Grand Beach, Michigan, once rivaled bigger resorts with its white-sand beach, dance pavilion, and the Grand Hotel Golfmore. Only sixty-five miles from Chicago, the hotel resort offered golf, trail riding, and sugary sand beaches of Lake Michigan. This history of Grand Beach, Michigan, traces the village’s rise, Jazz Age summers, and the 1939 fire that erased its famous hotel.

Table of Contents

Video – Hotel Golfmore – Grand Beach Michigan’s Huge Resort That Went Up in Smoke

Founding of Grand Beach as a Resort Village (Early 1900s)

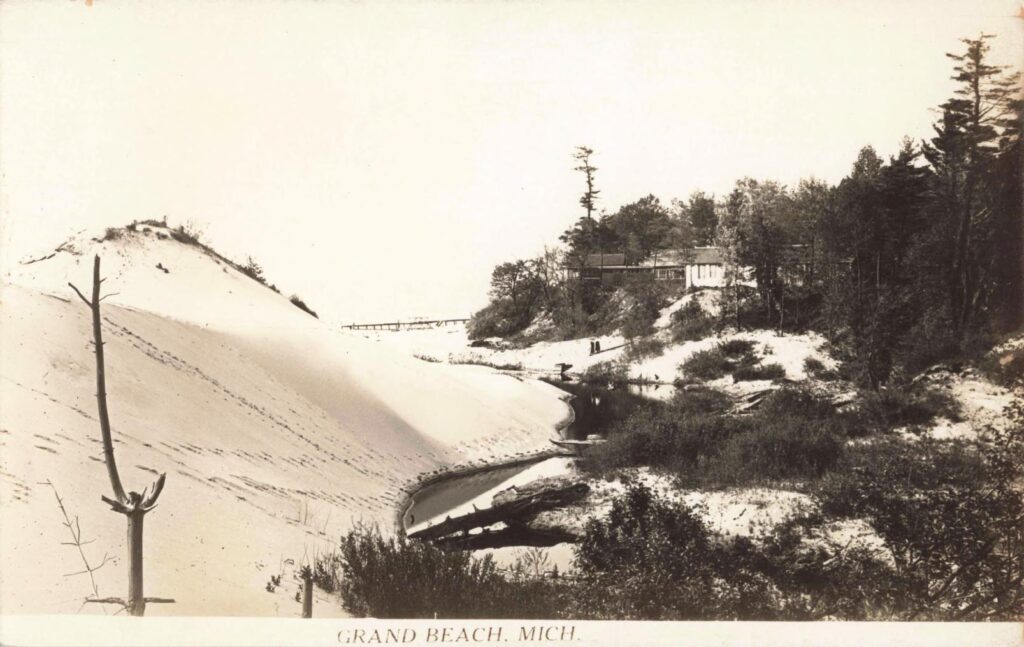

Grand Beach began as an undeveloped stretch of dunes and pristine Lake Michigan shoreline in the late 19th century. In 1903, Chicago entrepreneur Floyd R. Perkins (an advertising man) saw the potential of this lakeside wilderness. He initially purchased 600 acres for a private hunting retreat but soon shifted his focus to creating a resort community. Together with partner George Ely, Perkins formed the Grand Beach Company and acquired approximately 4 miles of beachfront. Over the next few years, they laid out basic infrastructure – roads, bridges, a water works, and a nine-hole golf course – anticipating an influx of leisure tourists. The name “Grand Beach” itself was coined by Perkins, referring to the broad expanse of fine white sand along the lakeshore.

By 1907, development accelerated when the company ordered 20 prefabricated cottages from Sears, Roebuck & Co., quickly creating lodging for visitors. These simple rental cottages were placed amid the woods and dunes. By 1911, the village boasted around 48 cottages in total, clustered near the lake and golf links. Grand Beach was conceived as a short-stay resort destination – a place where families from Chicago or South Bend could come for a weekend or summer week to enjoy nature’s serenity. In 1934, the community would formally incorporate as the Village of Grand Beach, solidifying local control, but its character was set in those early years.

Early amenities and recreation. From the outset, Grand Beach offered a blend of relaxation and recreation. The beach itself was the prime attraction – a three-mile stretch of clean, broad sand for sunbathing and swimming.

