The history of De Tour, Michigan, begins long before it was a village on any map. The earliest residents of De Tour were the Mascoutin, Ottawa, and Chippewa Native American peoples, who established encampments at Pointe De Tour well before European travelers arrived. This strategic spot at the mouth of the St. Marys River was known to Indigenous communities for generations.

French explorers passed through in the 17th century (names like Father Marquette and La Salle appear in regional lore), and France claimed the area until Britain took over in 1761. The name “De Tour” is French for “the turn,” a fitting description of the sharp turn ships make to navigate from Lake Huron toward Lake Michigan and the Straits of Mackinac. French voyageurs reportedly called this site “the turning point” on their canoe routes to Mackinac Island. Long before Detroit or Chicago existed, De Tour’s harbor was a stop for traders and a place to take on firewood, making it an important if little-known landmark on the Great Lakes.

Video – Edge of the Great Lakes: The Untold History of De Tour, Michigan

Early History of De Tour Michigan

American settlement in the area began in the mid-19th century. In 1850, during Michigan’s territorial years, the U.S. organized the locale as Warren Township, named after Ebenezer Warren, its first postmaster. An 1848 map even labeled the tiny settlement “Warrenville.” A few years later, in 1856, the postmaster Henry Williams officially changed the name to “De Tour” (sometimes spelled as two words) to reflect the long-used French term. During these years, De Tour was a sparsely populated hamlet, but its location was already key.

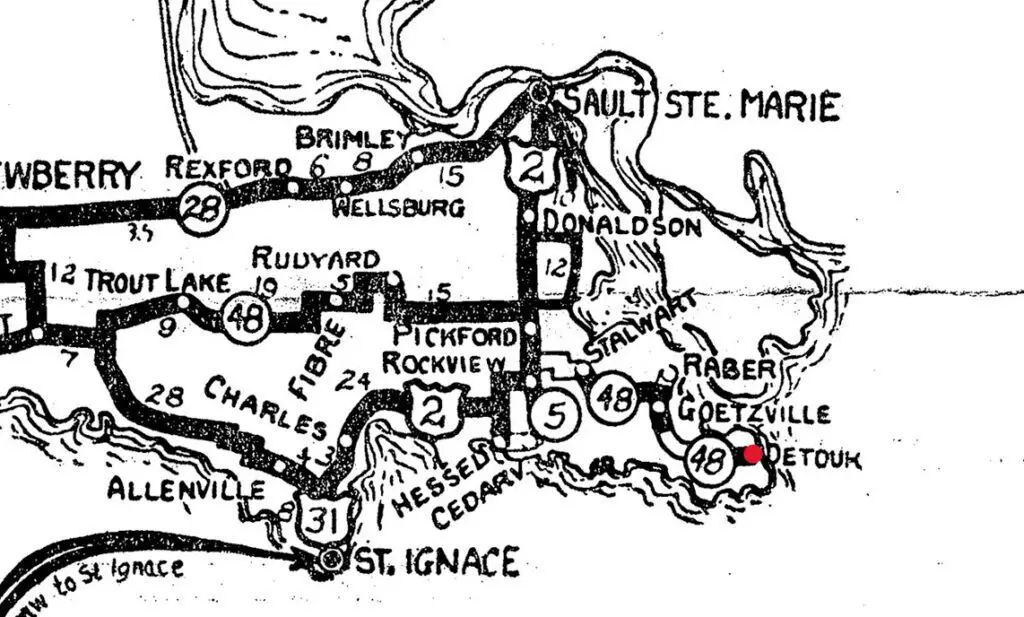

The Point De Tour Light was established in 1847 onshore to guide ships through the dangerous turn in the St. Marys River channel. When the Soo Locks opened upstream at Sault Ste. Marie in 1855, it unleashed a flood of steamboats and schooners onto Lake Huron. Nearly all traffic to and from Lake Superior had to “detour” past this point. Suddenly, De Tour found itself at the crossroads of a burgeoning maritime highway.

