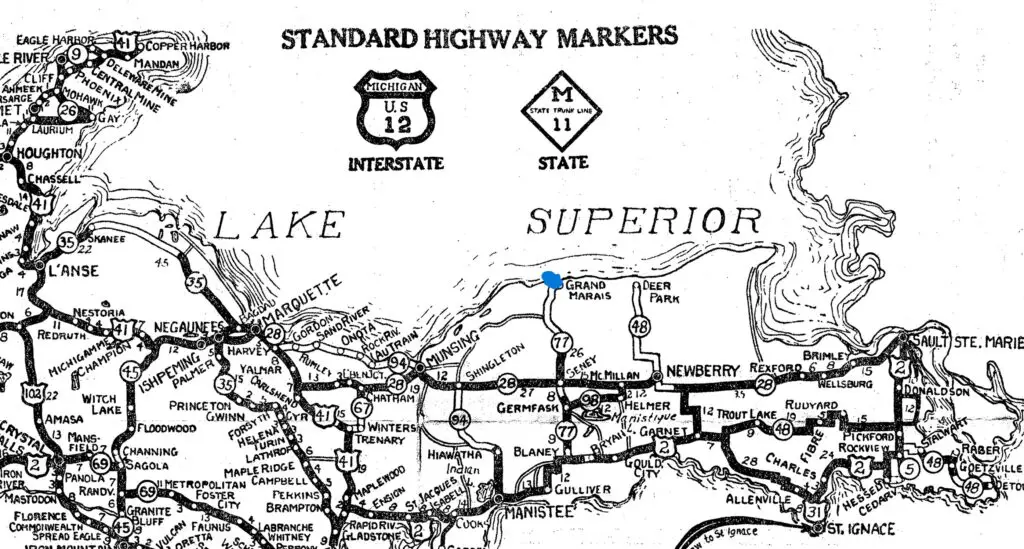

As a kid, we travelled and explored Grand Marais. It is quite literally at the end of the road on M-77. There is plenty to do; explore the nearby Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, including Sable Falls and the Log Slide Overlook. Visit the Au Sable Light Station, Pickle Barrel House, or the Gitche Gumee Museum. Or better yet, take a camera and seek the scenic beauty of Lake Superior, relax on beaches, or hike and bike the trails. I wanted to learn more about Grand Marais’ history and how it became such an excellent getaway on the shore of Lake Superior.

Table of Contents

Video – Grand Marais: Lumber, Fish, and a Legacy

Grand Marais History of Indigenous Culture and Early Settlement

Long before Grand Marais appeared on any map, Ojibwe (Chippewa) bands fished and camped along this Lake Superior shore. French voyageurs applied the name Grand Marais (“Great Marsh”) to its broad harbor (in French, the word marais could mean a sheltered bay as well as a marsh). In the mid-1800s, the harbor drew a fur-trade outpost and seasonal fishing camps. By the 1860s, Euro-American settlers began to arrive, drawn by the rich timber and fish resources. The town itself was officially platted in 1883 by lumber baron Wellington R. Burt, who envisioned a bustling mill town.

The Lumber Boom (1880s–1909)