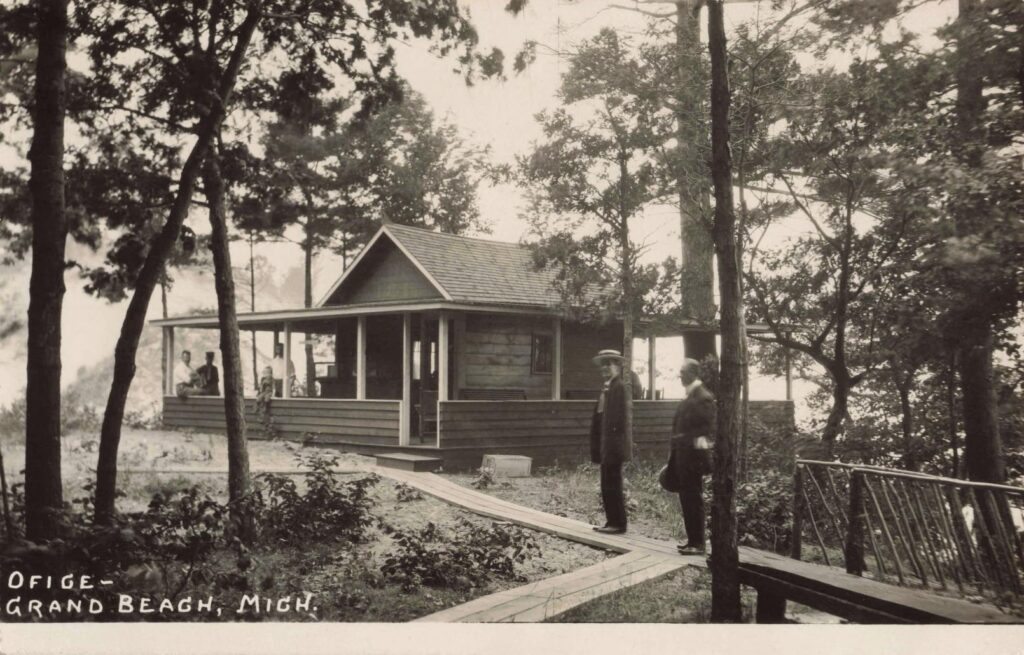

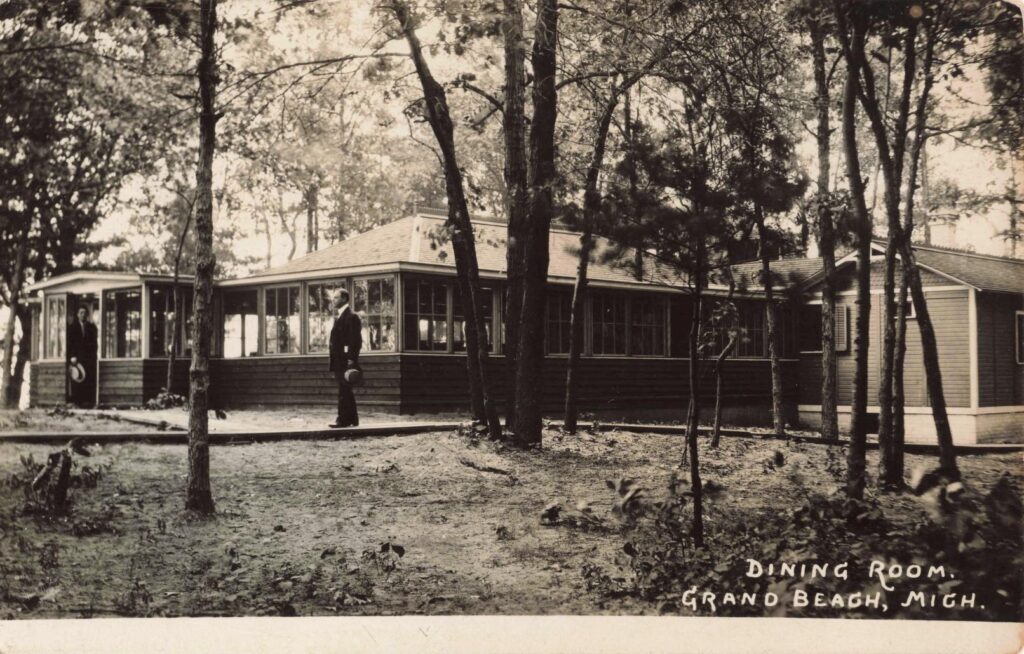

The Grand Beach Company built a rustic “clubhouse” or dining hall near the lake where guests could get meals and refreshments. This dining hall (located at Lakeview and Whitewood Avenue) doubled as a social hub, where one might sip a cold drink or enjoy a “quiet repast among the dunes” in the shade. For those inclined to amusements, there was even a small casino on the grounds – not a Las Vegas-style casino, but a room for informal gambling and games where visitors could try their luck.

The nine-hole golf course, carefully manicured, gave the resort its sporting appeal; guests could play a round or two with vistas of the dunes. As demand grew, the course was later expanded to a full 18 holes by the late 1910s, and eventually to a 27-hole layout by the 1920s to accommodate the resort’s popularity.

Every summer, families would return to Grand Beach to enjoy these simple pleasures: bathing in the lake, golfing, fishing for minnows (“catchin’ minnies” as one whimsical postcard called it), and strolling under the canopy of old-growth trees along sandy paths and footbridges. In the evenings, kerosene lanterns and later electric lights would glow from the cottages and the central pavilion, as visitors gathered to socialize after a day of sun and sport.

Timeline of Key Developments (1903–1930):

- 1903: Grand Beach Company was founded by Floyd R. Perkins and George Ely; 600 acres of dunes were purchased to develop a resort.

- 1905–1907: Initial infrastructure completed – roads, water system, and a 9-hole golf course. First wave of cottages built, including 20 Sears kit cottages in 1907.

- 1911: Resort thriving with ~50 cottages, a Michigan Central Railroad stop just outside the gates, and steady tourist arrivals. The signature white entry archway is in place by this time.

- 1916: Notable architecture – three Frank Lloyd Wright-designed summer cottages are built in Grand Beach (e.g. the Ernest Vosburgh house), reflecting the resort’s popularity among affluent Chicagoans.

- 1921–1922: Hotel Golfmore constructed (just across the nearby creek in Michiana); opens as a grand luxury hotel with 175 rooms. The golf course is enlarged to 27 holes, and a footbridge links the hotel to Grand Beach.

