In 1966, a nuclear reactor just 30 miles from Detroit partially melted down in what is now known as the 1966 Fermi 1 nuclear incident—and almost no one knew. The Fermi 1 fast breeder reactor near Monroe suffered a coolant failure that caused two uranium rods to overheat. The 1966 Fermi 1 nuclear incident was America’s first commercial nuclear accident and Michigan’s closest brush with atomic disaster.

A Quiet Disaster in Michigan

In October 1966, a nuclear reactor just outside Monroe, Michigan, suffered a failure that could have changed the course of American history. Deep inside the Fermi 1 fast breeder reactor, two fuel rods began to melt after a blockage stopped coolant from flowing properly.

No explosion followed. No one evacuated. In fact, most Michiganders didn’t learn what had happened for nearly a decade.

Yet what occurred on October 5, 1966, at Fermi 1 was the first partial meltdown at a commercial nuclear reactor in U.S. history—and one of Michigan’s most overlooked brushes with catastrophe.

🏗️ The Birth of a Nuclear Experiment

ENERGY.GOV, Public domain

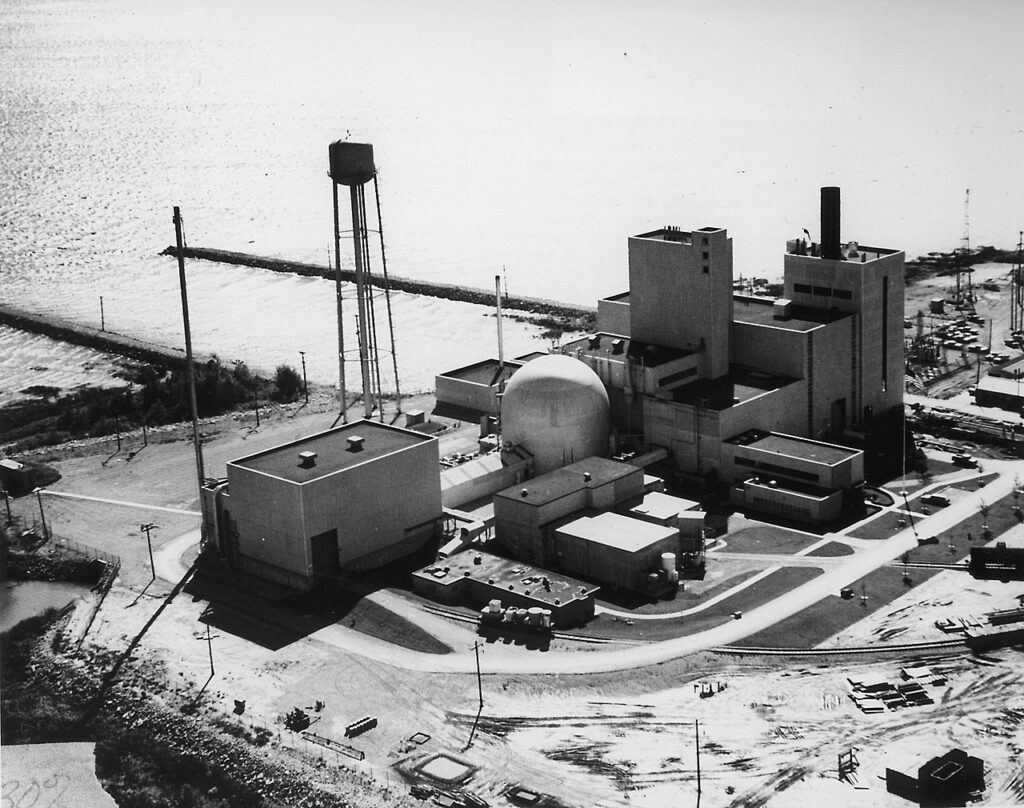

The Fermi 1 reactor was born out of Cold War optimism and the dream of limitless energy. Located along the shores of Lake Erie in Frenchtown Township, just 30 miles south of Detroit, it was a $120 million experimental fast breeder reactor funded by the Power Reactor Development Company, a consortium led by Detroit Edison.