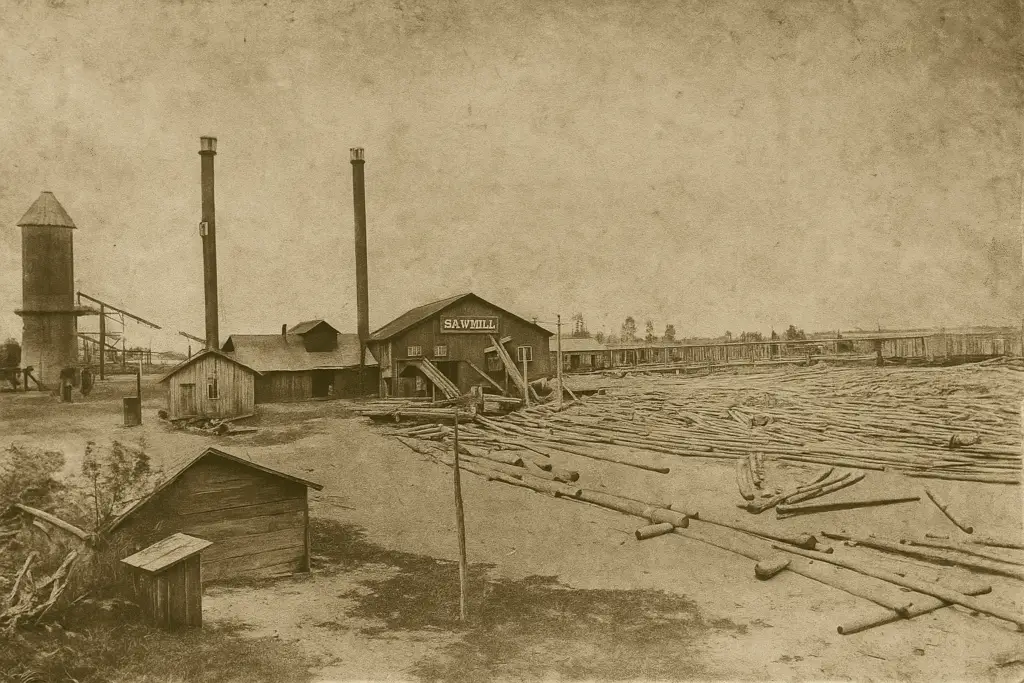

In the late 19th century Grand Marais was built on logging. Geologists and speculators had found vast stands of white pine here. From about 1880 on, lumber companies put hundreds of men to work cutting timber in the surrounding forests. Small logging camps fed temporary rail spurs and sleigh roads. For example, Prentiss & Eastman (a major Michigan lumber firm) sent 300 men and teams under manager Thomas G. Sullivan, who felled some 50 million board feet of pine by 1885.

Grand Marais mills turned these timbers into shingles, beams and squared logs. By 1897 sawmills were fed by 40 miles of temporary logging railroad, shunting logs to the shore. In the mid-1890s a railroad spur (the Manistique Railroad) was extended 25 miles north from Seney, allowing rapid shipment of lumber and bringing a boom: by 1896 one mill was shipping 40 million board-feet per year and the town’s population swelled to roughly 2,000. The image above illustrates the era: loggers stand on a floating raft of pine logs in Grand Marais harbor (circa 1900).

Despite this boom, the pine was finite. By 1909 the Marais Lumber Company (then the last major firm) ran out of timber and closed its mill. When the railroad removed its tracks in 1910, the boom town rapidly shrank: official counts fell from 300 people in 1884 to only 177 by 1890, and settled at a few hundred thereafter. In essence, the era of large-scale lumbering ended by the 1910s, leaving Grand Marais much smaller and more isolated.

