In the fall of 1815, a young fur trader named Louis Campau made his way up the Saginaw River. His journey and the establishment of the Campau Trading Post would change the course of Michigan’s history.

Just 25 years old, Campau had been sent north from Detroit by his uncle, Joseph Campau, one of the wealthiest men in the Michigan Territory. His mission was simple: establish a permanent trading post deep in the woods of the Saginaw Valley and open up trade with the Anishinaabe, the region’s longtime residents.

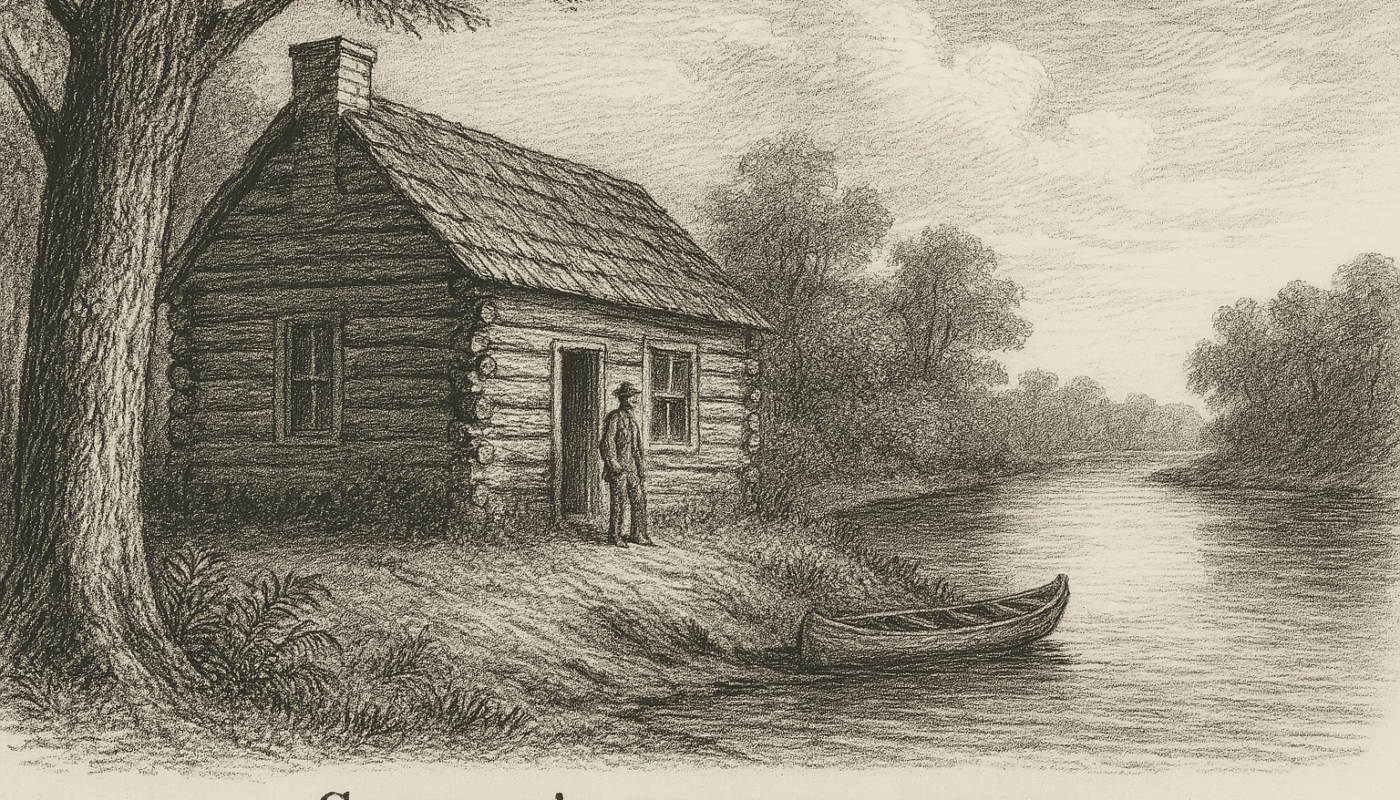

Campau chose a high bluff on the west bank of the river. There, he built a two-story log structure of squared timbers—a building sturdy enough to be a fortress, if needed. This post would become the first permanent white settlement in what is now Saginaw, Michigan.

For the next several years, Campau traded with the local Ojibwe (also called Chippewa) communities. The fur trade dominated the region’s economy, and Campau’s Trading House quickly became a hub. Native trappers brought in beaver, muskrat, otter, and fox pelts, which Campau purchased in exchange for goods like cloth, knives, kettles, tobacco, and liquor. Campau was said to treat the Ojibwe fairly, and he earned their trust as a result.

The trading house wasn’t just a place of commerce—it became a meeting ground between cultures. Campau’s younger brother Antoine, nicknamed “Wabos” or Rabbit, helped run the post. The Campaus were among the few Euro-American residents in the area, and their relationships with Indigenous leaders were critical to the post’s success.

By 1819, Campau’s Trading House was more than a business—it had become a political landmark.

