and brought tourists or new residents into town.

Menominee was also uniquely connected to Michigan’s Lower Peninsula by rail car ferries. Starting in 1894, the Ann Arbor Railroad operated ferries that loaded entire train cars in Frankfort, MI and floated them across Lake Michigan to Menominee. This meant that Menominee effectively sat on a transcontinental rail corridor – one could ship a railcar from Detroit to Menominee by water, then onward by rail to the West. Such connectivity was a huge advantage for a small city.

Menominee Streetcar System

On the city streets, transportation was evolving as well. Menominee and Marinette developed a streetcar system in the late 19th century, originally with horse-drawn cars and soon electrified. In 1903 the local electric railway companies merged into the Menominee & Marinette Light and Traction Company, which ran streetcars across the state line. Streetcars rattled through downtown Menominee and over the Interstate Bridge into Wisconsin, providing affordable transit for workers and shoppers. For a nickel, you could ride from Menominee’s 1st Street shopping district over to Marinette’s neighborhoods.

This system operated until 1928, when rising costs and the need to rebuild the bridge forced the company to shut down and switch to buses. Photographs from the 1910s and 20s capture the charm of those days: in one, a streetcar is seen snowbound after a blizzard, with a dozen men shoveling furiously to free it (winters in Menominee have always been serious business!). After 1928, buses and private automobiles took over urban transport, and the old street railway tracks were eventually paved over.

Downtown commerce in the early 20th century was thriving

The Hotel Menominee (originally built in 1881 by Samuel M. Stephenson) stood as an elegant four-story landmark on Main Street. It hosted businessmen, lumber scouts, and even the occasional VIP – for example, Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks visited Menominee in 1908 and was feted at this hotel (a sign of the city’s prominence at the time).

Along First Street, one could find the Ludington Bros. dry goods store, pharmacies, clothiers, and the Menominee Drug Company in operation. There was also the grand Menominee Opera House, opened in 1902, which boasted 1,000 seats and regularly hosted touring Broadway shows, musical acts, and civic events. Renowned figures like actress Maude Adams and bandleader John Philip Sousa graced the Opera House stage in its prime. This theater was said to be the finest north of Milwaukee when built. Though the Opera’s popularity declined with the rise of cinema in the 1920s and it was repurposed and later damaged by fire in 1950, the building still stands today and efforts to restore it continue, reflecting the community’s pride in its heritage.

Henes Park

Beyond business and industry, Menominee embraced recreation and civic improvement, especially as the decades progressed. An important chapter in Menominee’s history was the development of parks and tourist amenities during the 1920s and 30s. Recognizing that the area’s natural beauty could attract visitors, Menominee’s leaders and the State of Michigan invested in facilities to promote tourism. A key figure was John Henes, a successful Menominee brewer and businessman.

Poplar Point

In 1906 Henes secretly bought a 40-acre wooded peninsula on Green Bay known as Poplar Point. He then surprised the city by donating this land in 1907 to create Henes Park, a public park and bathing beach for all to enjoy. Henes Park was professionally designed by a landscape architect and included picnic areas, walking trails named after poets, and a pristine natural beach. It quickly became (and remains) Menominee’s favorite spot for outdoor fun – a true gift to the people.

Menominee Bandshell

Fast forward to the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when federal programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were helping communities with infrastructure projects. Menominee benefited greatly: in 1932 a new breakwater and municipal marina were built on the waterfront as a WPA project. This created a safe harbor for boats and helped prevent shoreline erosion. That same year, Menominee constructed a beautiful Bandshell at the edge of the new Marina Park.

Designed by local architect Derrick Hubert, the Menominee Bandshell had a dual purpose – it was an open-air concert stage facing the park lawn, and it also housed the Marinette-Menominee (M&M) Yacht Club’s clubhouse facilities in the back rooms. The bandshell was built in a sleek Art Deco style (popular at the time, even in the U.P.) and was immediately embraced as a cultural centerpiece. Summer band concerts and community events were held at the bandshell every year.

One annual tradition that evolved was Menominee’s Waterfront Festival, with the bandshell hosting live music as part of the festivities. Impressively, the Menominee Bandshell still stands today – it was restored in recent years and continues to host concerts, art shows, and festivals, making it a lovely continuity between past and present.

Michigan State Highway Tourist Lodges

Another Depression-era initiative was the concept of Tourist Lodges or welcome centers. Michigan’s highway commissioner, Murray D. Van Wagoner, pioneered the idea of building roadside tourist information cabins to greet travelers entering the state. Menominee was chosen as the site for one of the first such lodges (after an initial one at New Buffalo downstate). In 1936–37, using local labor (including Civilian Conservation Corps workers), the state built the Menominee Tourist Lodge right near the Interstate Bridge from Marinette. This rustic log cabin structure had a stone fireplace, brochures and maps on display, and staff to answer questions – a precursor to today’s highway rest areas and welcome centers.