- Early 1920s: A lakefront entertainment pier and dance pavilion are built jutting into Lake Michigan, offering dining and dancing over the water. Grand Beach’s “Grand Central” train station and new Dunes Highway (US 12) bring increasing crowds.

- 1926: Winter sports arrive – a ski jump exhibition and competition (featuring Olympic jumper Anders Haugen) is held on the dunes, hosted by the Hotel Golfmore.

- Late 1920s: Peak of the resort’s golden era – hundreds of tourists flock on weekends by car and train; social events, golf tournaments, beach parties, and nightly dances are common.

- 1929–1930: The onset of the Great Depression begins to temper the exuberance. Even so, many who can afford it continue summering at Grand Beach, though the village’s growth slows. (In 1934, the resort community incorporated as a village, and in 1939, the landmark Hotel Golfmore tragically burned down, marking the end of an era.)

Transportation, “Grand Central” Station and Tourism Networks

A real-photo postcard (postmarked 1911) of the quaint “Grand Central Station” at Grand Beach. This small depot on the Michigan Central line was the drop-off point for resort-goers arriving by train.

In the early 20th century, reaching Grand Beach was half the adventure. Railroads were the essential link for travelers before automobiles became commonplace. The Michigan Central Railroad ran along the southwest Michigan coast, and the Grand Beach Company arranged for trains to stop at a little station just outside the resort’s gates.

With tongue-in-cheek humor, this modest stop was nicknamed “Grand Central Station” – a playful reference to New York’s Grand Central Terminal, despite being a simple country depot. For a modest fare, city dwellers from Chicago could board a Michigan Central train and, in a couple of hours, step off at Grand Beach, immediately breathing the pine-scented air and cool lake breezes. They would then pass through the whitewashed arched gateway into the resort, walking or taking a jitney down a pleasant path flanked by the golf course to reach their cottages.

In the 1910s, interurban electric trains also connected nearby towns – for example, the Chicago South Shore & South Bend Railroad (1908) carried passengers as far as Michigan City, Indiana. From Michigan City, Grand Beach-bound guests might transfer to a local train or even hire an automobile for the last leg of the journey. Many visitors also came via Michigan Central’s main line to New Buffalo (just a few miles north), then by carriage or car to Grand Beach. The ease of rail access in this era enabled Grand Beach’s growth as a convenient escape from the city bustle.

By the 1920s, the automobile revolution was in full swing, changing the patterns of tourism. A modern highway – the Dunes Highway (U.S. 12) – was paved in stages by 1922, running along the Indiana shore into Michigan. This new road “was built with tourism in mind” as a gateway to the lake’s southern shore. Now, Chicagoans with Model T Fords or other early cars could drive the ~60-70 miles to Grand Beach in a few hours.

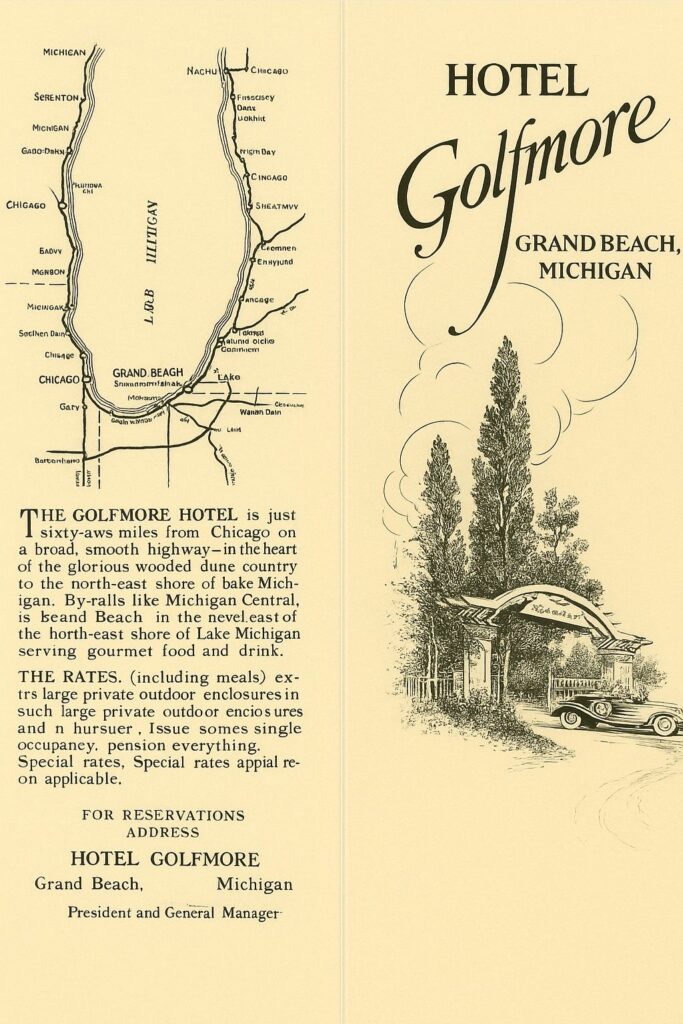

The hotel’s brochure proudly advertised the resort as “just sixty-two miles from Chicago on a broad, smooth highway” through the “glorious wooded dunes country”. As a result, weekend traffic swelled – long convoys of automobiles would wind along U.S. 12 toward the “Gateway of Michigan” (as New Buffalo’s 1928 arch famously proclaimed). Photographs from the late 1920s show Model Ts and touring cars lined up at Grand Beach’s entrance or parked near the beach as “weekend arrivals” poured in. Train service remained important (excursion trains ran hourly on some nearby lines), but families increasingly enjoyed the freedom of driving out to the dunes for vacation.

