Before highways crisscrossed Michigan and air travel became routine, the Great Lakes were the region’s superhighway—and no name loomed larger on those inland seas than the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company. For nearly a century, its fleet of grand steamers ferried passengers between major Midwest cities, offering luxury, speed, and the romance of lake travel. With staterooms that rivaled hotels and ballrooms that echoed with live music, D&C ships weren’t just transportation—they were destinations. This is the story of how a Detroit-born company redefined travel on the Great Lakes and how its legacy endures long after the last whistle blew.

Table of Contents

Listen to the Podcast

Origins on the Great Lakes (1850–1870s)

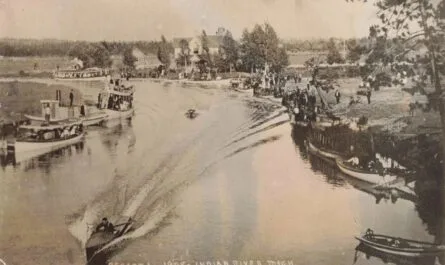

The Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company (D&C) traces its roots to the mid-19th century, when steamships were vital connectors between growing Great Lakes cities. In 1850, Captain Arthur Edwards launched the Detroit & Cleveland Steamboat Line, beginning with two modest paddle-wheel steamers—the Southerner and the Baltimore—offering overnight service between Detroit and Cleveland.

These early “boat trains” were humble compared to what followed, but they met a pressing need: carrying travelers and freight across Lake Erie in an era when railroads were still sparse. The enterprise was incorporated in 1868 as the Detroit & Cleveland Steam Navigation Company, which formalized a venture that would soon blossom into a regional institution.

Yet, growth did not come without perils. In June 1868, the steamer Morning Star, one of the company’s ships, collided with a schooner in the darkness off Lorain, Ohio, and sank with a heavy loss of life. The tragedy – which claimed at least 30 lives – underscored the dangers of Great Lakes navigation in that era.

Despite such setbacks, the D&C Line persevered. Its early captains and crews earned a reputation for grit and reliability, building passenger trust. By the 1870s, the company was poised to expand beyond its small beginnings, buoyed by the Great Lakes’ growing importance as highways of commerce and travel.

A New Captain at the Helm: James McMillan and Expansion (1870s–1900)

A turning point came in the late 1870s when Detroit industrialist James McMillan set his sights on the steamship business. About a decade after incorporation, McMillan – a railroad and shipbuilding magnate – took control of the D&C Line.

Under his leadership, the company entered a golden age of expansion. McMillan was already president of the Detroit Dry Dock Company (a major shipyard) and wielded significant influence in business and politics. His resources and vision helped transform D&C from a modest regional line into one of the Great Lakes’ premier passenger carriers. The line not only survived financial panics in 1873 and 1893, but it thrived. McMillan consolidated rival routes and upgraded the fleet, ushering in larger and more luxurious vessels.