Lumber Boom and Village Incorporation

In the late 1800s, the lumber industry swept into Michigan’s eastern Upper Peninsula, and the history of De Tour, Michigan, entered a boom period. Stands of old-growth pine and cedar in the region attracted timber barons and sawmill operations. By the 1880s and 1890s, lumber camps and mills sprang up around De Tour. Huge rafts of logs were floated to local sawmills or loaded onto steam barges.

One large sawmill, built around 1890 by entrepreneurs from downstate, became the economic engine of the village. During these boom years, De Tour’s once-tiny population swelled. The 1900 U.S. Census recorded 880 residents in De Tour– a remarkable number for a remote village. This growth prompted community leaders to seek official status. In March of 1899, township officials petitioned to incorporate the village. That year, De Tour was chartered as DeTour Village, formalizing its identity on the map (the spelling would later be stylized with a capital “T” in 1953).

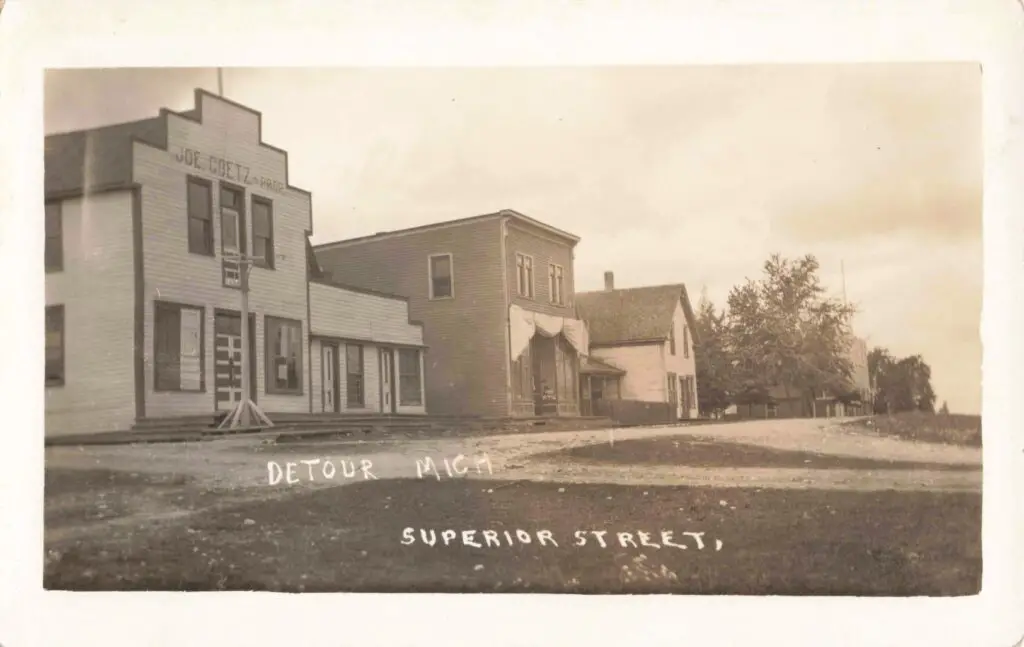

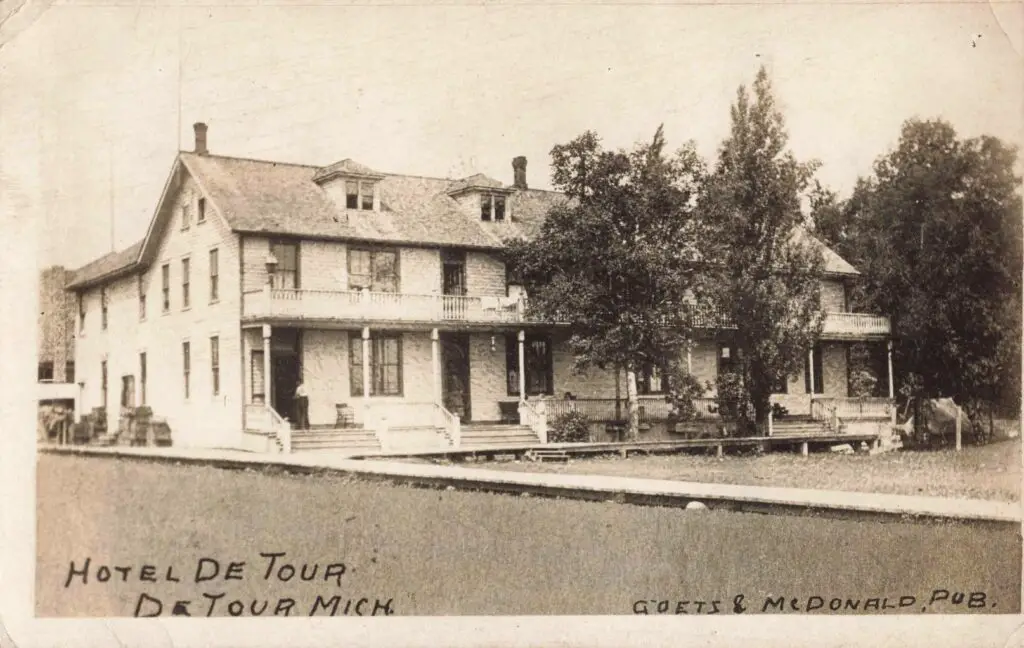

By 1900, De Tour Village was buzzing with activity. Superior Street, the sandy main road along the waterfront, bustled with shops and boarding houses. A general store supplied everything from beans to boots. A modest white hotel welcomed lumber crews, sailors, and the occasional land speculator off the steamships.

The post office, a simple wooden building often seen in old photos, served as the communications hub – the place where residents picked up mail, caught up on news, and maybe traded a few fish stories. The village’s harbor, opening onto De Tour Passage, saw constant traffic. Freight steamers, packet boats, and even commercial fishing tugs came and went. De Tour became an official Great Lakes port of call, a coaling and supply stop between the Straits of Mackinac and Sault Ste. Marie.

Life at a Great Lakes Crossroads

Around the turn of the 20th century, daily life in De Tour mixed hard work with simple pleasures. Many families in the village had ties to the lumber trade – fathers or sons might work at the sawmill or in winter logging camps inland. Others made a living on the water, fishing or working as deckhands on steamers. School classes were small, and children helped with chores like stacking firewood or picking berries in the summer. Still, there was time for leisure. Residents held church socials and dances at the hotel. On Saturdays, farmers from nearby areas rode into town by wagon to trade goods and hear the latest gossip outside the general store on Superior Street.

Because of its unique position on the shipping lane, De Tour offered front-row seats to a maritime parade. Enormous ore freighters laden with iron from Minnesota regularly passed just offshore. Locals learned the freighters’ names and whistles – an approaching steamship’s deep horn echoed across the water, signaling news from the outside world.