Harbor and Transport Infrastructure

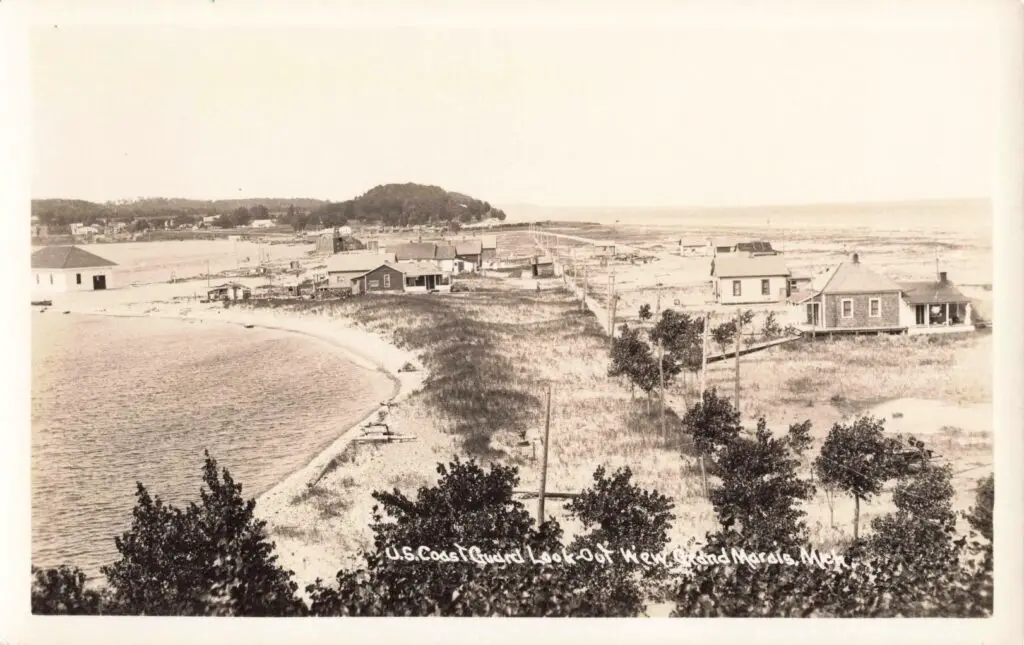

Throughout the lumber era, Grand Marais also built marine infrastructure. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged and extended the harbor, adding piers and a breakwater. By the early 20th century, a stone breakwater and range lights guarded the entrance (the Grand Marais Outer Range Light, built 1882, still has its original Fresnel lens)

In 1899, the U.S. Life-Saving Service (a precursor to the Coast Guard) opened Station Grand Marais at the harbor, providing rescue services for shipping. Inland, Wellington Burt’s firm and its successors also platted town streets and sold lots; in 1893, Burt sold the entire townsite to mill interests. During the boom, a narrow-gauge railroad (“Manistique Railroad”) hauled logs and goods north. After 1910, this rail link was abandoned, but in the 1930s, the state finally built a highway (now H‑58/M‑77) into town, restoring year-round road access.

Commercial Fishing and Maritime Trade

A critical pivot point with Grand Maris history was when the lumber mills left, fishing became a core industry. Grand Marais sits on rich Lake Superior waters, and by the 1870s the first commercial fishermen had arrived (one early pioneer was Emil Endress around 1871). Boats and tugs plied the bay for lake trout, whitefish and other species. The community became a fish processing and transshipment point: catches were iced or packed in salt and shipped by rail and steamer to markets in Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee and beyond. (Between 1900–1910 the U.S. Fish Commission even stocked the lakes with 25 million whitefish and 8 million trout fingerlings to support the fishery.) Record hauls were reported; for example, in 1904 one Grand Marais crew landed 12,000 pounds of trout on a single outing.

Ethnic immigrant communities dominated the fishing fleet. Finnish families (like the Niemis) and German-Americans (like Emil Endress’ clan) were prominent. The Niemi family in particular built their own boats: Otto Niemi’s hand-built tugs Elk (1923) and Shark (1940) ran from Grand Marais for decades. Other Scandinavian and Eastern European fishermen also worked the waters. In this way, Euro-American settlers simply replaced the earlier Ojibwe fishing labor, and Grand Marais thrived as a year-round fishing harbor into the 1940s.

The economic impact was significant: by the mid-20th century, Grand Marais and Sault Ste. Marie was noted as an excellent transshipment point for Great Lakes fish to industrial markets. Seasonal rhythms persisted (spring and fall were peak harvest times), but by the 1950,s the arrival of sea lampreys decimated lake trout stocks. A Grand Marais fisherman noted that by the 1950,s “the lamprey was taking its toll on Lake Superior’s trout”, signaling a steep decline in the once-booming fishery.

Tourism and Recreation

As extractive industries faded, tourism gradually emerged. Even before 1920, Grand Marais’ scenic harbor and wilderness attracted some campers and travelers to nearby Pictured Rocks. After 1910, the town invested in recreation: the lumber company donated prime land that became Woodland Park, a public campground opened on the lakeshore. In the 1930s, the new highway (State Route 77, now County H-58) finally linked Grand Marais to the rest of Michigan by road. This brought a modest influx of auto tourists and anglers.

By the 1940s and ’50s, camping, hunting, hiking, and charter fishing trips were common summer activities. For example, one outdoor writer recalls that in the early 1950s, “trout fishing in Lake Superior was one of the main attractions and dozens of charter captains fished for lakers” out of Grand Marais.

The town’s dual piers and sandy beach made it a popular regional getaway. In short, Grand Marais evolved into a four-season outdoor destination: summer campers and fishermen, as well as winter sports enthusiasts (ice fishing, snowmobiling), gradually filled local lodging, stores, and restaurants. By 1960, tourism had not yet reached the levels of later decades, but it was clearly the town’s leading hope for the future.