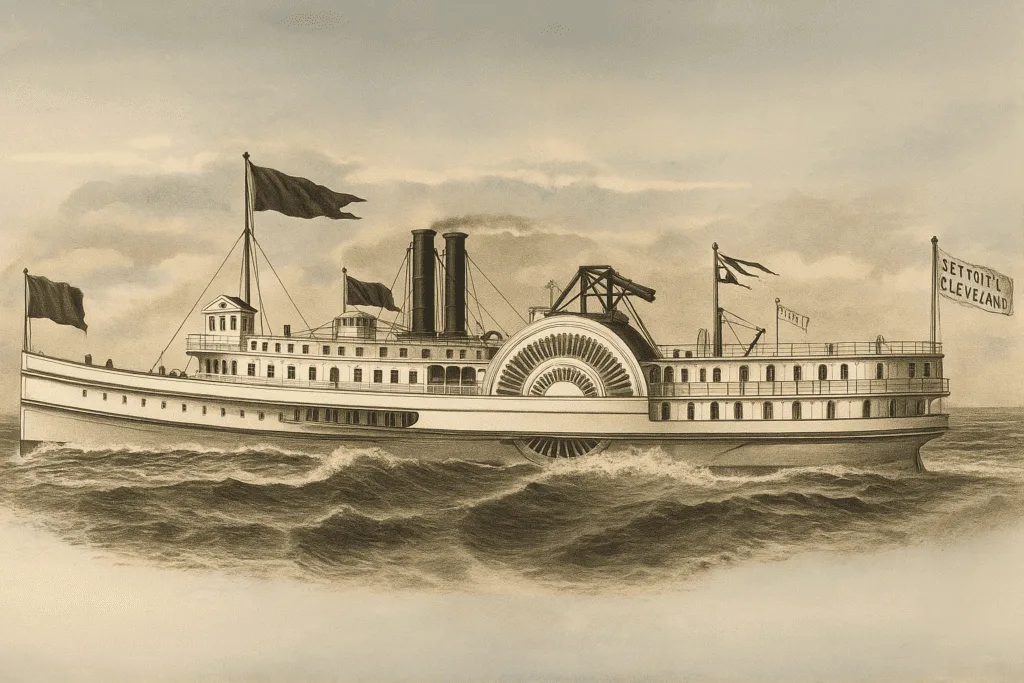

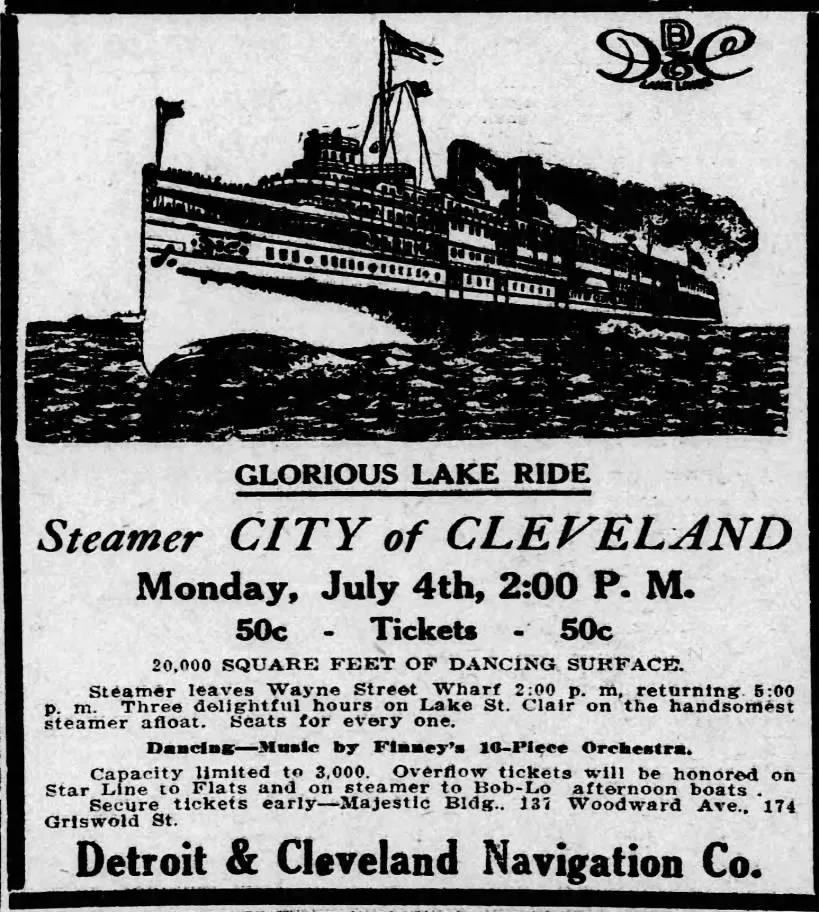

In 1878, the company launched the first City of Detroit, a steamer designed by the brilliant naval architect Frank E. Kirby. This began a naming tradition (City of Detroit, City of Cleveland, etc.) that would brand D&C’s ships as floating extensions of their home cities. By the turn of the 20th century, business was booming, and D&C had earned a reputation for excellence.