It opened in July 1937 and was touted as possibly the oldest continuously operating travel information center in the U.S. today. The Tourist Lodge’s design was intentionally quaint: built with Scandinavian-style “chinkless” log construction, using local red pine logs, with a copper roof and fieldstone chimney, it exuded Upper Peninsula charm. Travelers from Chicago or Milwaukee heading up U.S. Highway 41 would cross into Michigan and immediately be greeted by this friendly cabin offering coffee and travel tips. The Menominee Tourist Lodge symbolized the city’s shift to welcoming tourists as a complement to industry. Remarkably, after 85+ years (with some rebuilding in the early 1980s due to log deterioration), the lodge still serves as the Menominee Welcome Center, greeting visitors to the U.P. with its warm, woodsy atmosphere.

Dormer Company Fish Plant

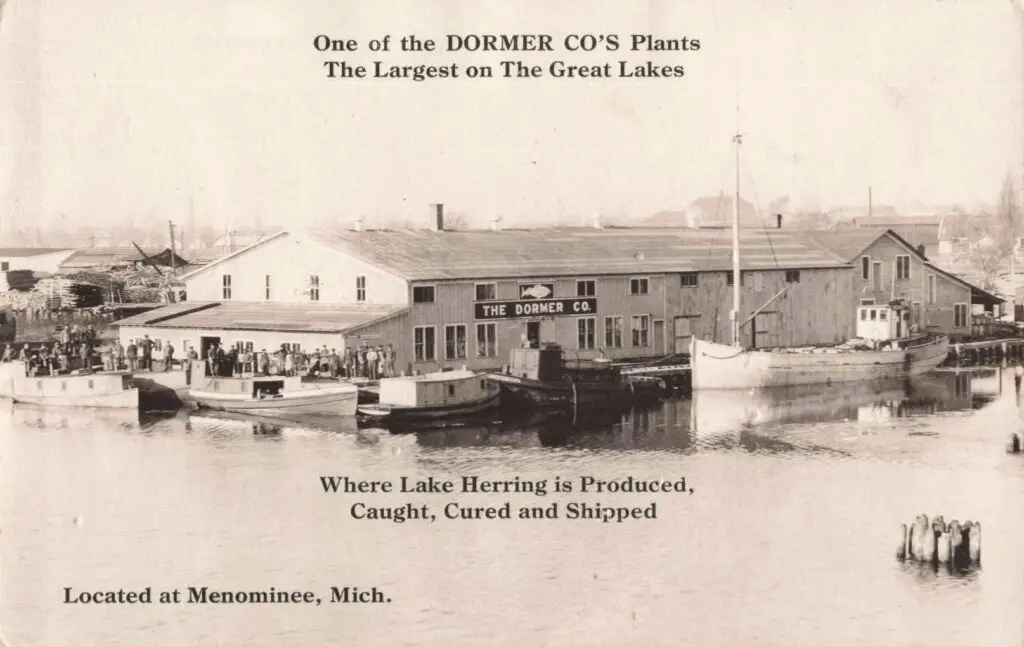

No history of Menominee from 1900–1950 would be complete without mentioning the city’s fishing industry and maritime culture. Besides lumber, one of the oldest economic activities in Menominee was commercial fishing in the rich waters of Green Bay. Families of fishermen, often of Scandinavian and French-Canadian heritage, ran fishing tugs out of Menominee’s harbor for generations. They harvested whitefish, lake trout, perch, chubs, and especially lake herring (often locally called “Cisco”).

Dormer Company became a big name in this trade. Founded by James Dormer in the late 19th century, by the 1920s the Dormer Co. operated multiple fish packing plants in the area. One 1924 postcard proudly proclaims Dormer’s Menominee facility as “The Largest on the Great Lakes where Lake Herring is caught, cured and shipped”. The company had been “60 years at the game” by then (meaning since the 1860s). Menominee’s location was ideal – fishermen could quickly reach spawning grounds, and the cold climate was helpful for preserving fish.

Tons of salted or iced Menominee herring were loaded onto refrigerated rail cars bound for markets in Chicago and the East Coast. Green Bay perch was another local specialty, often shipped fresh for Friday fish fries in Midwest cities. The Menominee fishing fleet, combined with Marinette’s, was substantial. However, by the late 1940s and 1950s, the Great Lakes fishery faced a dire threat: the invasion of the sea lamprey eel, which decimated trout and herring populations after sneaking in through navigation canals. The local fishing industry went into decline mid-century due to these ecological changes (and later pollution), but in the first half of the 20th century it was a cornerstone of Menominee’s livelihood.