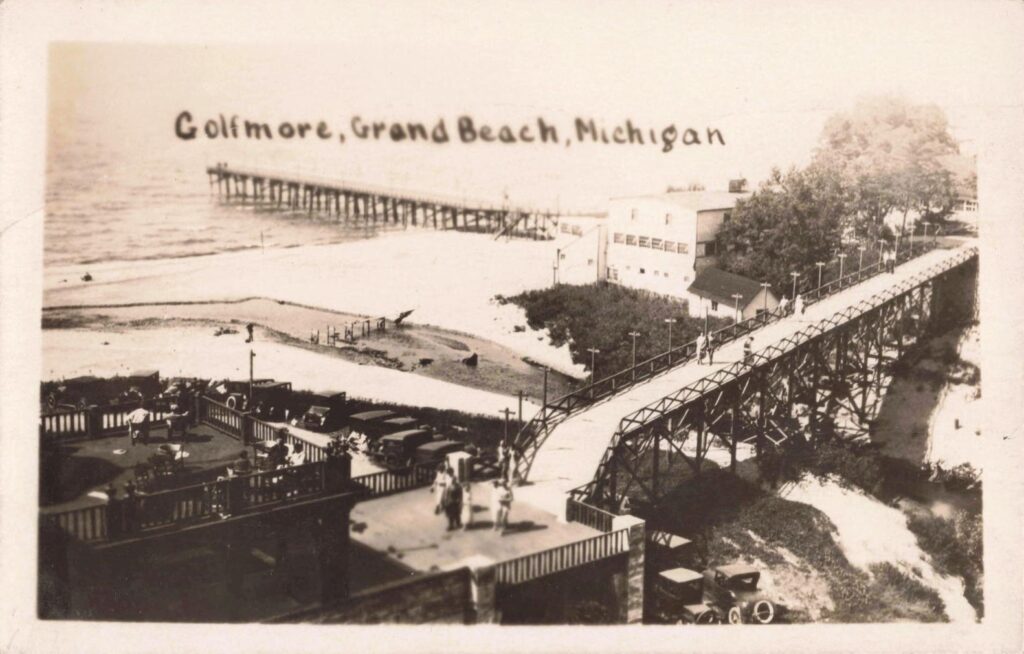

Lake Michigan itself was another transportation avenue. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, fleets of passenger steamers plied the lake, ferrying tourists between Chicago and Michigan’s resort towns. While Grand Beach did not have a large harbor, it did build a pier and boat landing for smaller craft. In the 1920s, an entertainment pier extended out into the lake at Grand Beach, used not only for dancing but also, on calm days, for docking excursion boats or private yachts.

Visitors could watch steamships in the distance or even arrive by lake steamer to nearby Michigan City or St. Joseph, then make their way to Grand Beach. Thus by the 1920s, rail, road, and lake transport all intertwined to bring a steady flow of tourists – from wealthy businessmen to day-tripping families – to this corner of Lake Michigan. The infrastructure investment (train station, good roads, and a pier) paid off as Grand Beach became a bustling vacation community in the summer months.

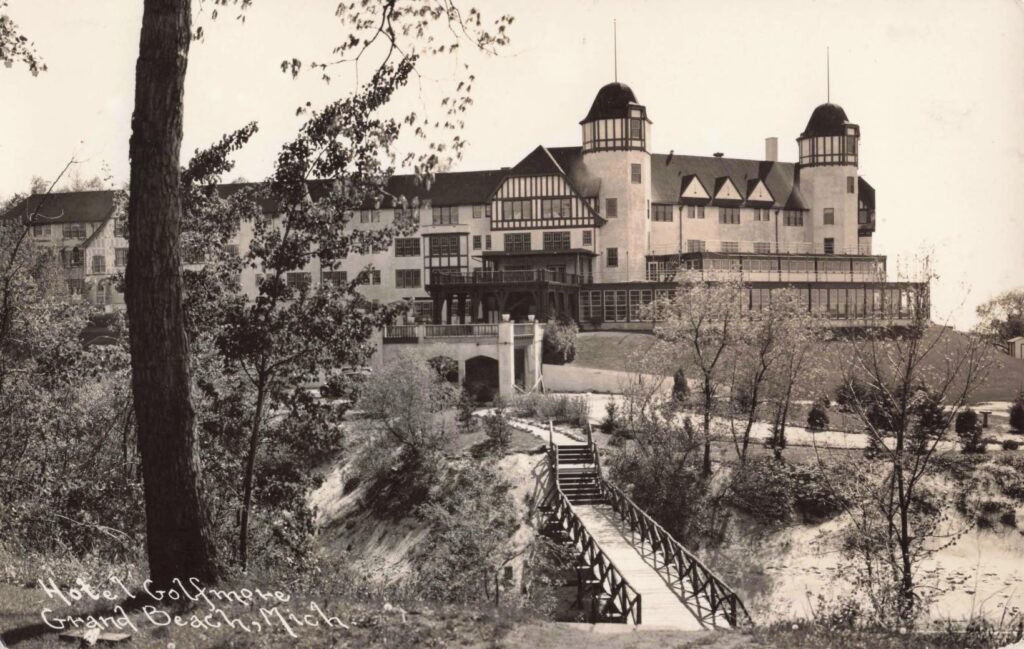

Hotel Golfmore: Construction and Significance (1921–1930)