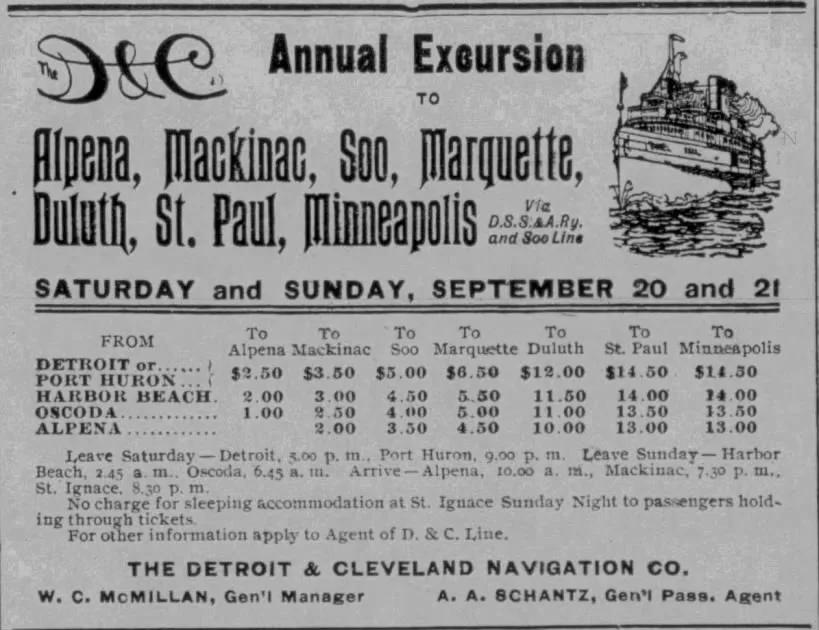

McMillan’s hand at the helm – followed by his family after he died in 1902 – ensured that D&C became synonymous with dependable service and expanding horizons. The line’s network grew to reach ports beyond Detroit and Cleveland, including Buffalo, Toledo, and Mackinac Island, reflecting Detroit’s emergence as a hub of Midwest travel.

Floating Palaces of the Great Lakes (1900–1920s).

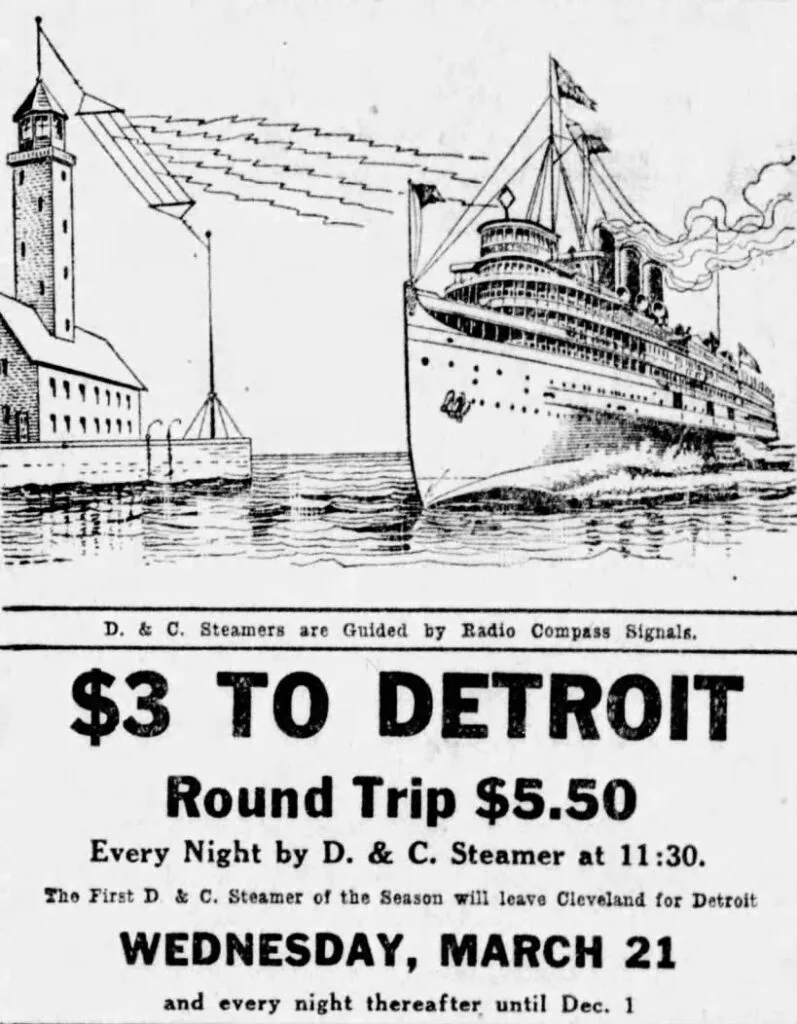

At the dawn of the 20th century, a trip on a D&C steamer was both practical transportation and a romantic adventure. In an era before jetliners and freeways, Michigan and Midwest travelers often relied on these “floating hotels” to ferry them overnight to distant cities.