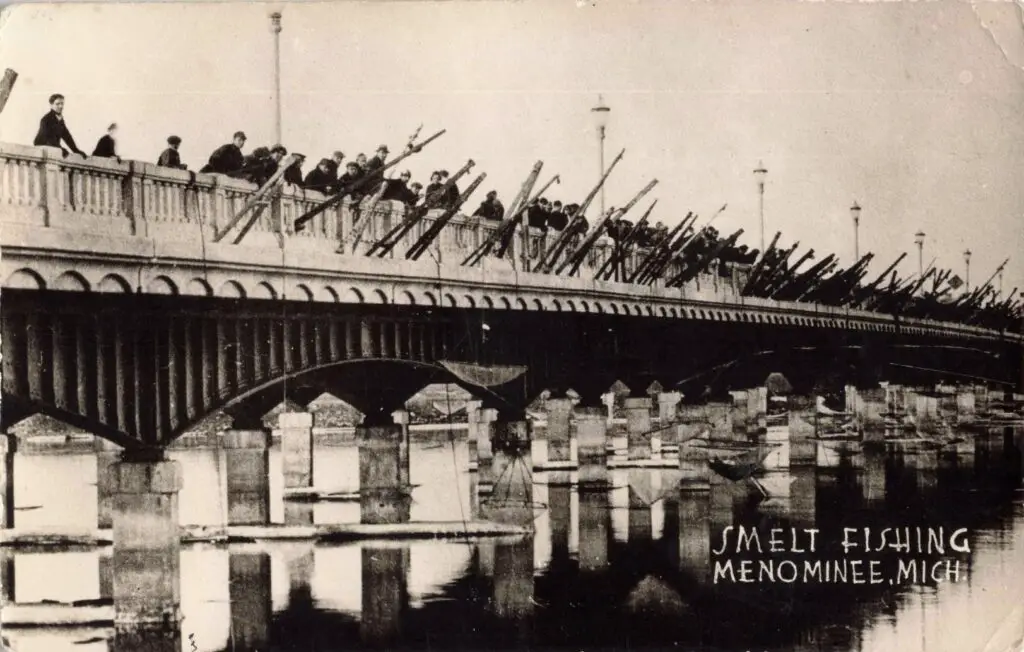

Menominee’s Culture of Smelt Fishing and Dipping

In spring, when water temperatures warmed in the Menominee River and its tributaries, something remarkable happened: the smelt run. Smelt, a small silvery fish not native to the Great Lakes but well-established there by the early 20th century, would swim upstream to spawn. For the people of Menominee and Marinette, those runs were not just a commercial opportunity—they were a seasonal ritual. Families and community members would gather on riverbanks or standing bridges in the dark, using dip nets to scoop fish out of the water. Flashlights, lanterns, and sometimes bonfires would light the scene. Boats might be used too, with nets trailing behind. In some years, the volume of fish was so great that smelt dipping became a festival, with laughter, competition, and shared meals—fried smelt cooked immediately, fresh from the run.

The tradition had both economic and social value. Some catches were sold or traded; many were eaten locally as part of communal meals. Smelt fishing bridged generations: elders taught young people where to stand, how to use the net, how to watch for signs—a change in water clarity, or a sudden swirl in the current. The events often centered on bridges or shallow river mouths, places where fish would concentrate. Over time, as fish populations fluctuated due to environmental changes and other pressures, the runs sometimes waned. But to many in Menominee, smelt dipping remained something they looked forward to each spring—a marker of seasonal shift, a chance to gather, eat, and celebrate together by the water.

St. Joseph’s Hospital in Menominee

Throughout Menominee Michigan history, these economic ebbs and flows, Menominee also fostered a strong sense of community and civic institutions. We’ve mentioned the Opera House and library as cultural landmarks. Another pillar was healthcare. In 1891, the Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis established St. Joseph’s Hospital in Menominee. Starting as a small maternity and general hospital, St. Joe’s grew with the community – an addition in 1911 expanded its capacity.

The hospital served not just Menominee but also Marinette; in effect it was a regional hospital for the twin cities (even today, Menominee and Marinette share a hospital system). In 1950, a new wing called Marshall Lloyd Memorial (Lloyd Hospital) was opened adjacent to St. Joseph’s. Marshall Lloyd had passed away in 1927, but his legacy and family’s philanthropy lived on in this modern medical facility. For many decades, St. Joseph’s (later called Menominee General) was where local families were born and cared for – a testament to the city’s dedication to its people’s well-being.