By the early 1920s, Grand Beach’s success prompted an ambitious project: a grand resort hotel to rival the finest on the Great Lakes. In 1921, construction began on Hotel Golfmore, a luxury hotel that would become the crown jewel of Grand Beach. The chosen site was just across the state line in the adjoining Michiana area of Michigan – immediately south of Grand Beach’s original plat, across a small stream called Spring Creek. (The state boundary between Michigan and Indiana runs near that creek, hence the name “Michiana.”)

A footbridge was built over Spring Creek to seamlessly connect the new hotel’s grounds with the rest of Grand Beach. When Hotel Golfmore opened for guests in 1922, visitors could stroll over the bridge from the beach pavilion straight into the hotel’s lawns and gardens.

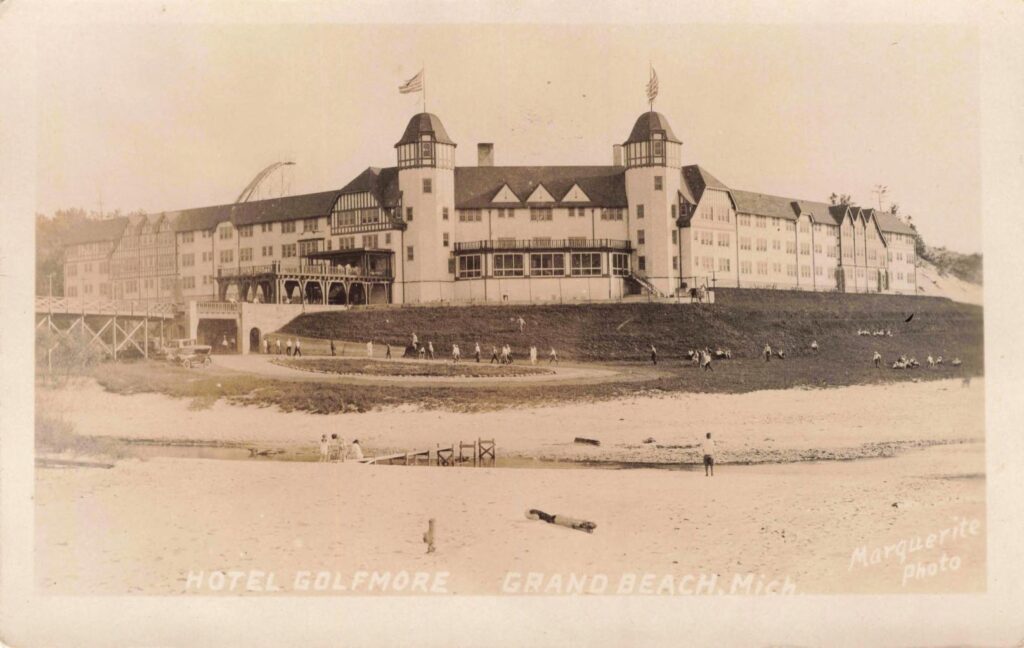

Hotel Golfmore was truly grand in scale and style. Classic resort hotels inspired the design – local lore says it was meant to rival the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, which had been the gold standard for Michigan resorts since the 19th century. The Golfmore stood three stories tall, with broad verandas and gabled roofs, all oriented to capture views of Lake Michigan’s blue horizon. Inside were 175 guest rooms, each outfitted in comfort (the hotel touted “every room with bath” on the American Plan, a big luxury at the time).

There were elegant public spaces: a spacious lobby, a fine dining room, and a ballroom where an orchestra played on summer evenings. For cooling in the summer, the ballroom relied on natural breezes off the lake through large open windows. The hotel’s name – “Golfmore” – highlighted the resort’s golfing attraction, and indeed the course was expanded to 27 holes when the hotel opened, with part of the course wrapping around the hotel grounds.

Promotional brochures for Hotel Golfmore exuded Jazz Age enthusiasm. “Let’s go for a swim,” one brochure beckoned, emphasizing the direct beach access. “When you first glimpse the three-mile stretch of fine, broad white sand beach that borders Hotel Golfmore, you will understand why it was named Grand Beach,” it promised. Another line boasted the location was “just sixty-two miles from Chicago” on a good highway – close enough for an easy trip, but far from the stress of city life.

The hotel marketed itself as a year-round resort destination, not just a summer retreat. To entice winter business, the management added unique cold-weather amenities, most famously a ski jump constructed on a tall dune near the hotel around 1923. In snowy winters, daring skiers could schuss down the wooden ramp and sail through the air, while spectators watched these thrilling ski jumping meets (complete with hot cocoa by bonfires). This was quite extraordinary – ski jumping in southwest Michigan! – and it attracted notable athletes. In January 1926, Olympic skier Anders Haugen headlined a competition at Grand Beach, soaring off the Hotel Golfmore’s ski jump to the amazement of gathered crowds.