Economic Trends and Challenges

Overall, Grand Marais’ economy saw boom-and-bust cycles. The late-19th-century logging boom brought rapid growth; its 1910 bust left only a few hundred people behind. After 1910, the village settled into a “small but stable” community supported by fishing and whatever logging remained. Isolation was a perennial challenge: locals recall that winter access could require dogsled or skis over 25 miles of snow after the railroad left to reach the nearest town of Seney.

During the Great Depression and wartime era, residents relied on subsistence gardening, hunting, and fishing; a 1946 diary notes how rationing made even basic foods very hard to get. The 1930s road finally eased isolation, and electricity and telephone service eventually arrived, but even mid-century, Grand Marais was far from industrial centers. The community struggled to adapt when natural-resource industries declined (pines cut off, fish overharvested by lampreys). In broad terms, by 1960, Grand Marais had reverted to a quiet village of a few hundred residents, with limited industry and an economy turning toward tourism and service jobs.

Notable Figures and Communities

- Wellington R. Burt (1831–1919) – Michigan lumber baron who platted “West Grand Marais” in 1883. His company later sold the townsite to investors when logging began.

- Thomas G. Sullivan – Prentiss & Eastman lumber manager who led massive pine-cutting crews in the 1880s, felling an estimated 50 million board feet.

- Walter Bell – An early settler (from Canada in 1880) who became a storekeeper and local leader during the lumber era (originally a clerk for the Randolph Lumber Co.). [Local histories note his pioneering role, though few primary documents survive.]

- Carl Emil Endress – German-American fisherman credited as the first Euro-American commercial fisherman in Grand Marais (c. 1870s). His family’s partnership shipped iced fish to Chicago and the Upper Midwest.

- Otto Niemi (1881–1970) – Finnish-born master fisherman who built and operated a fleet of hand-crafted fish tugs from Grand Marais for nearly five decades. (The town’s Gitche Gumee Agate Museum preserves his story.) His family retired the last tug in 1953 when lampreys wrecked the fishery.

- Dennis Weaver (1924–2006) – Though arriving later, Weaver (Hollywood actor and conservationist) settled here in the 1980s and helped revive Grand Marais as an outdoor tourist destination. He later recalled in interviews that “Grand Marais has come back” thanks in part to renewed interest in Lake Superior recreation.

- Ojibwe (Chippewa) communities – The Anishinaabe people, native to this region, were the first stewards of the Grand Marais area. They fished these waters and traded at this bay for generations, providing the earliest “industry” long before 19th-century lumber or fish crews. (Treaty rights and cultural ties to these lands remain part of the community’s heritage.)

Each of these individuals and people helped shape Grand Marais. From Ojibwe fishing camps and French voyageurs to lumber magnates, Finnish fish tugs, and later outdoor enthusiasts, the town’s story is one of adaptation to changing times. Primary sources – from National Park Service records and Coast Guard archives to local court filings – document these changes in detail. (For example, Michigan appellate records explicitly note Burt’s 1883 platting of the town, and NPS histories chronicle the logging-driven boom and decline.) This deep historical record can guide modern storytelling: a Ken Burns–style narrative can weave these economic and personal threads into a vivid portrait of a remote village’s rise, fall, and rebirth on the shores of Lake Superior.

Acknowlegements

Government and archival histories (e.g., National Park Service logging archives, Coast Guard station histories, Michigan Court records) as well as contemporary accounts from local historians provide the basis for this review. In particular, materials from the Gitche Gumee Agate & History Museum and published historical essays on Grand Marais have been invaluable for local color and detail. Each quoted fact above is cited to a line from these sources

Sources Cited:

- National Park Service. “Logging History.” Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, www.nps.gov/piro/learn/historyculture/logging.htm.

- “Gitche Gumee Agate and History Museum.” Gitche Gumee Museum, www.agatelady.com.

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “Commercial Fishing History.” Michigan.gov, www.michigan.gov/dnr/managing-resources/fisheries/commercial-fishing.

- Alger County Historical Society. “Grand Marais History.” Alger County Historical Society, www.algercountyhistoricalsociety.org/grand-marais.

- Coast Guard History. “U.S. Coast Guard Station Grand Marais.” U.S. Coast Guard, www.history.uscg.mil/Stations/Grand-Marais.