Each evening from spring through fall, passengers boarded D&C’s palatial ships, enjoyed dinner and music, and then drifted to sleep in cozy staterooms – awakening the following day at their destination. The D&C Navigation Co. became famed as the greatest of the Great Lakes “night lines,” a maritime equivalent of the red-eye train.

Its vessels were soon acclaimed as “floating palaces” and even “honeymoon ships,” celebrated for their comfort and grandeur. Company brochures boasted that “no safety device, no matter how insignificant, is overlooked. No item that adds to the comfort of the passenger is neglected.” Indeed, the experience could rival ocean liners.

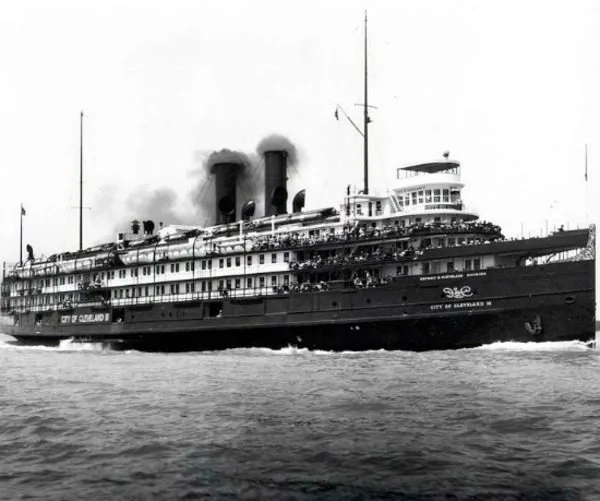

One Detroit newspaper raved in 1908 that the newest D&C steamer City of Cleveland (III) was “the most luxuriously furnished and most completely equipped passenger vessel on the lakes, not excelled in appointments or comforts by the best type of ocean-going steamers”. Travelers could stroll plush carpeted salons under crystal chandeliers, relax in lounges like the elegant Gothic Room, or promenade on the deck under the stars.

During this heyday, D&C continually outdid itself with ever-grander ships. Naval architect Frank E. Kirby – renowned as the greatest Great Lakes ship designer – was commissioned to create a new generation of steamers for the line.

In 1907, the City of Cleveland III was launched (the third to bear that name), and at 402 feet long, she was then the largest in the fleet. With her twin tall stacks and side paddle wheels, the “C-III” could carry up to 4,500 passengers (1,500 in overnight berths) and boasted interiors by designer Louis O. Keil that resembled a grand hotel.

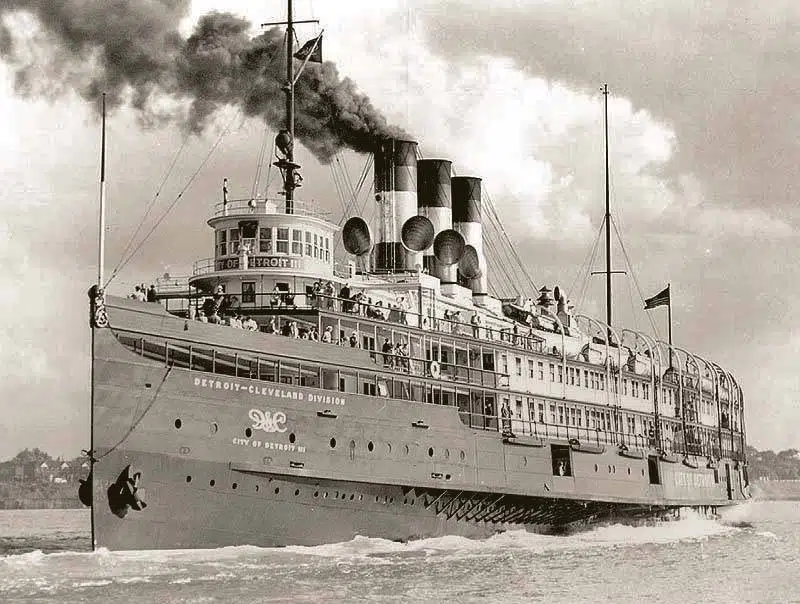

In 1912, Kirby topped this achievement a few years later with the City of Detroit III, a vessel many would call his crowning masterpiece. At roughly 500 feet from stem to stern, the City of Detroit III was “the most expensive, largest and most luxurious passenger freshwater vessel afloat at the time it was built,” as an engineering journal noted, “nothing that money could buy has been omitted” in its construction.