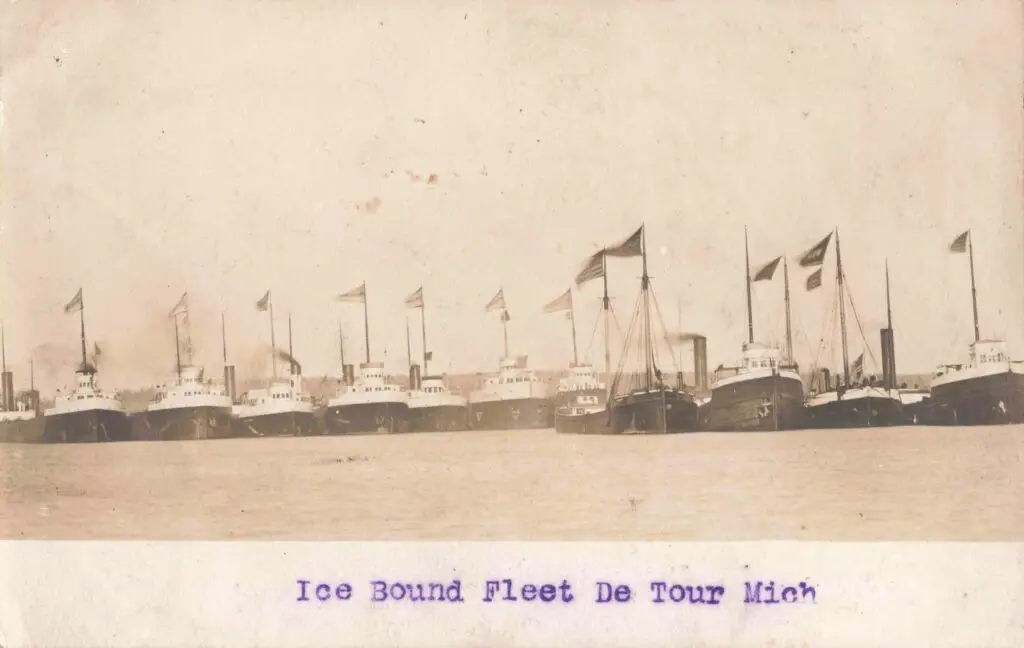

When the mail boat arrived from the Soo, villagers gathered at the dock as sacks of letters and parcels were unloaded, bringing distant places a little closer. Seasonal drama came each year with the ice. In late fall, the last downbound freighters raced to beat the freeze.

Some winters, the freeze-up came early and hard. Photographs from the 1910s show a dozen freighters trapped in ice near De Tour’s harbor – a literal “ice-bound fleet” waiting for spring to thaw them out. During those times, the village turned quiet, essentially cut off until navigation resumed. Such scenes became part of the lore and history of De Tour, Michigan, captured in faded postcards and memories.

Despite the challenges of isolation and hard work, community spirit thrived. Neighbors supported each other through rough weather and economic ups and downs. The village school, churches, and civic groups like the Ladies Aid Society provided social life and charity. De Tour may have been far from Michigan’s urban centers, but to its residents, it was the center of a richly textured world – one defined by the rhythm of seasons and ships.

Cottages and a Touch of Tourism

Even as the lumber era peaked and began to wane, another chapter in De Tour’s story emerged: summer tourism. The same natural beauty and “up north” remoteness that posed challenges for year-round residents proved appealing to outsiders seeking recreation. By the 1910s, local entrepreneurs opened small resorts around De Tour, especially along the idyllic shores of Caribou Lake, a few miles inland.

