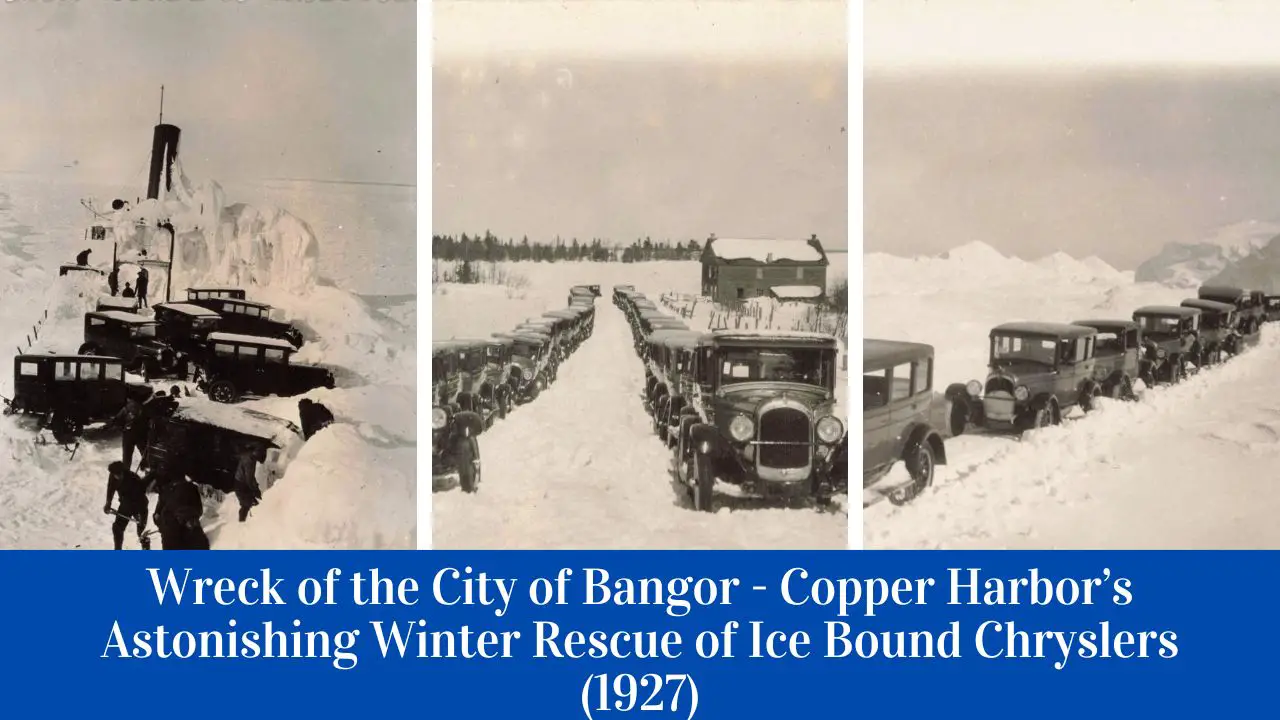

On a brutal night—November 30, 1926—a 445-foot freighter named City of Bangor lost the fight against a Lake Superior blizzard and piled onto the rocky north shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula, east of Copper Harbor. In her steel belly sat a shipment of brand-new cars: hundreds of 1927 Chrysler sedans bound from Detroit to Duluth. By dawn, the crew was shivering onshore and the freighter was sheathed in ice, its cargo sealed inside a floating freezer.

Video – The Ship Wreck of the City of Bangor and Its Cargo of 1927 Chrysler’s

The City of Bangor Cargo counts vary—and that’s part of the story

Period reports and later histories don’t agree on the exact number of automobiles aboard. Totals range from about 220 to 248, with most sources citing 248 vehicles, “mostly Chryslers” and a handful of Whippets. What is clear: 18 cars lashed on deck went into the lake during the storm; the rest stayed dry in the hold behind a watertight bulkhead.