More than 6,000 spectators watched her launch at the Detroit Shipbuilding yard in October 1911, a spectacle of civic pride complete with mayoral and senatorial dignitaries in attendance. The City of Detroit III, with five decks of cabins, ornate wood-carved salons, and over 1,000 electric lights, truly earned the moniker “Queen of the Great Lakes.”

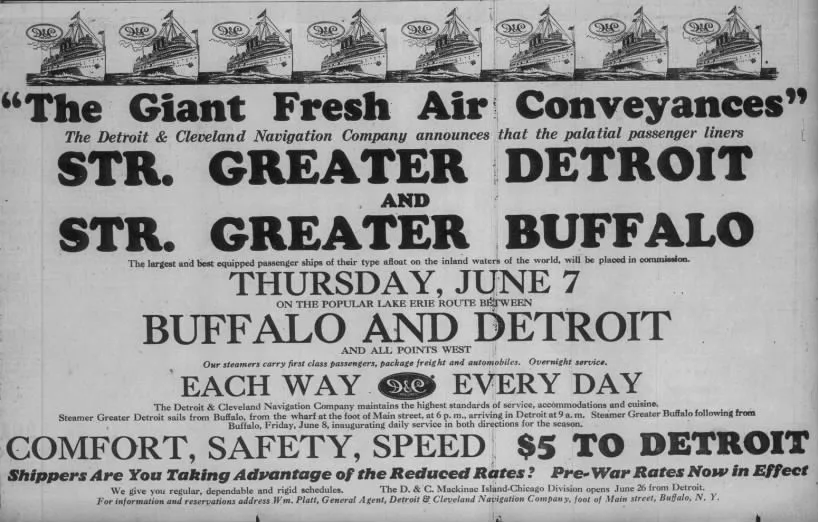

Not content with those triumphs, D&C pushed the limits of shipbuilding in the 1920s. The company’s slogan that it operated “the largest and finest fleet of side wheel steamers in the world” was no idle boast. In 1924, it introduced the Greater Detroit and Greater Buffalo, a pair of sister ships that were the world’s largest side-wheeler passenger steamers ever built up to that time.

Each stretched an astonishing 536 feet in length with a beam of 96 feet. These behemoths could carry over 2,000 passengers and even had space to ferry over a hundred automobiles in their hold – a nod to the emerging age of the motor car, with a fleet that now included the two “Greaters,” the City of Detroit III and City of Cleveland III, and the earlier twins Eastern States and Western States, the D&C Line reigned supreme on the Great Lakes by the mid-1920s.

These steamers were more than transportation: they were a defining feature of summer life in Michigan and the surrounding states.

Life Aboard the Night Boats

A voyage on a D&C night boat was an experience to savor. After the lines were cast off from the docks of Detroit or Cleveland, passengers settled in for an evening of gentle travel by water.

The ships themselves were destinations: floating resorts appointed with rich mahogany woodwork, stained-glass accents, and plush furnishings. Many featured a grand salon or ballroom where an orchestra might play tunes of the day – waltzes, rags, and fox-trots – while passengers in their finest eveningwear danced on hardwood floors.

Others preferred the simple pleasure of a stroll on the deck. Under the glow of electric deck lamps, travelers would lean against the rail to feel the cool lake breeze and watch the ship’s wake foaming under the paddle wheels. The stars above and the distant lighthouse beacons guided the way as the steamer plied through the night.

Those seeking quieter pastimes could retire to the library or writing room or find a nook on the promenade with a deck chair to read and relax. At dinner time, white-jacketed stewards served hearty meals in the dining saloon – fresh Great Lakes whitefish, roast beef, and fanciful desserts – accompanied by the clink of fine china and silver.

Such comforts led business travelers and vacationers alike to choose the boats over the train. Indeed, D&C became known for its excellent service and fine cuisine. As the night deepened, passengers retired to private staterooms, lulled to sleep by the steady thump of the engines and the lake’s rhythm. “Refreshing sleep” was a selling point; many awoke at dawn, truly rejuvenated.

Sunrise found the steamers gliding into port – the busy wharf of Cleveland, the industrial harbor of Buffalo, or the peaceful Mackinac Island dock – where travelers stepped ashore rested and charmed by the journey itself.

Trials and Tragedies on the Inland Seas

Despite the gaiety and grandeur, the D&C Line weathered its share of storms and sorrow. The unpredictable Great Lakes could turn treacherous, and even the finest crew was not immune to misfortune.