The 1819 Treaty of Saginaw

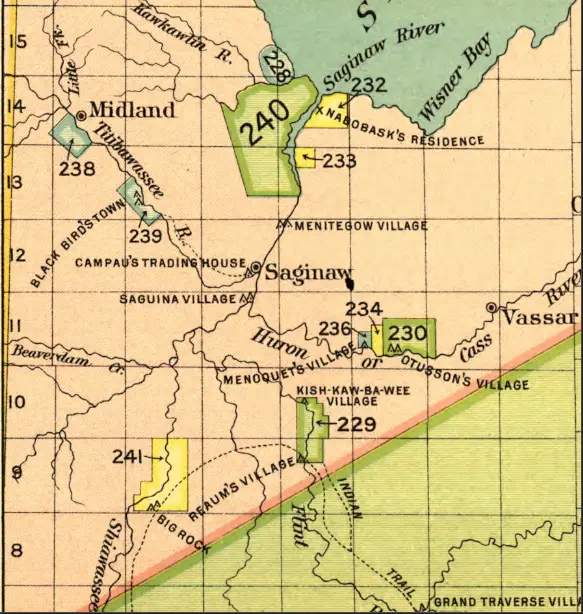

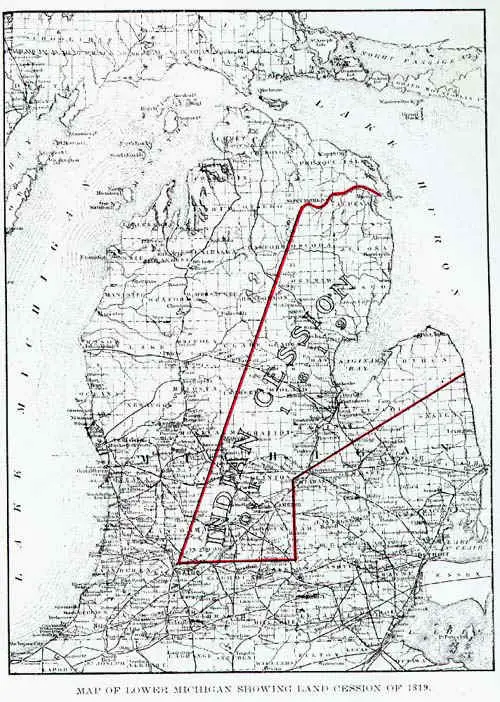

In September 1819, Michigan Territorial Governor Lewis Cass arrived in Saginaw to negotiate a land treaty with the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi. The goal: to acquire more than 6 million acres of central Michigan for white settlement.

The treaty council was held at Campau’s Trading House.

Over the course of several days, hundreds of Native men, women, and children camped around the post. Leaders met with Cass and his team. Louis Campau acted as an interpreter and advisor. The location of the trading house was even used in the treaty language to define the boundary of land being ceded.

On September 24, 1819, the Treaty of Saginaw was signed. It marked the largest land cession in Michigan up to that point, including what is now Saginaw, Flint, Midland, Lansing, and surrounding areas.

In exchange, the tribes received annuity payments and small reservations. But, like many treaties of the time, the promises made were not always honored.

A City Rises from the Forest

Following the treaty, Campau remained in Saginaw for a few more years before relocating to the Grand River to found Grand Rapids. His brother Antoine took over the Saginaw post until it was sold to other traders in the 1820s.

Campau’s Trading House stood near what is now Court Street and Hamilton Street in downtown Saginaw. The U.S. Army later built Fort Saginaw on the same site in 1822, though it was abandoned a year later. Still, the site became the nucleus for a growing frontier town.

By the 1840s and 1850s, the lumber boom transformed Saginaw into one of the most important industrial cities in the state. But it all began with a log building on the riverbank and a trader who knew how to navigate between two worlds.

Alexis de Tocqueville’s Visit to Saginaw 1831

In 1831, French diplomat and historian Alexis de Tocqueville, accompanied by his friend Gustave de Beaumont, embarked on a journey through the United States to study its society and institutions. Their travels led them to Michigan, where they sought to experience the American frontier and observe Native American cultures firsthand. This expedition is detailed in Tocqueville’s account, A Fortnight in the Wilderness.

During their Michigan travels, Tocqueville and Beaumont ventured from Detroit along the Saginaw Trail, passing through Pontiac and Flint. They aimed to reach Saginaw, then considered the edge of European-American settlement. Along the way, they engaged with local inhabitants, including settlers and Native Americans, gathering insights into frontier life and the transformations occurring in the region

Upon reaching Saginaw, Tocqueville observed the small settlement’s dynamics and the interactions between its diverse inhabitants. He noted the presence of both European settlers and Native Americans, reflecting on the cultural exchanges and tensions inherent in such frontier communities. While Tocqueville documented various trading posts and settlements, specific mention of a visit to Louis Campau’s trading post in Saginaw is not evident in his writings. Campau, recognized as Saginaw’s first white settler, established his trading post in 1816, facilitating commerce between European settlers and Native American tribes.

The Legacy of Campau Trading Post

Though the building is long gone, its historical footprint remains. It’s remembered as where the Saginaw Valley’s fur trade thrived, where trust was built between settlers and tribes, and where a monumental land treaty forever changed the course of Michigan.

Through the Campau Trading Post, Louis Campau facilitated significant exchanges and fostered relationships with Indigenous peoples.

Campau’s Trading Post represents the complicated start to Michigan’s statehood story. It’s a symbol of trade, diplomacy, loss, and growth. And it reminds us that sometimes, history turns not on battles or borders—but on a handshake beside a river.

At the Campau Trading Post, Campau played a vital role in the political landscape of early Michigan.