In June 1962, 59 student activists gathered at a lakeside union retreat in Port Huron, Michigan. Over five days, they wrote what would become one of the most important political manifestos of the 20th century. The result was the Port Huron Statement, which became the founding document of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

🏕️ Michigan’s Quiet Political Ground Zero

The setting was Fellowship Hall, a union-owned summer camp operated by the United Auto Workers. Located on the shores of Lake Huron, it offered a peaceful retreat from campus life—and a perfect backdrop for deep political reflection.

The group included students from the University of Michigan, Oberlin College, and other progressive campuses. Most were white, middle-class, and deeply concerned about inequality, racism, and the looming Cold War.

They didn’t come to party. They came to rewrite the role of young people in American democracy.

📜 Drafting the Port Huron Statement

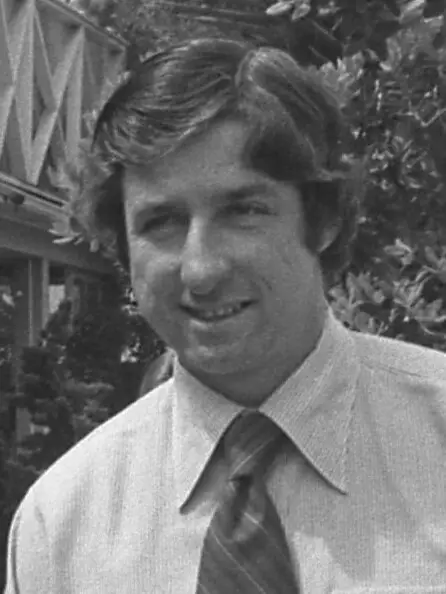

The driving force behind the Port Huron Statement was Tom Hayden, a recent University of Michigan graduate and editor of the Michigan Daily. Hayden had seen the civil rights movement up close in the South and was disillusioned with both major political parties.

What emerged was a bold, 75-page political vision. It wasn’t a list of demands—it was a moral diagnosis of American society and a blueprint for a more just and democratic future.

The opening line set the tone:

“We are the people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”

🗳️ The Vision: Participatory Democracy

At the heart of the statement was the idea of participatory democracy—the belief that people should have a direct say in decisions that affect their lives.

The document criticized the concentration of power in Washington, the military-industrial complex, the inequalities of capitalism, and the racial injustice woven into American life. It also targeted apathy and what Hayden called the “automatism of campus life.”

SDS wasn’t just calling for reform. They were calling for engagement—an active, informed citizenry that shaped institutions, not just tolerated them.