One early incident, the wreck of the Morning Star in 1868, reminded everyone of the risks inherent in maritime travel. The collision that sent the Morning Star to the bottom of Lake Erie happened in the dead of night and with little warning.

Survivors clung desperately to debris until rescued hours later by a sister ship, but dozens of lives were lost in those dark waters. Such tragedies haunted the memories of sailors and underscored the importance of ever-improving safety measures.

Over the years, D&C ships also had other close calls and mishaps. Even the majestic City of Detroit III endured a rocky start: on her first voyage in May 1912, a miscommunication in the engine room caused the brand-new leviathan to accidentally ram a smaller vessel, the Joseph C. Suit, at the Detroit dock. The little wooden freighter sank (mercifully with no loss of life), and the embarrassed crew of the City of Detroit III quickly gained a lesson in caution. The great ship went on to a long and storied career without further incident, but the tale of her minor scrape on launch day became part of D&C lore.

Fire was another constant worry on steamships: the City of Cleveland III nearly met a dire fate before ever carrying a passenger when a mysterious blaze gutted her interior during construction in 1907, leading to hurried rebuilding amid rumors of arson.

She rose from the ashes in splendid form, only to face tragedy decades later at the end of her life. On a foggy morning in June 1950 – the opening day of what would be D&C’s final season – the City of Cleveland III was struck by an upbound Norwegian freighter, the Ravnefjell, off Harbor Beach in Lake Huron.

The pleasure cruise had 89 passengers aboard (members of a Michigan chamber of commerce heading to Detroit for a baseball game) when the freighter loomed out of the mist and ripped into the steamer’s port side. In the chaos, four people lost their lives – including the police chief and a former mayor of Benton Harbor, who had been enjoying the outing.

Thanks to sturdy construction, the C-III stayed afloat and even managed to limp back to Detroit under her own power. Investigators found that her captain was at fault for sailing too fast in dense fog and too close to shore, violating safety rules. The collision of 1950 cast a somber cloud over the line’s final days. It was a bitter irony that a company known for safety and comfort met its end with a fatal accident. Yet, throughout its century of operations, the D&C Line had a strong safety record, given the millions of passengers carried.

The Twilight of Steamship Travel (1930s–1950s).

By the 1930s, the world around the D&C Line was changing rapidly. The rise of the automobile, the spread of paved highways, and the growing convenience of intercity trains and buses all began to chip away at the steamship patronage.

The Great Depression of that decade also tightened the public’s travel budgets, and the once-full pleasure cruisers saw fewer passengers. D&C continued to promote the romance of lake travel, but numbers began to fall slowly as the whims of human nature turned to new modes of transit.

Still, the company fought to adapt. During World War II, the D&C Line enjoyed an unexpected renaissance. Gasoline was rationed and long-distance driving curtailed, prompting travelers to return to the lakes. The steamers once again carried near-capacity crowds, sometimes including servicemen or war workers on the move.

One of the fleet, the Greater Buffalo, was requisitioned by the U.S. Navy and converted into a training aircraft carrier on the Great Lakes – an astonishing second life for a former cruise ship. Renamed USS Sable, she helped train naval aviators on Lake Michigan. The remaining D&C vessels maintained civilian service through the war, offering a nostalgic taste of luxury to those weary of wartime austerity.

However, when the war ended in 1945, America’s love affair with the automobile and airplane exploded. New highways and post-war prosperity meant families hit the road in their own cars or took to the skies for faster travel. The convenient overnight steamer was suddenly anachronistic to many.

By 1950, passenger bookings had plummeted to the point that only a few ships were still running, and those were often half-empty. The tragic City of Cleveland III collision in June 1950 was, in effect, the final blow to a company already on the brink.

D&C canceled the remainder of that season’s sailings, and on May 9, 1951, it formally announced the suspension of all service on the Great Lakes. After 100 years of operation, the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company quietly dissolved, ending an era. The graceful steamers that had once been the pride of Detroit’s waterfront now faced uncertain fates. One by one, the proud fleet was sold off for scrap.

The Greater Detroit, once the largest of them all, was towed to a remote spot on Lake St. Clair and deliberately burned in 1956, her charred hull later cut up for metal. The City of Detroit III and her remaining sisters were also scrapped that same year. By 1959, almost nothing was left of the D&C Line’s floating palaces except memories. It was a poignant sunset for a fleet that had once ruled the lakes – a quiet end, watching from mothball berths as the world moved on.