Unlike conventional nuclear plants, which consume uranium fuel, Fermi 1 was designed to breed plutonium—a method that, in theory, could produce more fuel than it used. It was also extremely complex and unproven.

Construction began in 1956, and by 1963, Fermi 1 began limited operations. But technical issues plagued the facility. In the first ten years of its existence, it generated electricity for just 52 hours.

🔥 October 5, 1966: The Incident

At 3:09 p.m. on October 5, 1966, reactor operators noticed something wrong. Coolant flow within the reactor core had dropped sharply. The coolant—liquid sodium, a highly reactive metal—was used instead of water. It was efficient at heat transfer, but incredibly dangerous if leaked or exposed to air.

As flow rates dropped and temperatures began to spike, a shutdown was initiated. But the damage was already happening.

What engineers would later discover was a 3-by-8-inch piece of Zircaloy—a metal plate—had broken loose inside the reactor and lodged in a cooling channel. It blocked the flow of sodium coolant to part of the core. Temperatures soared to over 1,900°F, and two uranium fuel rods began to melt.

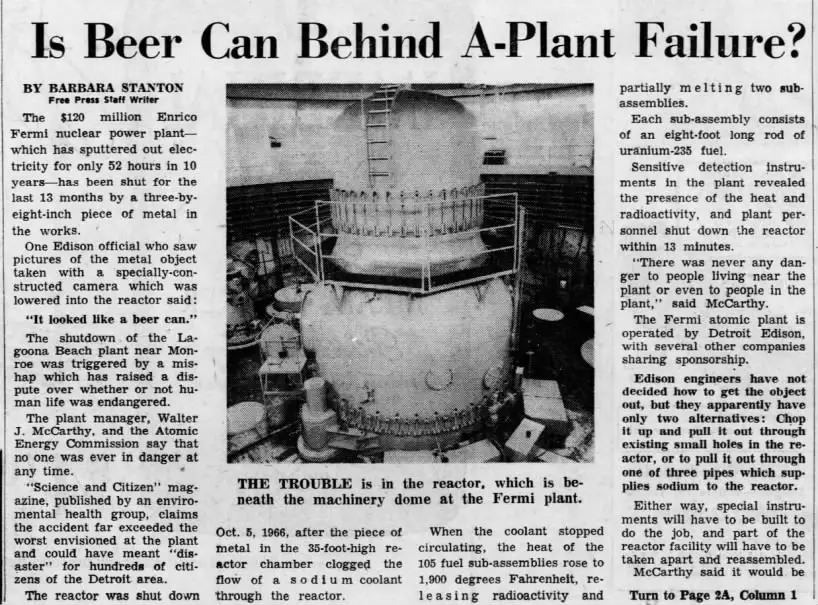

One engineer who reviewed images of the blockage described it as looking like “a beer can.” The nickname stuck—and headlines soon followed:

“Is Beer Can Behind A-Plant Failure?”

“Nuclear Plant Fails; Beer Can to Blame?”

⚠️ No Alarms, No Public Warning

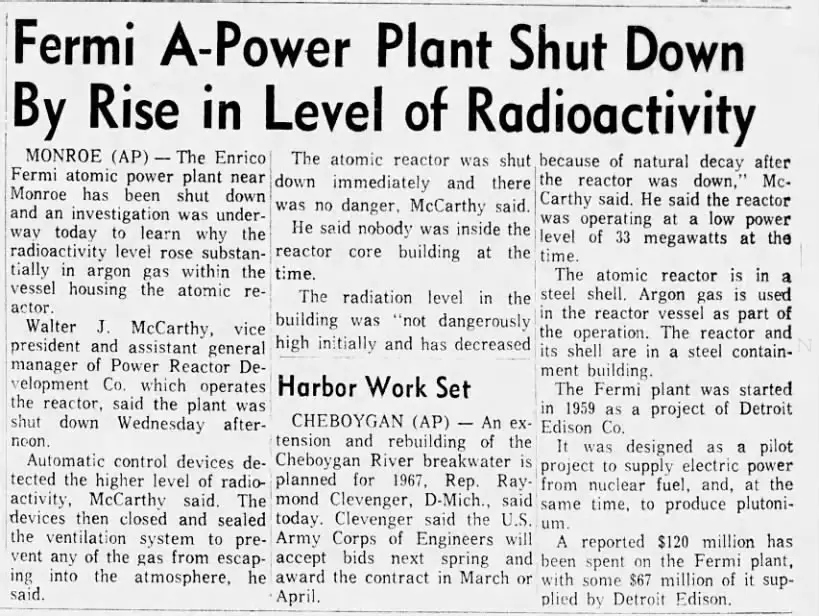

Despite the severity of the incident, there was no public alert. No sirens. No evacuation. Not even a news conference from the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which oversaw the plant.