A hard march and a rare “double rescue”

Captain William J. Mackin and his crew of roughly 29 men launched lifeboats after the seas fell. Aiming for Copper Harbor—likely 12–15 miles away over deep snow—they started walking and got turned around in the dark. The following day, the U.S. Coast Guard lifeboat from the Eagle Harbor Life-Saving Station, skippered by Capt. Anthony “Tony” Glaza, happened upon them after first ferrying the crew of the steamer Thomas Maytham, which had grounded on the opposite side of the peninsula the same night. It was an uncommon two-for-one save in the same storm. Several Bangor sailors were treated for frostbite.

How do you unload cars from a frozen ship? You build an ice road.

Through December and January the wreck sat encased in rime. When Superior locked up solid, salvors carved a ramp of ice and snow from the freighter’s side to the shore. Mechanics warmed engines, checked fluids, and—one by one—drove the cars off the ship and along the packed lakeshore toward Copper Harbor. In late winter and spring, once roads reopened, the cars went by road to Calumet, then by rail to Detroit for repairs and resale. Contemporary tallies say 202 vehicles ultimately made it out.

The Upper Peninsula meets Motor City

Photographs from February 1927 show neat rows of fresh Chryslers parked in snowdrifts like a pop-up dealership in the woods. The images feel almost staged, yet they were a practical step in a complicated salvage that linked Michigan’s two identities—maritime and automotive—in one scene. The Keweenaw’s shoreline, forests, and heavy lake-effect snow made the job slow; the cars were effectively stored in a natural freezer until crews could move them.

What became of the City of Bangor?

Declared a total loss, the freighter was left to the elements. Portions were later cut up for scrap, and the site today lies within the Keweenaw Underwater Preserve, a popular target for advanced divers when conditions allow. The ship’s story didn’t end underwater, though. One of the salvaged 1927 Chryslers stayed in the area and is now displayed at the Eagle Harbor Lighthouse Museum complex, which also tells the saga of the rescue and salvage.

Why the numbers never quite match

If you read around, you’ll see “about 248 cars,” “roughly 220,” or “202 saved.” The spread likely comes from a mix of shipping manifests, newspaper summaries, and later retellings that rounded figures. Wartime scrapping and the remote setting also mean fewer surviving records. For readers who like clean totals, that’s unsatisfying; for historians, it’s a reminder to treat tidy numbers from chaotic events with care.

A ship built in Bay City, a cargo made in Detroit

The City of Bangor was built in 1896 at Bay City and converted from an ore carrier to an automobile hauler the year of the wreck. Its cargo, assembled in Detroit, was en route to midwestern dealers who were hungry for the latest models despite a tightening winter shipping window. That timetable—late-season navigation on Superior—set the stage for the mishap.

Plan a visit

- Eagle Harbor Lighthouse & Museum (Keweenaw County Historical Society): See a 1927 Chrysler tied to the wreck’s story and period photos; hours vary by season.

- Keweenaw Underwater Preserve: Experienced divers can view what remains of the Bangor along with nearby wrecks. Charter operators in the U.P. monitor conditions, which can shift quickly on Superior.

Fast facts (with caveats)

- Date of grounding: Nov. 30, 1926, near Keweenaw Point, east of Copper Harbor.

- Crew saved: All hands; several treated for exposure after an overnight slog across deep snow.

- Cars aboard: About 248 (figures vary 220–248); 18 on deck lost overboard. ~202 later salvaged.

- What happened to the cars? Driven off on an ice ramp in Feb. 1927, staged near Copper Harbor, taken to Calumet, then rail to Detroit for refurbishment and resale.

Why it still captivates

The images are unforgettable: shiny Detroit sedans idling beside snowbanks in the north woods. It’s the contrast that hooks us—new technology meeting raw weather, a modern supply chain interrupted by ice. Nearly a century later, the story still draws readers because it shows how Michiganders stitched together ingenuity and grit to finish the job, even when winter shut the door.

Editor’s note: Figures and distances above use the best available sources; where accounts differ, I’ve noted the range. For further reading, see the Detroit Free Press overview, the Lighthouse Digest article on the salvage, and the detailed Wikipedia entry with citations to period newspapers and books.