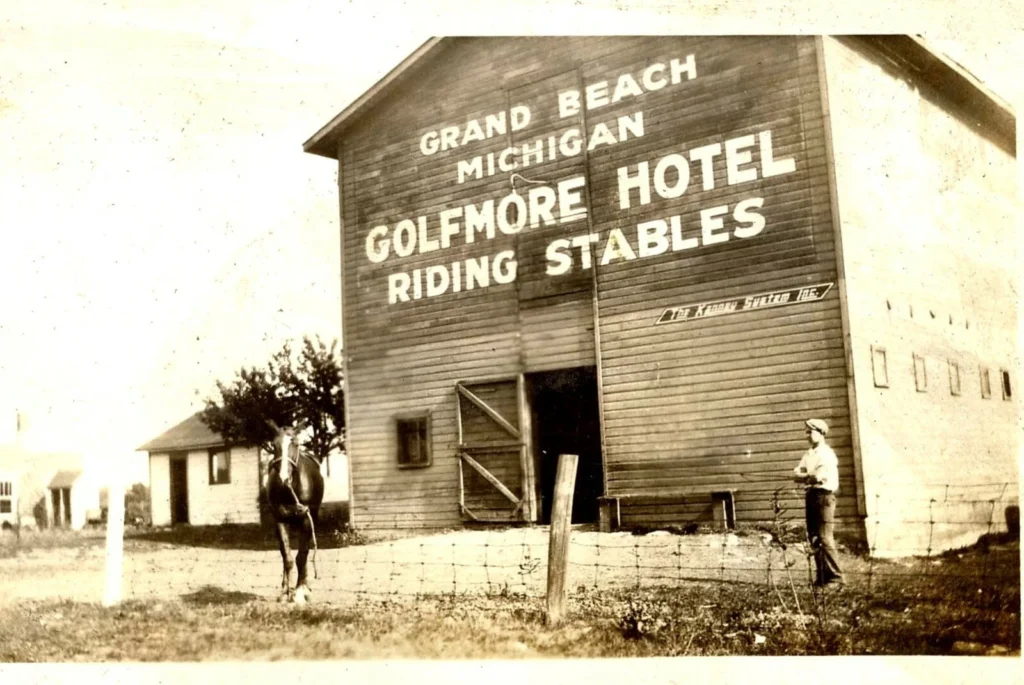

During the Roaring Twenties, Hotel Golfmore became the social heart of Grand Beach. It hosted gala dances, banquets, and holiday celebrations. Chicago society and more middle-class tourists mingled on its sweeping lakefront porch. The hotel’s facilities included tennis courts, horseback riding trails, and of course immediate access to the golf course and beach. Guests could spend the day golfing or swimming, then dress in evening attire for dinner in the hotel’s restaurant, followed by dancing. A live orchestra often played jazz and waltzes in the ballroom as couples danced under decorative lights – a scene straight from The Great Gatsby era.

The Hotel Golfmore was such a landmark that it even gained attention in sports circles: in the 1930s, famous heavyweight boxer James J. Braddock (the “Cinderella Man”) used the Hotel Golfmore as a training camp. He and his manager, Joe Gould, along with sparring partners, stayed in a cottage on the hotel grounds and trained on-site while enjoying the fresh air. Photographs from that time show Braddock and his crew jogging on the dunes and boxing in improvised rings at Grand Beach, adding a layer of legend to the hotel’s history.

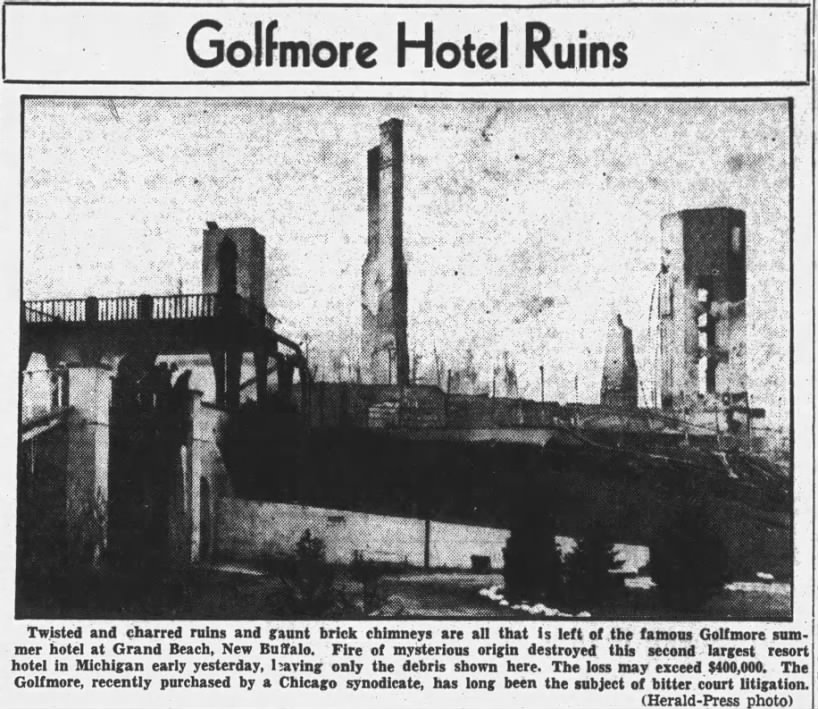

(The magnificent Hotel Golfmore met an unfortunate end – it was utterly destroyed by a catastrophic fire on November 19, 1939, bringing its 17-year run to an end. The hotel’s loss marked the end of Grand Beach’s resort era, after which the area evolved more into a quiet residential enclave. But during 1921–1930, the Golfmore reigned as the jewel of Grand Beach.