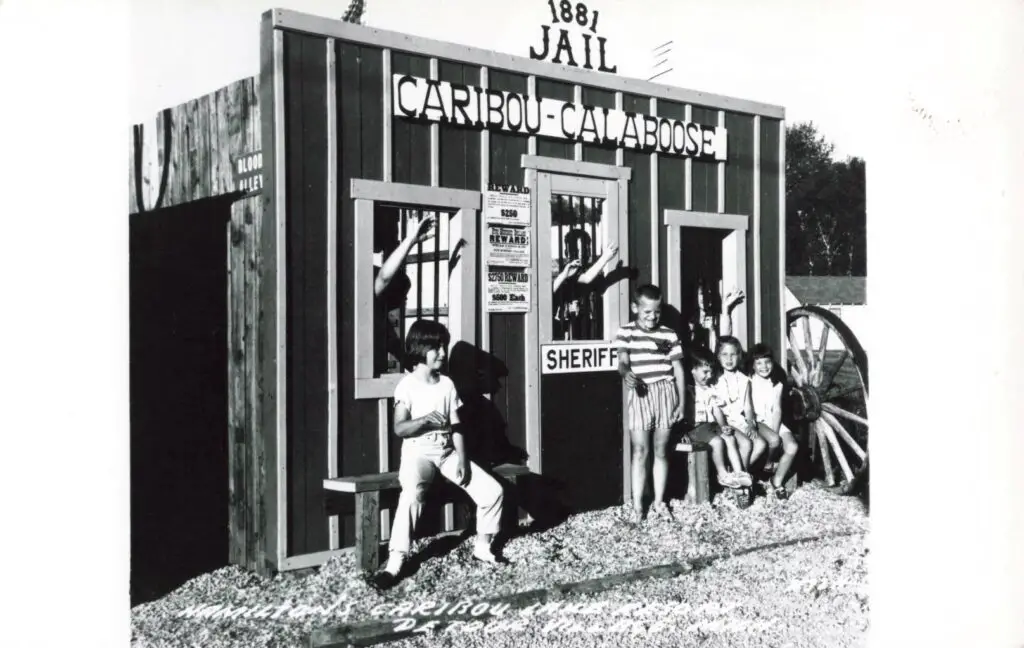

One of the most popular spots was Hamilton’s Caribou Lake Resort, which drew guests for fishing, boating, and relaxation. To entertain visitors, the resort’s owner, Kent Hamilton, built a miniature steam locomotive that ran on a narrow-gauge track around the property. Guests could ride this “Caribou Lake Railroad” through the pine woods, a delightful novelty that left a lasting impression on those who experienced it.

Another nearby establishment, Ingersoll’s Cottages, offered rustic log cabins where city dwellers from Detroit or Chicago could spend a week in the wilderness. They fished for pike and perch by day and gathered around bonfires by night. The arrival of these tourists each summer brought a little extra income and a cosmopolitan air to De Tour. Local teens might find summer jobs guiding fishing trips or helping in the resort kitchens.

The sight of an automobile or two (after the 1920s) with out-of-state license plates became more common on Superior Street as adventurous motorists discovered the Upper Peninsula. Though tourism never overtook lumber or shipping in De Tour’s economy, it became part of the village’s character. Outsiders were discovering what locals already knew – that this remote corner of Michigan held a special charm.

After the Boom: Mid-Century and Preservation

By the 1920s and 1930s, the great pine forests around De Tour were largely depleted, and the lumber boom faded. The big sawmill closed, and many lumbermen moved on to other frontiers. The village’s population, which had been 721 in 1910, declined to about 600 by 1940. Young people left to find work in larger towns or to serve in World War II, while some families stayed on, continuing traditions of fishing, small-scale logging, or working on the freighters.

In 1931, the DeTour Reef Light was constructed on a concrete crib out in the channel, replacing the old Point De Tour lighthouse. Its powerful beacon and foghorn guarded the passage, underscoring the fact that maritime activity remained vital. Freighters still passed daily (carrying iron ore, grain, and limestone), and Drummond Island, just across the channel, relied on De Tour’s ferry service as its link to the mainland.

In 1950, the Census counted 611 residents in DeTour Village. The community was smaller and quieter than in its heyday, but it endured. In 1953, the spelling of the village’s name was formally changed from “Detour” to “DeTour” – capital T – to reflect its French origin. And in 1961, the post office was officially renamed “DeTour Village”, cementing the usage locals had long embraced.

As the decades went on, preserving the history of De Tour, Michigan became a community priority. Retired lighthouse keepers, fishermen, and teachers shared stories of the old days with younger generations. In the 1980s, a group of volunteers founded the DeTour Passage Historical Museum in the former town hall building. Today, the museum displays artifacts like the original 3½-order Fresnel lens from the 1931 lighthouse, photographs of ice-locked ships, a scale model of the Caribou Lake Railroad, and genealogy records of founding families.

Although De Tour never again saw the bustle of 1900, the village entered the 21st century with pride in its heritage. Its location is still crucial – freighters ply the same route (nearly 5,000 vessel passages each year) and boat-watchers line the shore to wave at the crews. Tourists still arrive each summer, drawn by world-class fishing and the quiet beauty that the first campers and voyageurs marveled at. The History of De Tour Michigan is one of resilience and adaptation: from native encampments to a lumber boomtown, from a shipping crossroads to a close-knit small village. Through all these changes, De Tour has retained its identity as the little harbor at “the turn” – a place where the broader currents of Great Lakes history swirl around a proud, enduring community.