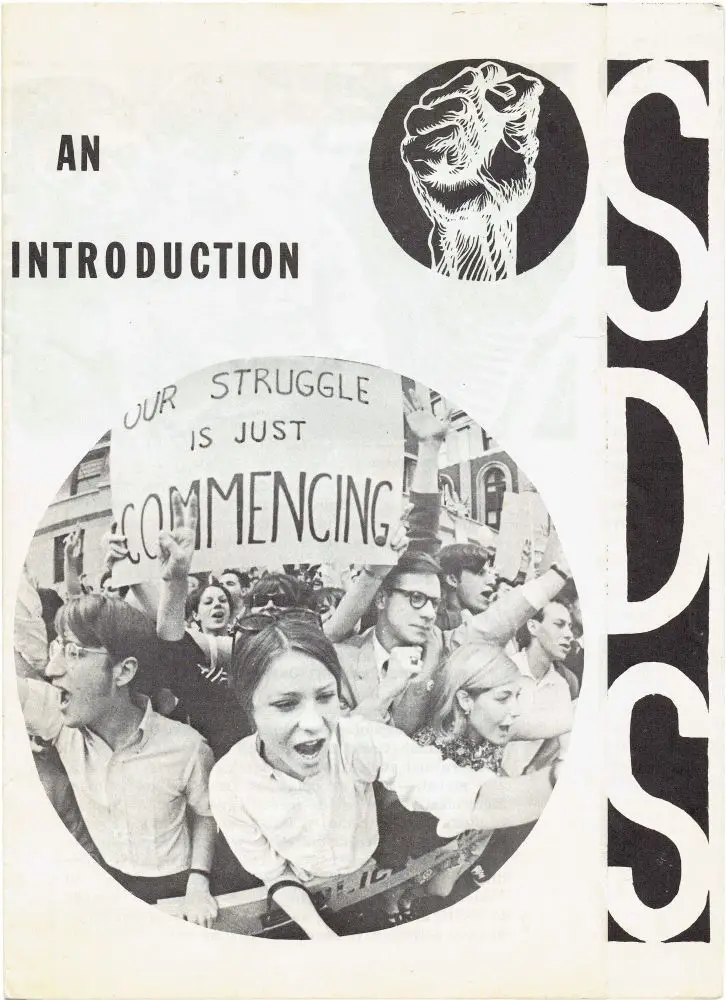

🧱 SDS Takes Shape

After the Port Huron conference, the Students for a Democratic Society gained traction quickly. From a small group of campus intellectuals, SDS grew into a national force with chapters at more than 300 universities.

Their activism spanned civil rights, voter registration drives, anti-poverty programs, and later, opposition to the Vietnam War. SDS was instrumental in organizing the first major national protest against the war in 1965 in Washington, D.C.

By 1969, SDS had over 100,000 members and had become the face of the American student left.

⚠️ The Fracturing of SDS

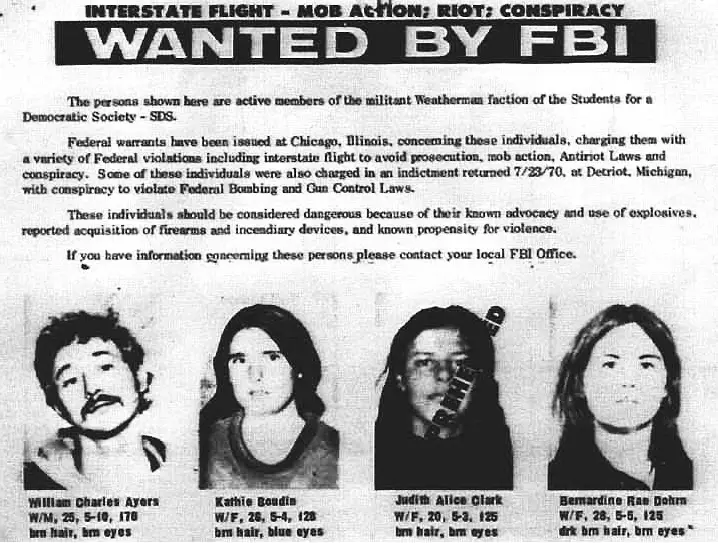

Success brought challenges. As SDS grew, it became ideologically fragmented. Some members pushed for more radical tactics, while others remained committed to nonviolence and organizing. Tensions erupted over the war, Black Power, and Marxist theory.

By the early 1970s, SDS splintered. Some members broke off to form the more militant Weather Underground. Others left politics altogether.

Despite its collapse, the Students for a Democratic Society left a lasting legacy in campus activism, political discourse, and progressive organizing.

📍 Port Huron’s Place in History

The fact that the SDS and the Port Huron Statement emerged from a summer retreat in Michigan is no accident. The state’s labor legacy, strong university culture, and progressive union ties made it fertile ground for political experimentation.

The United Auto Workers’ sponsorship of the retreat also speaks to a brief moment of alliance between labor and student activism—something that would grow increasingly rare in later decades.

Today, few know that one of the most impactful student political organizations in American history began on the edge of Lake Huron.

🔄 Why SDS Still Matters

Many of the issues raised by the Students for a Democratic Society in 1962 are still with us:

- Political disengagement

- Racial injustice

- Economic inequality

- Disillusionment with institutions

- Foreign policy contradictions

The language may have changed, but the core themes of the Port Huron Statement still resonate. Its emphasis on participatory democracy has inspired environmental movements, feminist organizing, and newer student-led actions.

In a time when youth political engagement is once again rising, the legacy of SDS remains instructive—and alive.

📝 Sources

- The Port Huron Statement, SDS, 1962

- Tom Hayden archives, University of Michigan

- The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage by Todd Gitlin

- Oral histories from SDS founders

- United Auto Workers union historical records