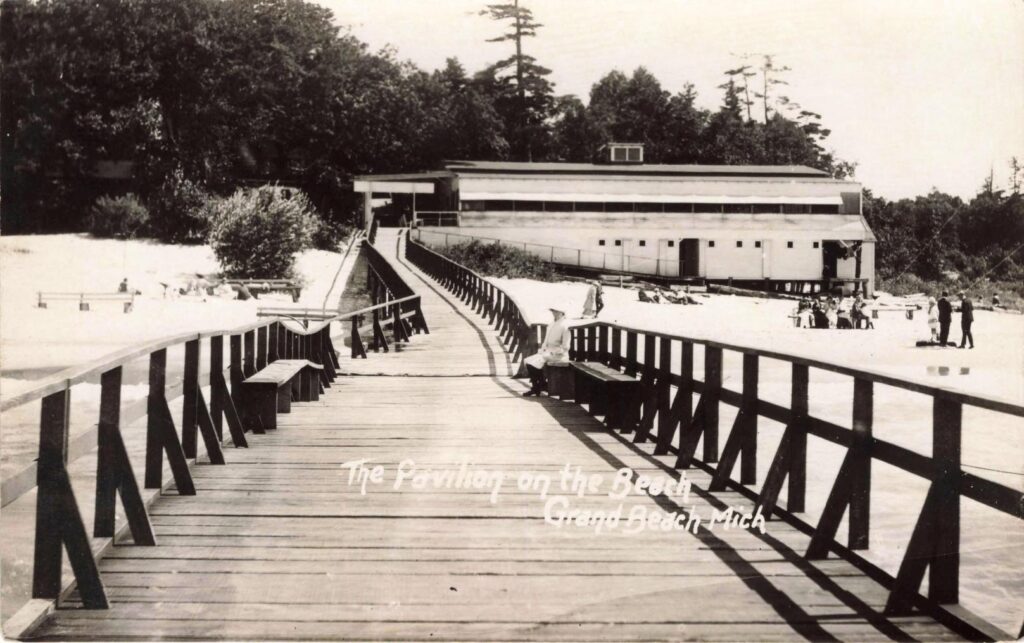

The Beach Pavilion, Dance Hall, and Leisure Culture

Daytimes at the beach pavilion were equally lively. It served as a beach house where visitors could rent bathing suits or changing rooms (in an era when many people didn’t travel wearing their swimwear). Families would spread out blankets on the sand in front of the pavilion. The lake offered excellent bathing (swimming) – Lake Michigan’s shallow sandy-bottom areas warmed up nicely in summer, and the resort maintained lifeguards for safety.

A popular postcard from the 1910s, captioned “Come on in, the water is fine!” captured the appeal of a refreshing dip on a hot day. Nearby, a wooden slide might be set up on the beach for children to play, and canoes, rowboats, and small sailboats could be rented at the boat landing for those who wanted to venture onto the water.

Fishing was another leisurely pursuit – kids might fish for minnows and perch along the creek or off the pier (hence postcards joking about “catching minnies” i.e. little fish). The creek (State Creek) that ran into the lake by the pavilion was spanned by a quaint, rustic bridge, immortalized on postcards, where couples would take evening strolls. The whole atmosphere was one of carefree recreation and scenic beauty.

One of Grand Beach’s most beloved attractions was its beach pavilion and dance hall, which embodied the spirit of summertime leisure. In the resort’s early years, a simple open-air pavilion was built near the shoreline as a gathering spot. Then, around 1919–1920, the Grand Beach Company enhanced this into an “entertainment pier” that extended out over Lake Michigan. At the end of the pier sat a large pavilion structure – essentially an over-water dance hall with a broad hardwood dance floor and a roof to shelter from the elements. On warm evenings, this pavilion would glow with lights as live bands played foxtrots, two-steps, and waltzes popular in the Jazz Age.

Tourists staying in Grand Beach or neighboring towns would flock to the pavilion for dancing under the stars, cooled by the lake breeze. One account recalls “the strumming notes of a guitar and banjo, the moon rising above the treetops…” creating an enchanting nightlife scene on the pier.

Couples in summer flapper fashions could be seen swirling across the floor. In contrast, others sat at tables along the edges, enjoying refreshments and the panoramic view of the lake in moonlight. Dining was also offered – the pier had a café where one could eat fresh local Whitefish or sip iced drinks while watching the sunset. The posts of this pier remained visible decades later during low water, a testament to its robust construction.

Daily life and recreation in the 1920s at Grand Beach revolved around these simple pleasures. A typical summer day for a visitor might start with a morning round of golf on the expanded course, followed by a hearty lunch at the dining hall or on the hotel’s veranda. In the afternoon, families headed to the beach – children building sandcastles or splashing in the lake, while adults relaxed under parasols.

Some would go horseback riding on bridle trails that wound through the dunes (the resort maintained a small stable for trail riding). Others hiked or toured the area’s natural sights – the woods and shifting dunes provided an “ever-shifting, entrancing panoramic view” for those exploring the trails. By late afternoon, many gathered at the boat landing to watch the sunset colors on the water or to try a short excursion on a motor launch.