Gracie Allen for Menominee Mayor

Finally, a charming anecdote from Menominee Michigan History is that during the 1940s highlights the town’s ability to have a little fun even in serious times. In 1940, with war looming in Europe, the popular radio comedians George Burns and Gracie Allen ran a mock presidential campaign for Gracie as a publicity stunt. Menominee got swept up in the whimsy when some residents nominated Gracie Allen for Mayor of Menominee.

The city actually took the nomination semi-seriously until they regretfully concluded Gracie was ineligible (since she wasn’t a Menominee resident). The whole affair brought national attention and comic relief to Menominee – even getting mentioned in newsreels – and it showed that this small industrial city had a hearty sense of humor and civic identity.

By 1950, Menominee had navigated 50 years of dramatic change

The population in 1950 was about 11,000, slightly higher than it had been in 1900. Remarkably, Menominee had avoided the fate of many former boomtowns that became ghost towns. Instead, it reinvented itself multiple times. The foundation was laid for the modern Menominee: an economy based on manufacturing (from paper products to boat building to wicker furniture) and a growing emphasis on tourism and cross-border regionalism.

Many of the early 20th-century landmarks have survived into the present, giving Menominee a distinctive historic charm. The downtown historic district still contains 19th-century and early 20th-century buildings like the Menominee County Courthouse (1875), the Spies Public Library (1904), and the First National Bank building (c.1900).

The Marina and Bandshell are still focal points of civic life, hosting events like the annual Marina Festival and weekly summer concerts. The Menominee North Pier Lighthouse, rebuilt in 1927 to guide ships into the harbor, still shines every night, symbolizing the city’s enduring connection to the Great Lakes. And importantly, the spirit of cooperation with Marinette – its twin across the river – remains strong. The two communities share a newspaper (the EagleHerald), a hospital system, and many social and economic ties, a legacy of over a century of growing together.

Menominee Michigan History from 1900–1950 is a vivid example of a small American city’s resilience and ingenuity. From the pine forests to the factory floor, from schooners and steam trains to highways and tourists, Menominee constantly adapted to the changing times. The people took pride in their city – building parks, hospitals, and cultural venues even when times were tough – and that pride is evident in Menominee’s well-preserved heritage.

Visiting Menominee today, one can stroll along the same riverfront where logs once bobbed, enjoy a concert at the historic bandshell, and perhaps chat with a descendant of a lumberjack, a fisherman, or a Lloyd factory worker. The past is very much present here. Menominee may be off the beaten path, the southernmost city in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, but its story of innovation, community, and survival in the first half of the 20th century is as rich as any in Midwest history.

Sources Consulted and Utilized In Menominee Michigan History

“Back in the Day — Smelt Runs Were Cause to Celebrate.” Wisconsin Natural Resources Magazine, Spring 2019.

“Former Plant of Menominee River Brewing Co. … Herring Packed by the Dormer Company.” Menominee Herald-Leader, 13 Nov. 1922, p. 8.

GILL-NET TUG KATE: A Great Lakes Fisheries Heritage. Library of Congress / National Park Service, ca. 2019.

“Iconic Cabin Still Welcomes Tourists to the U.P.” UPword Michigan.

“About — Company Timeline.” Lloyd Flanders.

A Profile of American Tradition, Innovation, and Quality: Lloyd Flanders Company History. Lloyd Flanders.

“Menominee Michigan: Historical Tidbits (Part 2, 1900–1928).” Letters for George, 18 Mar. 2014.

“Menominee North Pier Lighthouse.” U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office, 17 Sept. 2019.

“Menominee North Pier Lighthouse.” Menominee County Historical Society.

“Menominee North Pier Light Station.” Pure Michigan.

“The Menominee Opera House.” Menominee County Historical Society.

“About — History.” Menominee Opera House.

“Menominee Welcome Center.” Michigan Department of Transportation.

“Menominee Welcome Center Celebrating 85th Year of Serving Tourists.” Radio Results Network, 10 Jan. 2023.

“One of the Dormer Co.’s Plants — Menominee, Mich. (1924).” University of Michigan Library — Real Photo Postcards (Tinder Collection).

“Spies Public Library.” SAH Archipedia.

“Spies Public Library — Library History.” Spies Public Library.

“Smelt Runs.” Loukinen, Dan. Letters for George, 3 Apr. 2012.

“Dipping Smelt (Menominee River, Apr. 16, 1938).” UW–Madison Digital Collections.

“Lloyd Loom.” Wikipedia.

“Interstate Bridge (Marinette, Wisconsin – Menominee, Michigan).” Wikipedia.

“Transit Systems in Michigan — Menominee & Marinette Light & Traction Co.” ChicagoRailfan.com.

“Menominee and Marinette Light and Traction Company (E).” MichiganRailroads.com.