It wasn’t until 13 months later, in late 1967, that the full scope of the damage was acknowledged. Even then, officials insisted there was no danger to the public. But independent scientists disagreed.

A report published in Science and Citizen by author Sheldon Novick argued that the incident exceeded the AEC’s so-called “maximum credible accident” scenario.

According to a 1957 AEC study, a worst-case nuclear meltdown at a reactor like Fermi 1 could result in:

- 3,400 deaths

- 43,000 injuries

- Fallout spreading across Detroit, Toledo, and southern Michigan

Novick wrote, “The huge quantities of radioactivity involved and the proximity of Detroit made such a prospect terrifying indeed.”

📚 “We Almost Lost Detroit”

Images on this page may contain affiliate links in which we may receive a commission. See our affiliate disclosure for details.

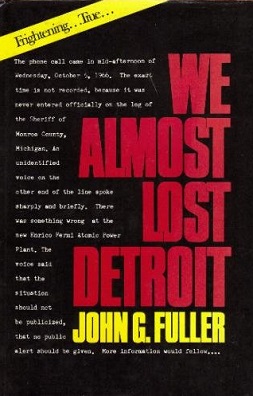

In 1975, journalist John G. Fuller published a book titled We Almost Lost Detroit, detailing the incident and the years-long effort to minimize its impact. The title was controversial—but it stuck.

Even critics who downplayed the risk admitted the event should have been handled with more transparency.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists considered it a noteworthy read, stating that it delved into the details of the accident’s occurrence without addressing the underlying reasons. Kirkus Reviews characterized it as the most severe critique of the Atomic Energy Commission in recent times.

Ultimately, the 1966 Fermi 1 nuclear incident highlights the complexities and risks inherent in nuclear power generation.

The phrase entered the public consciousness again in 1979, when Gil Scott-Heron released a haunting spoken-word song of the same name: “We Almost Lost Detroit.” The song became an anthem of nuclear skepticism and environmental awareness.

🚫 The End of Fermi 1

By 1972, Fermi 1 was permanently shut down. It had never fulfilled its promise as a fuel-generating reactor. Cleanup and containment took years. Today, the reactor building remains in place—entombed in concrete and steel, with environmental monitoring still ongoing.

Detroit Edison—now DTE Energy—eventually built a more conventional facility, Fermi 2, nearby. That plant began operations in 1988 and continues to supply electricity today.

But the fast breeder dream was buried with Fermi 1.

🧪 The Technology and the Risk

Why did Fermi 1 fail?

The fast breeder concept was ahead of its time—and poorly understood by many of the engineers operating it. Using liquid sodium as coolant introduced unique hazards. Even small design flaws could become catastrophic. The reactor had no automatic system to detect the specific blockage that caused the incident.

After the incident, a 13-month cleanup and inspection followed. The damaged uranium rods were removed. Radioactive materials were sent for study at Battelle Memorial Institute. Engineers had to choose between cutting up the lodged metal piece or pulling it out via reactor piping. Neither option was safe.

In the end, the risk proved too high, the results too modest.

🗺️ Fallout: Legacy and Reflection

Today, most people in Michigan have never heard of Fermi 1. It’s not taught in schools. There’s no historical marker on I-75. But for those who lived in Monroe, or followed the Cold War energy race, it remains a sobering example of how close the nation came to disaster—without even knowing it.

We didn’t lose Detroit. But we came close enough to write the book title.

🔍 Sources

- Detroit Free Press, November 1967

- Science and Citizen, June–July 1967

- We Almost Lost Detroit by John G. Fuller (1975)

- U.S. Atomic Energy Commission archives

- DTE Energy public records