Legacy of the D&C Line

Though the steamers are gone, the legacy of the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company lives on in Michigan lore and maritime history. For decades, the D&C night boats had been an integral thread in the social and economic fabric of the Great Lakes region – their schedules were as reliable as the sunrise, and their whistles were a familiar sound on summer nights.

In Detroit, the memory of those “honeymoon ships” and floating excursions remains a source of regional pride. A part of the City of Detroit III survives: the ornate wood-paneled Gothic Room, where so many passengers once gathered, was salvaged before the ship’s scrapping. Its carved mahogany panels and stained-glass details were reassembled and displayed in the Dossin Great Lakes Museum on Detroit’s Belle Isle, preserving a piece of the grandeur for future generations.

The Greater Detroit’s huge bow anchor, which was cut loose and sunk during the ship’s fiery scrapping in 1956, was painstakingly recovered from the Detroit River by divers decades later; today, restored and gleaming, that 6,000-pound anchor sits outside the Detroit Wayne County Port Authority as a tangible link to the past.

Enthusiasts and historians celebrate the D&C Line’s contributions throughout the Great Lakes. Models of its ships, old company brochures, and black-and-white photographs of ladies with parasols on sunlit decks are treasured in local archives.

The company’s importance is also measured by its impact on travel patterns: it connected cities and people long before the interstate highways, fostering tourism and commerce between Michigan, Ohio, New York, and Ontario. It was one of the major passenger shipping enterprises in America’s inland waters. The story of the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company is thus preserved in artifacts and archives and the collective memory of Michigan. It endures as a story of enterprise and elegance, of summer nights on calm waters and the ceaseless progress of technology. The D&C Line became a legend. Its legacy sails on in every nostalgic tale told of the great steamers – those fabulous floating palaces that once made the Great Lakes their home.

Final Thoughts About Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company

Though the ships are long gone and their docks have quieted, the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company still sails through Michigan’s collective memory. From lavish staterooms to fog-shrouded tragedies, D&C’s history reflects the rise and fall of an era when the journey truly mattered. Artifacts like the Gothic Room and restored anchors now sit in museums, reminders of a time when Detroit’s lakefront was the starting point for grand adventures. As we look back, the legacy of D&C steamers remains a testament to Michigan’s place at the heart of Great Lakes travel—one voyage at a time.

Works Cited (MLA Format)

- Hilton, George W. The Great Lakes Car Ferries. Stanford University Press, 1962.

- Bowen, Dana Thomas. Lore of the Lakes: Told in Story and Picture. Dodd, Mead & Company, 1951.

- Barry, James P. Ships of the Great Lakes: 300 Years of Navigation. Thunder Bay Press, 1996.

- Thompson, Mark L. Steamboats & Sailors of the Great Lakes. Wayne State University Press, 1991.

- Wright, Richard J. Freshwater Whales: A History of the Passenger Steamers of the Great Lakes. Superior Publishing Company, 1969.

- United States Coast Guard. “Marine Accident Report: Collision of City of Cleveland III and SS Ravnefjell, Lake Huron, June 26, 1950.” U.S. Department of Transportation, 1951.

- Dossin Great Lakes Museum Archives. Detroit Historical Society. Accessed March 2025.

- Gannon, Michael J. “When the Sidewheelers Ruled the Lakes.” Michigan History Magazine, vol. 85, no. 2, Spring 2001, pp. 22–33.

- Cleveland Press Historical Clippings File. Cleveland Public Library, Transportation Collection.

- “City of Detroit III: Floating Palace of the Lakes.” Engineering News-Record, vol. 68, no. 12, March 1912, pp. 324–330.

- National Museum of the Great Lakes. “Greater Buffalo and USS Sable (IX-81).” Inland Seas Maritime Museum Archive, Toledo, OH.

- Department of the Navy. Naval Training on the Great Lakes: WWII Carrier Conversion Program. Bureau of Ships Historical Division, 1946.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Historical Great Lakes Navigation Data.” Great Lakes District Reports, 1890–1950.

- Michigan Bureau of Tourism. Great Lakes Cruise and Ferry Travel Guide, 1937–1950 editions.

- Detroit Free Press Archives. “Launch of the City of Detroit III Draws Thousands.” October 8, 1911.