When the sun went down, Grand Beach did not sleep. Evenings were for community and entertainment. Often the festivities centered on the dance pavilion: residents of all ages would put on their best summer outfits and head to the pier. Live music (perhaps a local jazz ensemble or a pianist with a Victrola) struck up tunes that drew dancers to the floor every night except Sundays.

The pavilion’s fame spread – it was said, “Twilights spent on the broad terrace at Golfmore [the hotel] or dancing on the shimmering floor of the pavilion are not soon forgotten.” On weekends, the crowds swelled, sometimes joined by visitors from Chicago who came out just for the Saturday night dance via the last afternoon train.

Beyond dancing, there were bonfire parties on the beach, moonlight picnics, and occasional fireworks for holidays like the Fourth of July. The casino provided a quieter diversion where gentlemen (and some ladies) might play cards or roulette for low stakes. And for those simply seeking relaxation, the lodge and lounge facilities (including the hotel’s plush lounge) offered space to read, converse, or play board games. Grand Beach in the 1920s thus cultivated a wholesome yet vibrant recreational culture – it was a place where youthful fun and genteel leisure coincided. Teenagers could flirt at the dance hall, children could chase fireflies, and parents could socialize on a porch rocking chair, all amid the sound of crickets and lapping waves.

Notable People, Events, in the History of Grand Beach

Despite its relatively remote location, Grand Beach attracted its share of notable figures and memorable events during its golden era. As mentioned, Frank Lloyd Wright – America’s most famous architect – designed three cottages here around 1916, indicating that prominent Chicago families were among the early lot owners. (One of these, the Ernest Vosburgh summer house, still stands as a local architectural treasure.) The presence of Wright-designed homes hints at an upscale element in the community’s social fabric. Grand Beach hosted golf tournaments and exhibition matches on its course, drawing skilled golfers from the region. The ski jumping tournaments in winter brought in Olympic-level athletes like Anders Haugen, putting Grand Beach briefly in national newspapers as an unlikely Midwestern skiing venue.

Training For World Heavyweight Champ James Braddock

In the realm of popular culture, James J. Braddock’s training camp at Hotel Golfmore in the mid-1930s became part of boxing lore. Braddock arrived as a down-and-out fighter to train on the peaceful dunes, and he left in peak condition – going on to win the heavyweight championship in 1935 as the “Cinderella Man.” The fact that Braddock and his entourage trained at Grand Beach (sparring in the hotel’s facilities and running on the beach) gave the resort a brush with sports history.

Local memory holds that other Chicago celebrities of the era, including politicians and businessmen, would visit Grand Beach for quiet retreats. It wasn’t unusual to see a Packard or Cadillac with Chicago plates parked under the trees by a cottage, the owners enjoying anonymity and relaxation away from the city.

Societally, Grand Beach reflected broader patterns of the 1910s–1920s: the rise of a middle class with leisure time, improvements in transportation, and the nation’s embrace of outdoor recreation. It stood alongside other Lake Michigan resort communities (like Union Pier, Ottawa Beach, and Long Beach) as part of the “Chicagoans’ Riviera” – a string of beaches and summer colonies where city folks built second homes or visited resorts to escape urban heat.

Grand Beach’s particular mix of amenities (golf, bathing, dancing, gambling) was a microcosm of Jazz Age recreation, albeit in a family-friendly package. Men might wear their new straw boaters, and women might wear their flapper dresses, at a dance. Yet, Prohibition-era rules were politely bent as illegal cocktails possibly flowed discreetly at private cottage parties or the hotel (there were rumors of a speakeasy corner in the Golfmore’s bar during the 1920s). By day, however, the atmosphere remained wholesome and rejuvenating, promoting healthful activities in the fresh air.

Legacy of Grand Beach’s Golden Era

Grand Beach’s legacy from 1890 to 1939 is that of a thriving resort village that successfully leveraged its natural beauty and strategic location. It transformed from wild dunes into a landscaped getaway that still retained a rustic charm.

The period of the late 1920s was arguably its zenith – a time when special excursion trains, packed with passengers in summer whites, would arrive at the “Grand Central” depot; when the dance hall floor shook with the Charleston; and when Lake Michigan’s horizon was dotted with sailboats and the smoke of steamers. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 slowed development and thinned the crowds, as fewer families could afford vacations. Many cottages went unused for the summer or were sold.

Today, the village still cherishes that history – the original golf course (now nine holes) remains a centerpiece of the town, the old gates still stand white and proud, and historical markers and photos celebrate the era of excursion trains, pavilion dances, and the grand Hotel Golfmore. The story of 1890–1939 in Grand Beach is a vivid chapter of American leisure history – a time when an escape to “the grand beach” of Michigan meant sunshine, sport, and a taste of the good life by the lake.

Sources for the History of Grand Beach

Historical postcards and photographs from the David V. Tinder Collection (University of Michigan) were used to illustrate period scenes.

Key factual details were drawn from the Village of Grand Beach official history, the New Buffalo Township historical profile, and contemporary accounts such as The Beacher newspaper’s 2017 feature on Hotel Golfmore and Grand Beach’s early years.

Additional context on transportation and social life was gathered from regional histories and the Encyclopedia of Chicago. These sources collectively ensure an accurate timeline and portrayal of Grand Beach during its resort heyday.